CONVERSATION PIECE :

Soprano SHERI GREENAWALD

By Bruce Duffie

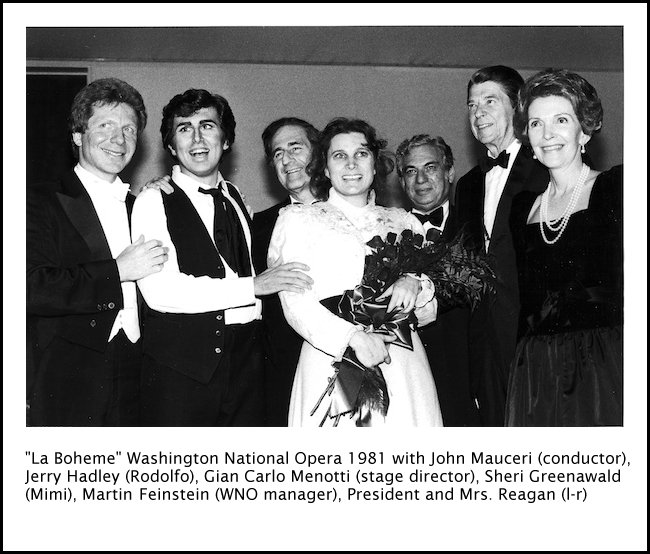

[This interview was originally published in The Opera Journal in December, 1992.

The photos, bio and links were added for this website presentation.

Names which are links refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.]

Sheri Greenawald was in Chicago in February of 1992 for appearances with

the Chicago Symphony and their presentation of the three Da Ponte operas

of Mozart led by the then-new Music Director Daniel Barenboim.

With mostly the cast which appears on the recordings, Greenawald stepped

into the role of Donna Anna in Don Giovanni.

The semi-staged performances were a triumph for all concerned, and Greenawald

would later return to Chicago for roles at Lyric Opera.

She agreed to meet with me during the CSO engagement, and we chatted a

bit about the need to set and re-set internal clocks, and the necessity of

relying on time . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie:

How much time does it take you each day to prepare for the theater and be

ready when you're going to perform?

Sheri Greenawald:

I try to eat at least two to two-and-a-half hours before curtain time.

I'm one of the few singers who eats before rather than after. I won't

go out afterwards anymore because it's so bad for your stomach and for your

weight and so on. Even if I don't go onstage right away, I still allow

that amount of time before the opera begins to build up that energy.

When I go on right at the beginning, I have to allow enough time to pace and

work up some adrenaline.

BD: At what time

do you become the character — when you step onstage,

or while the makeup is going on?

SG: I must belong to the Laurence Olivier school.

I can be talking to the stagehands two seconds before I go on, and when I

walk on the stage I'm there. Particularly if you've had a good rehearsal

period, you're so ready for that character that I can just immediately do

it when I'm out there.

SG: I must belong to the Laurence Olivier school.

I can be talking to the stagehands two seconds before I go on, and when I

walk on the stage I'm there. Particularly if you've had a good rehearsal

period, you're so ready for that character that I can just immediately do

it when I'm out there.

BD: You walk

on and switch on.

SG: That's how

I do it.

BD: Do you walk

off and switch off?

SG: Pretty much

so, but you can't switch off the adrenaline immediately. There's an

enormous amount rushing through your body even at the end, so you don't just

automatically relax. But I don't carry the character home with me.

I don't get funky if I'm doing a depressing role. I know how to act

and I just go and do it. The famous story is from the filming of Marathon Man with Dustin Hoffman and Laurnece

Olivier. Hoffman stayed up two nights in a row to look really tired

for the dental scene, and Olivier said to him, "Why don't just act my boy?"

BD: Does the

music which is always around you in an opera help you to get into each little

acting bit?

SG: Yes, particularly

in Mozart. He's such a genius that he gives it to you. You hardly

have to think about character because it's so written into the music.

Each character in each Mozart opera is set up, particularly in the recitatives.

The way he sets the words gives you the whole acting message right there.

All you have to do is physicalize it, really. That's how I feel about

Mozart, and Verdi is very much that same way as well. If you read

correctly what most composers say — the tempi and musical indications, the crescendos and diminuendos — they

really give you such an accurate character that you just need to physicalize

it. A good director will set up the framework for that action.

BD: What can

you do when you get a director that sees it differently, or tries to impose

something else upon the music?

SG: That can

get very frustrating and it's not easy to deal with.

BD: Let me turn

it around. Are there many ways of physicalizing a role correctly?

SG: Oh yes, I

think there are. They can be physicalized in many ways. Emotionally,

if someone is angry, one will slam a fist on the table, others may kick over

the wastebasket. What I mean is that the emotional drama is there in

the music, and it does leave you a palette so you can go in different directions

with it.

BD: So updatings

and strange stagings can work within those frameworks?

SG: I am all

in favor of that to a great degree, yes. With David Alden (who directed

the three Mozart operas here with the Chicago Symphony), I did a very updated

version of The Rake's Progress by

Stravinsky for the Netherlands Opera. People asked how we could do this

to an eighteenth-century story, but the composer and librettist were working

in 1950, and were affected by the events to that date including the dropping

of the atomic bomb. You can't really dismiss those things from your

subconsciousness or even your consciousness. So you can't say the music

has nothing to do with the story. I find it fun and enjoy seeing something

taken out of the old cliché settings. I like to have my imagination

piqued by new ideas. I may not agree with absolutely everything, but

I like those kinds of productions. I can certainly do traditional productions

and work within a traditional framework, but I do feel stronger when I do

something in modern dress because I feel that I don't have to worry about

movement and action. I don't have to ask if this is really an eighteenth-century

gesture. It's much more "me" then. I am more free to be me, a

1990s woman.

BD: Taking this one step further, if Stravinsky

was conscious of the dawning of the nuclear age, how can you relate the

Mozart/DaPonte/Beaumarchais Countess to today's audiences who know all of

this history which has happened since that age? Does she still speak

to us today?

SG: I think so.

The Marriage of Figaro is much more

set in its time because you're talking about the "droit de seigneur" [the "right of the

(feudal) lord" (to have sexual relations with subordinate women)], and that

sets the opera a bit more in its place than, say, Don Giovanni which is very universal.

For me, Giovanni never feels like

it's stuck in the 18th century at all. Even Così is about men and women, and

God knows we still have the fights and arguments going on today!

BD: So some operas

are easier to bring forward into today than others?

SG: I think so.

I don't mind Figaro being put into

the 20th century. It never bothers me, and in fact I'm doing Cappriccio next, and the production will

be the first time for me in the 18th century. I'm so used to doing it

in the 1920s that it will be a little bit tricky to figure out how I'm going

to play it with that sensibility.

BD: She doesn't

pick either suitor at the end, but whom does she favor?

SG: That's a

point I don't ever want to argue with a director because he may want to argue

in another direction. For me, it has a lot to do with how I feel about

the two men playing the roles. That influences me, but I do think that

Flamand's relationship with her is so much more tender and introspective,

whereas Olivier's is this passionate, constantly crashing-against-walls kind

of relationship. I always have the feeling she chooses the music in

the end, but that's just my personal sentiment. Certainly Strauss

gave no indication per se, except I think he does musically. When she

says goodbye to Flamand, she holds onto the notes as she sings them, whereas

she has sort of dismissed Olivier. The special tenderness with which

she speaks to Flamand rather than to Olivier touches me.

BD: So you have

to make sure that Flamand is not a crashing bore . . .

SG: Hopefully!

BD: In the rest of the operas in the world, where

is the balance between the music and the drama?

BD: In the rest of the operas in the world, where

is the balance between the music and the drama?

SG: With the

great composers, it's a real wedding. With Mozart, it shows particularly

in the recitatives. Mozart recitatives are some of my favorite things

in the entire world. They're incredibly ingenious, and with so many

operas it's balanced. For instance in The Rake's Progress you have W.H. Auden

doing the words, and that kind of poetry is fun to have and to sing.

But I never worry about that balance. If they're good enough, they've

taken care of it for me.

BD: Of your many

roles, is there one that might be perilously close to the real Sheri Greenawald?

SG: Are there

any crazy enough? [Laughs] When I sing the Countess in Cappriccio, I must confess I feel very

at home with her. I like her humor. I think I'm a somewhat diplomatic

human being, and I try not to ruffle too many peoples' feathers. She's

very good at keeping people in their place and calming them down. I

like her a lot. I can't say that I'm really her, but I feel very comfortable

with her. When I did Natasha in War

and Peace, I understood that character's passion. When I was

young, I was very much like Natasha. I was ready to elope and jump out

windows and take poison and all of that. I felt a deep compassion for

that character as well, and the way Natasha evolves in the book

— becoming a nursing mother as I have been. We all would

like to be Natasha in a way. She's one of the great heroines of all

time.

BD: Now you bring

up the fact that you have a family. How do you balance the career with

the demands of being wife and mother?

SG: Well, it's

sort of unbalanced at the moment in that my daughter travels with me.

She starts school next year so then I'm going to have to figure out how to

balance it. To date it's sort of built-in.

BD: Does she

like flitting all over the globe with you?

SG: She's had

a good time seeing zoos in every part of the world.

BD: Do you like

flitting all over the world?

SG: It's getting

less and less fun, I must say. The glamor wears off very quickly, and

if I never saw a suitcase again it would be too soon. But, it's part

of my job, and you're lucky if you get to go places often. I hope I

can come back to Chicago again. I've spent there and a half months here,

and I really like Chicago. It's a great city. I'm a Midwesterner

myself, and I feel very at home here.

BD: Where is

home now?

SG: Home is in

France in a small village southwest of Paris. I go to Seattle often

and spend a lot of time in Santa Fe at the festival there. So it's nice

when you go back to familiar places. You don't feel so away-from-home

always.

* *

* * *

BD: Let's talk

of some French roles. Tell me about Massenet.

SG: People tend

to downgrade him, but if you examine his scores there's as much detail as

in Puccini. I've sung Manon

and Cendrillon, and they're really

interesting scores to learn. I've really enjoyed them. He's

a wonderful composer, very colorful, and the orchestrations are exciting.

He's much neglected, actually. He's in and out of fashion, and he

is not being done at the moment.

BD: Is it especially

difficult to do him in France?

SG: I did Manon

in Nice and also in San Francisco, which is where I did Cendrillon. They say the French

like music except for French music, but it's interesting because you have

the immediate contact via the language without using the surtitle-bridge.

I only did one performance in Nice. Neil Rosenshein was

the Des Grieux, and we had a huge success that night. I enjoyed it

a lot, and the audience really got into it. But that's the south of

France, so it's like being in Italy in a sense. In Europe I work in

European-size houses, which are a lot smaller than the ones in the U.S.,

so the relationship to the audience is more palpable. You can really

feel the audience in a much stronger way. It's not that you don't feel

them here in the bigger houses, but it's something that you're more aware

of. The acting that I do is sometimes very subtle, and it's easier

for me to do my preferred kind of work in a smaller house where people are

going to see a much smaller gesture or an eye-movement. When you're

in a big house, you really have to adjust your acting style a bit.

Small movements aren't going to carry, and they can't really read an expression

in your eyes.

SG: I did Manon

in Nice and also in San Francisco, which is where I did Cendrillon. They say the French

like music except for French music, but it's interesting because you have

the immediate contact via the language without using the surtitle-bridge.

I only did one performance in Nice. Neil Rosenshein was

the Des Grieux, and we had a huge success that night. I enjoyed it

a lot, and the audience really got into it. But that's the south of

France, so it's like being in Italy in a sense. In Europe I work in

European-size houses, which are a lot smaller than the ones in the U.S.,

so the relationship to the audience is more palpable. You can really

feel the audience in a much stronger way. It's not that you don't feel

them here in the bigger houses, but it's something that you're more aware

of. The acting that I do is sometimes very subtle, and it's easier

for me to do my preferred kind of work in a smaller house where people are

going to see a much smaller gesture or an eye-movement. When you're

in a big house, you really have to adjust your acting style a bit.

Small movements aren't going to carry, and they can't really read an expression

in your eyes.

BD: So you adjust

your stage-deportment. Do you also adjust your vocal technique? [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at left, see my interview with Arleen Augér.]

SG: You can sing

much softer in a smaller house. You can't afford to in a big one.

You can also sing off into the wings in small house, but in a big one you

need to sing downstage half the time. The requisites are different.

BD: Are the audiences

different from country to country or city to city?

SG: [Laughs]

Oh yes. I immediately think of the Parisians who can be just vicious.

I have heard them boo people within an inch of their life, and it's frightening.

American audiences are quite polite. They may not be real warm to

you if you've sung badly, but they won't usually boo. I have been very

lucky, knock on wood. I've never had the experience personally of being

booed in France. I had to step in at the last minute to do Gluck's Armide in Paris at the Chatelet.

They were expecting Montserrat Caballé, so let me tell you, I was

nervous that night. But it went very well, thank you Gods of Music.

BD: Were they

rooting for you, or putting you on trial?

SG: They were

judgmental in the first act, but they can be intensely warm after they've

embraced you, and that is what happened to me.

BD: Are they

as critical about pronunciation of the French as we've been told?

SG: I live in

France now and I speak it fairly decently, so I don't know. I've not

had that experience. Perhaps if the singer was really mangling the

words...

BD: Is it better

to sing in the original languages rather than translate?

SG: It's easier

to sing because the composers have set those particular words on those particular

notes. I complain about the surtitles especially in comedy because the

laughs will come at the wrong times, often before we've played out the joke.

BD: Some singers

have told me they hear one laugh for the surtitle, and another when the action

happens.

SG: Perhaps if

it's a visual joke, but not if it's a word-joke. So that can be frustrating.

But I understand how much the surtitles bring to the audience, letting them

be simultaneously involved rather than just in a general way. I see

both sides of the coin, but I am always grateful when I can sing in the

original language.

BD: One last

bit of Massenet. You've sung Cendrillon,

so how is that different because people are perhaps more used to seeing Rossini's

Cenerentola?

SG: It's set

so differently, and the music so far afield. The Massenet is more like

the fairy-tale in a strange way, and it's more romantic because the music

was written so much later. When I did it, we had a beautiful carriage

and the whole bit, so that helps.

BD: Do you particularly

enjoy singing title-characters?

SG: I'd rather

do that than not. Which singer doesn't? [Laughs]

BD: Have you

sung any evil characters?

SG: I'd be real

good at them!

BD: Really?

[With a smile while moving away just a bit] Why?

SG: Oh they're

fun to act. I would love to do the title role in Blitzstein's Regina, but that's for a more dramatic

and mezzo-ish voice than mine. Maybe when I'm an old lady I'll try

to do it. And the Governess in Britten's Turn of the Screw (which I've done) wreaks

havoc on the evening and brings everything to the fore. She's fun to

play and I enjoy doing her a lot, but mostly I get to play heroines.

BD: Are most

of your parts victims?

SG: Well, that's

the whole thing of opera. We all have to die, I guess. Opera is

about sex and death. Mimì is certainly a victim in La Bohème. I have a director-friend

who wants to stage Traviata with

Violetta tied in a chair for the whole evening. I can understand that

idea because she is a victim of everything including her health and society

and everything.

BD: Would that

make Alfredo or Germont sado-masochistic?

SG: Well, they

are in a strange way.

BD: So is opera

really true to life?

SG: It should

be.

BD: [With a bit

of sadness] That doesn't speak very well for us, then.

SG: Let's face

it, the human race is not all sweetness and light. That's why a really

good opera can translate into modern language because of the kinds of foibles

that go on. Figaro is a good

example. A lot of men are not faithful to their wives in this day

and age, so the kinds of pranks that went on in the 18th century are going

on in the 20th.

BD: You've done

some world premieres. Are they particularly rewarding because you can

help to shape them?

SG: They're fun

to do, and I've always enjoyed them. You don't always get to shape them

as much as people might think. I did the world premiere of Bernstein's

A Quiet Place, and I remember Lenny

calling me up and saying, "How high do you want to sing?" I said, "No

higher than a D," so he did stick a high D in once. So I guess it's

my fault that the note is in there, but that's the amount of shaping or molding

I was able to do on that piece.

BD: Does that

give any other soprano license to alter that note, knowing it was written

for you?

SG: That was

the standard practice for years and years. Singers would always change

notes to accommodate themselves. A long time ago, people changed whole

keys for arias, and that goes on today, though people may not be as aware

of it. Most roles were written with someone in mind. Mozart had

a certain soprano in mind when he wrote Constanze and the Queen of the Night,

and we're cursing him still!

BD: Do you have any advice for composers who want

to write operas as we hurtle toward the next millennium?

BD: Do you have any advice for composers who want

to write operas as we hurtle toward the next millennium?

SG: They have

to be able to set conversation to music, and yet I still like to have something

that's lyrical. I sang Cordelia in Lear by Aribert Reimann, and

for all the atonality of it, it was very lyrical — my

part particularly. I really enjoy that, but I don't care if it's atonal

or whatever. If you can maintain a lyrical line for the singer and

keep in mind that the voice functions best in a lyrical manner, that would

be the advice I would give, and I would hope that the composer would respect

that.

BD: Do many respect

that these days? [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right,

see my interview with Ashley

Putnam.]

SG: Oh yes, I

think they do. It would be really difficult to be an opera composer

in this day and age. Which tree are they going to bark up? My

friend Thomas Pasatieri writes in a lyric, late-romantic style, and his works

get killed because the critics say it's nothing new. Others write

very new music and are told it's unlistenable.

BD: So what's

a composer to do?

SG: Tear their

hair out, I guess. Just follow your muse. Do what you feel you

have to do. Tom cannot write anything but the music he writes, so why

should he try to be something he's not? Write from your heart.

Whatever speaks to you, that you must do.

BD: Where is

opera going these days?

SG: I hope it's

not going into a museum. That's another reason I appreciate directors

who take chances and do things that are a little out of the ordinary.

That production of The Rake's Progress

that I spoke of had the usual Netherlands Opera crowd the first night, but

then word got out that this was a special production. We had everything

from motorbikes to cars to dwarfs doing handstands. Baba the Turk is

from the circus, remember, so here she comes with her entourage. By

the end of the run, I would look out at the audience and see punk clothing

and hairstyles. When I would sing the lullaby to Tom at the end, he

was in a straightjacket and was lying across my lap, and I would see many

in the audience crying. I don't know how many productions of this work

leave people in tears, but this one certainly did. So, obviously, it

really was working, and that is the best. Keep in mind that people are

used to seeing rock videos and situation comedies. We are inundated

with images and information, so the opera must keep people's imagination,

and that's difficult because of this competition.

BD: Should the

opera producers try to attract the audience that usually watches rock videos?

SG: Why not?

Why shouldn't we? We're entertainers, and the minute you forget that,

you're in big trouble. Mozart was the Andrew Lloyd-Webber of his time.

Why should we put it in formaldehyde like it's going to wither and lose

its color and become something dead?

BD: Was Mozart

the Andrew Lloyd-Webber of his time or the Madonna or the Michael Jackson

of his time?

SG: There's not

too much difference as far as I'm concerned. They're popular entertainers

attracting a wide crowd, and we're competing with that.

BD: Are we winning?

SG: I don't know

if we're winning, but we have to put up the good fight.

BD: Are we at

least holding up our end of it?

SG: In many cases

we are. Some of us are certainly trying. We're out there dancin'

and singin' and tryin' our best.

BD: Are you optimistic

about the future of opera?

SG: I try to be and I hope to be. I'd like

my profession to go on for a few more years, but the music is so great that

I don't think we have to panic. I can use my daughter as a gauge, and

she watches rock videos sometimes, but she also watches Nick Jr., and Walt

Disney animation. She also watches A&E, and she loves to watch ballet.

There was a new version of Swan Lake,

and she watched it from beginning to end. I don't think she would have

stayed with it if it had been totally traditional. The images of people

in modern dress spoke to her more readily. She also comes to the operas

I'm in, and often starts to sing along, and she sings to me in the style

of the work when we're at home. So this week, with the three Mozart

works at Orchestra Hall, the tunes she's making up for me are very Mozartean.

So, I guess, yes, we can win.

SG: I try to be and I hope to be. I'd like

my profession to go on for a few more years, but the music is so great that

I don't think we have to panic. I can use my daughter as a gauge, and

she watches rock videos sometimes, but she also watches Nick Jr., and Walt

Disney animation. She also watches A&E, and she loves to watch ballet.

There was a new version of Swan Lake,

and she watched it from beginning to end. I don't think she would have

stayed with it if it had been totally traditional. The images of people

in modern dress spoke to her more readily. She also comes to the operas

I'm in, and often starts to sing along, and she sings to me in the style

of the work when we're at home. So this week, with the three Mozart

works at Orchestra Hall, the tunes she's making up for me are very Mozartean.

So, I guess, yes, we can win.

BD: Should we

take a straight Mozart work and make it in the rock video style?

SG: You mean

a film of an opera? I don't care for films of operas because I can

always tell that people are lip-synching. That really irritates me.

I can't deal with it because I know it's not real. But if you could

make the film and simultaneously record the sound, I'd go for it. A

staged work in a film atmosphere would be very good. Why not try it

and see what it means, ultimately. If it's meaningful, why not?

If it's not meaningful, it won't be successful. I'm in the business

of recreating. I'm not a creator, so we have to try things.

BD: When you

are recreating, how do you decide which roles you'll work on and which you'll

let go?

SG: That's fairly

easy because the voice has a certain range and certain possibilities.

You automatically fall into a category, or a fach. I'm falling into the Strauss/Mozart

fach because that's what my voice

is most suited for, and that's where I'm most comfortable. But I don't

want to limit myself to those parts. I'm dying to do Ellen Orford in

Peter Grimes because I love that

opera. I say I'm going to sing Strauss, but I won't do Salome because it's too heavy and demands

too much sound. That's one of the problems of this media-age

— we're getting so used to canned performances, and I like live

ones. TV is canned, and CDs are canned.

BD: Even some

of the "live" rock concerts now are really canned.

SG: The good

ones are still live. I think that exposing the problem was one of the

greatest things. It was good to

take back the grammy award from Milli-Vanilli. However, the other

side says here were two guys who looked great paired with two guys who could

sing, and since rock videos are all lip-synched anyway, why not make the

package? I don't think it was scandalous except when the two lookers

were expected to sing. They should have been honest about what was

going on. Audrey Hepburn didn't sing in the movie of My Fair Lady. Does that mean her

performance was any less good?

BD: But how many

people know it was Marni

Nixon singing?

SG: I knew, but

I was aware of that.

BD: Do you like

being booked two or three years in advance?

SG: Sometimes,

sometimes not. I have to think how old my daughter will be when these

contracts are dated, and it's confusing and frustrating sometimes. When

I consider a job, I have to consider her as well. I turned down a lot

of offers during the time she was starting school because I wanted to be

there. It's a big adjustment for her, and I didn't want to be gone

then.

BD: Do you take

your husband into consideration, also?

SG: My husband

is an agent, so he understands these things. It's often his fault that

I'm gone, anyway! Thank goodness he's very considerate and accommodating.

I've often thought how difficult it would be to have someone who didn't understand

all the exigencies of my life.

=======

======= =======

======= =======

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

-- --

======= =======

======= =======

=======

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago in February of 1992.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1997. This transcription was made

and published in The Opera Journal

in December of 1992. It was slightly revised, the photos, links and

the bio were added and it was posted on this website in 2015.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website,

click here.

To read my thoughts on

editing these interviews for print, as well

as a few other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce

Duffie was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in

Chicago from 1975 until its final

moment as a classical station in

February of 2001. His interviews have

also appeared in various magazines and

journals since 1980, and he now continues his

broadcast series on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You

are invited to visit his website for more

information about his

work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a full list of

his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information

about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field

more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

SG: I must belong to the Laurence Olivier school.

I can be talking to the stagehands two seconds before I go on, and when I

walk on the stage I'm there. Particularly if you've had a good rehearsal

period, you're so ready for that character that I can just immediately do

it when I'm out there.

SG: I must belong to the Laurence Olivier school.

I can be talking to the stagehands two seconds before I go on, and when I

walk on the stage I'm there. Particularly if you've had a good rehearsal

period, you're so ready for that character that I can just immediately do

it when I'm out there.

BD: In the rest of the operas in the world, where

is the balance between the music and the drama?

BD: In the rest of the operas in the world, where

is the balance between the music and the drama? SG: I did Manon

in Nice and also in San Francisco, which is where I did Cendrillon. They say the French

like music except for French music, but it's interesting because you have

the immediate contact via the language without using the surtitle-bridge.

I only did one performance in Nice. Neil Rosenshein was

the Des Grieux, and we had a huge success that night. I enjoyed it

a lot, and the audience really got into it. But that's the south of

France, so it's like being in Italy in a sense. In Europe I work in

European-size houses, which are a lot smaller than the ones in the U.S.,

so the relationship to the audience is more palpable. You can really

feel the audience in a much stronger way. It's not that you don't feel

them here in the bigger houses, but it's something that you're more aware

of. The acting that I do is sometimes very subtle, and it's easier

for me to do my preferred kind of work in a smaller house where people are

going to see a much smaller gesture or an eye-movement. When you're

in a big house, you really have to adjust your acting style a bit.

Small movements aren't going to carry, and they can't really read an expression

in your eyes.

SG: I did Manon

in Nice and also in San Francisco, which is where I did Cendrillon. They say the French

like music except for French music, but it's interesting because you have

the immediate contact via the language without using the surtitle-bridge.

I only did one performance in Nice. Neil Rosenshein was

the Des Grieux, and we had a huge success that night. I enjoyed it

a lot, and the audience really got into it. But that's the south of

France, so it's like being in Italy in a sense. In Europe I work in

European-size houses, which are a lot smaller than the ones in the U.S.,

so the relationship to the audience is more palpable. You can really

feel the audience in a much stronger way. It's not that you don't feel

them here in the bigger houses, but it's something that you're more aware

of. The acting that I do is sometimes very subtle, and it's easier

for me to do my preferred kind of work in a smaller house where people are

going to see a much smaller gesture or an eye-movement. When you're

in a big house, you really have to adjust your acting style a bit.

Small movements aren't going to carry, and they can't really read an expression

in your eyes. BD: Do you have any advice for composers who want

to write operas as we hurtle toward the next millennium?

BD: Do you have any advice for composers who want

to write operas as we hurtle toward the next millennium? SG: I try to be and I hope to be. I'd like

my profession to go on for a few more years, but the music is so great that

I don't think we have to panic. I can use my daughter as a gauge, and

she watches rock videos sometimes, but she also watches Nick Jr., and Walt

Disney animation. She also watches A&E, and she loves to watch ballet.

There was a new version of Swan Lake,

and she watched it from beginning to end. I don't think she would have

stayed with it if it had been totally traditional. The images of people

in modern dress spoke to her more readily. She also comes to the operas

I'm in, and often starts to sing along, and she sings to me in the style

of the work when we're at home. So this week, with the three Mozart

works at Orchestra Hall, the tunes she's making up for me are very Mozartean.

So, I guess, yes, we can win.

SG: I try to be and I hope to be. I'd like

my profession to go on for a few more years, but the music is so great that

I don't think we have to panic. I can use my daughter as a gauge, and

she watches rock videos sometimes, but she also watches Nick Jr., and Walt

Disney animation. She also watches A&E, and she loves to watch ballet.

There was a new version of Swan Lake,

and she watched it from beginning to end. I don't think she would have

stayed with it if it had been totally traditional. The images of people

in modern dress spoke to her more readily. She also comes to the operas

I'm in, and often starts to sing along, and she sings to me in the style

of the work when we're at home. So this week, with the three Mozart

works at Orchestra Hall, the tunes she's making up for me are very Mozartean.

So, I guess, yes, we can win.