Thomas Gilbert

Property Master,

Lyric Opera of Chicago (1973-2011)

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

The Civic Opera House in Chicago, shown from the North end, which

The Civic Opera House in Chicago, shown from the North end, which

is the Stage Door (rather than the Patron Entrance, which is at the

South end).

Notice the columns, which make up a special part of a story told in

this interview.

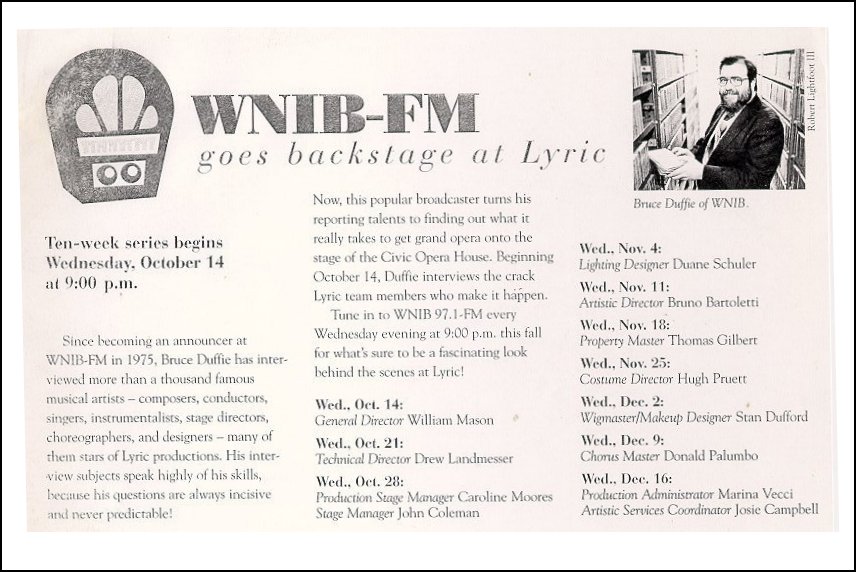

As can be seen from the image below, there was a special series

on WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago, devoted to the backstage personnel

of Lyric Opera of Chicago. This ten-week series ran at the end of

1998, and was repeated at the beginning of 1999. Each program had

portions of one of my interviews, and music that went along with the discussion.

The sixth program featured the Property Master Thomas Gilbert.

We met on the last day of July of 1998. At the time, he was

in the midst of a thirty-eight-year career with the company. Being

there for such a length of time, he saw things from the perspective

of the old, almost original stage-configuration, as well as the newly-renovated

space.

The photos included on this webpage have been selected to show

props as much as possible.

Though not used to public speaking, my guest quickly became comfortable,

and talked knowingly about his specific area. He recounted problems

that arose, as well as hilarious details from his memory.

As we were setting up to record, Gilbert was thinking of unusual

things to tell me . . . . .

Thomas Gilbert: One time, we needed eighty

chairs in the pit for the chorus. I think it was the Poe opera

[The Voyage of Edgar Allen Poe by Dominick Argento.] So,

we covered them all in black. They were the only chairs we

could get from what we had, so we didn’t have to buy any.

Bruce Duffie: [Settling in for the

conversation] What is your title?

Gilbert: Prop Master of Lyric Opera

of Chicago.

BD: How long have you been in that

position?

Gilbert: This is my fifth year as

the Prop Master. Before that, for about fifteen years I was

the Small Prop Man.

BD: What’s the job of Small Prop

Man?

Gilbert: The Small Prop Man does

most of the running around. I was doing rehearsals, and I did

most of the shopping for props, and all the little things everyone

needed, and some of the big things, too.

BD: The Prop Master then oversees

that?

Gilbert: He oversees the whole crew,

the whole operation, the staging, all the props on the sets, and

the changeovers, and loading in and loading out, bringing shows in,

taking shows out.

BD: What exactly is a prop man?

BD: What exactly is a prop man?

Gilbert: There are different kinds

of props. There are the small props, which are defined hand

props. This means everything they handle on the set. It

varies from baskets, to dish ware, to real food. If they want

real food, we cook it.

BD: Is a sword a prop, or is that

a part of the costume? [See image at left.]

Gilbert: A sword is a prop. It’s

considered an armor, and there is a different person for that. There

is an Armory Man here who takes care of all the armory, including

the guns and that kind of thing.

BD: Does that come under your jurisdiction,

or is it away from your department?

Gilbert: He’s separate. He

is by himself, although he is considered part of the crew, but he

really isn’t. We help him if he needs help. Sometimes

he has huge shows, with all the spear carriers, and he needs more help.

But he has the Federal Firearms License, so he can get the guns

when we need them. He’s responsible for the live ammunition,

or live blanks when there is assigned firing on stage. [See

image of Tosca firing-squad farther down on this webpage.]

BD: He’s responsible to make sure

that they work?

Gilbert: Right.

BD: Are you responsible to make sure

that props work, or are they just simply there to be handled?

Gilbert: I’m responsible to make

sure they work.

BD: What kinds of props have to work?

Gilbert: It could be anything. A

simple suitcase has to open and close. Sometimes they find

old things they like, and if they don’t work, we have to make them work.

A suitcase, or something as simple as an old writing desk. A

lot of times we have to find things, but most of the time we’ve had

to build it from the design from a designer. He tells us what

he wants in it, and that type of thing.

BD: You build it, and maybe age it?

Gilbert: Yes. Sometimes they

want things like quills to write. Then, you put some kind of

a ballpoint pen inside the quill and make that work for them. Sometimes

they have insisted it has to write, even when no one can really see

if it works or not.

BD: How much do you have to be aware

of the person in the very back row of the top gallery with the huge

binoculars that can count the hairs on the guy’s chest?

Gilbert: We don’t really worry about

that too much, because the people up in the back balcony can see

a lot of stuff that most of the people don’t see in the theater. They

sometimes can see over the sets, and they see us crawling around in

there.

BD: [Somewhat surprised] It’s

not your responsibility to cover that?

Gilbert: Our real responsibility

is to take care of what the singer and the director and the designer

want. That’s what’s important. Our job becomes mostly

pleasing the singers, because they’re there the whole time.

BD: If you give them a basket to

carry, and they don’t like the basket, you’d go out and buy a new

basket?

Gilbert: Yes, or if the singer doesn’t

like the knife... I remember one show and one particular singer.

We spent two and a half weeks trying to find the right bread

knife for her. We bought ten or twelve different bread knives before

we finally settled on one she would accept, because she had to cut the

bread on stage. She was just not happy with anything because she

was afraid she was going to cut herself. So it had to be preset just

perfectly. The head of the bread had to be already precut halfway

and ready to go, and the knife had to be set in a certain spot exactly

the way she needed it. There are some singers that are like that.

They are Method Singers, and they can’t sing unless the Bible is a

real Bible instead of a book just covered in black with a cross on it.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] And

then open to the right verse?

Gilbert: Exactly. [Both laugh]

BD: Before each performance starts,

do you have to make sure that every piece is in the right place?

Gilbert: Yes. Before we go to dinner

at 5:30 or 6:00 o’clock, we make sure everything is there, and it’s

already checked in. We then check it again a half hour before

the show starts. That is the time to catch anything we missed,

and it’s the time that anything that can’t be done beforehand is made

ready... for instance, real food, or something they may want to drink,

such as water or something that looks like wine. It is always prepared

at that time.

BD: Do you ever have a caterer bring in real

food?

BD: Do you ever have a caterer bring in real

food?

Gilbert: No, but we have, an occasion,

gone out to a restaurant to get the dinner instead of cooking it ourselves.

We’ve had shows which needed whole roast chickens, so we

just go and buy it at the store already made.

BD: Do you have to account for each

plate and each knife from the banquet?

Gilbert: Yes, and we wash them in

the dishwasher. Everything has to be washed in the dishwasher

according to the AGMA contracts for the singers and chorus members.

BD: Oh, it’s going to be real food

and...?

Gilbert: Everything they use

— the silverware, dishes, and especially

the glasses — has to be done in

a dishwasher. [Notice all the glasses in the photo at right. That

image is for sale by a commercial company, hence their watermark.]

BD: Even if it’s just for looks?

Gilbert: No, not if it’s only for

looks. But if they really drink out of it, or eat with it, it

does have to be cleaned in a dishwasher.

BD: What are some of the oddest props

you’ve had to deal with or get?

Gilbert: Right now, in fact, I was

out shopping most of today trying to find forty-three chandeliers

for Ariadne.

BD: Forty-three huge chandeliers???

Gilbert: Different sizes. Some

of them were maybe twelve inches by twelve inches.

BD: Do you go to Elizabeth’s

Fancy Lighting Emporium, or do you go to Joe’s Junk Shop?

Gilbert: We’re doing all antique shopping.

The designer is insisting it has to be antiques, it can’t

be reproductions. He’s got a certain style in mind. They’re

in the like late 1880’s in brass, in a little pear-shape design.

He comes in next week, so that will be a little easier. We’ve

got twenty-nine out of the forty-three so far, but it’s a tedious process.

We call it ‘shopping’,

but what we do is take pictures to send him in New York. He looks

at them, sends back his acceptance or rejection, and then I can go

buy the ones he likes. So, every round is a two-day trip to do

that.

BD: What if one of the one accepts

has been sold?

Gilbert: That’s happened, too. So

we just continue back and forth. For the Poe opera, I had to

spend a day looking for a CO2 bottle. It was a modern

one, but in the old style like a seltzer bottle. It was for the

blood effect. She was supposed to explode inside the glass case.

He wasn’t happy with everything they tried

to do with makeup and little blood bags and stuff, so we finally got

a full quart bottle. We put a mixture of real blood and water

in there, and charged it with carbon dioxide. We had to make

up a whole set of hoses for the girl that had to fit under her costume.

Then we had to connect them with hydraulic quick-connects, so that we

could connect it to her, and when she rolled out, she just had to step

on a little modified gas pedal that was mounted on the floor. She

had a full quart of blood sprayed instantly all over the inside of the

plastic.

BD: I remember that it worked very

well.

Gilbert: It worked incredibly well.

It was one of the best things I’ve ever done. I think

I had only twenty-two hours to do that. It was before the final

dress rehearsal. I had to build it and show it to him before the

dress rehearsal. It was after an orchestra rehearsal of that show.

Then we had the changeover for another show that night. Then

we came in the next day to change it over again to be ready for the

dress rehearsal. It was quite an exciting day, especially when

we tried to test it in the morning. I had everything ready to

go, and I showed it to the Technical Director so he could see how it would

work. I tried to overcharge it, and when we just touched it, it

sprayed all over the inside of the prop room and everybody that was in

it. [Both laugh] There we about six people watching. That

was about ten years ago, and there’s still blood on the wall which

they haven’t been able to get rid of yet. It was quite a sight.

At that time I was Small Props, and the Prop Manager refused to

come in the room for four days after that. He was so mad at me.

BD: It must have looked like a massacre.

Gilbert: It did. It looked

just like it.

* * *

* *

BD: Does each opera require its own

set of props?

Gilbert: Yes.

BD: Do the props then go with the sets

and costumes to the next place, or to a warehouse, or can you use

the bowl and silver chalice from one show in another show?

Gilbert: Generally, we

do re-use things. We try to keep them in stock, but it depends

on the show because some shows are ours, and some shows are rented.

Even a rented show is supposed to be complete, but invariably

the director comes in and changes everything, or there’s a few things

he wants to do special that we have to adapt to. Then we try, and

if we have to buy things, we keep them and put them in our stock. Or

we take them out of our stock to use. We do try and keep our shows

together if we can. We pack the shows, and we inventory everything.

My big thing that I’ve been working on since I became the Head

Prop Man is to get everything on computer. I’ve been able to do a

lot, and we’re getting pretty close. We’re probably 75% on our way

there. Then, with the shows that we take to go to our warehouse, they

sit there, and then, if I need something, I know what it is and where it

is.

BD: Then you borrow it?

BD: Then you borrow it?

Gilbert: I borrow it from the show.

BD: Then, does it stay with the new

show, or go back the old show?

Gilbert: It usually goes back.

BD: Is there a note with that new

show saying that you borrowed an item from another show?

Gilbert: Yes, but it depends. Some

of these newer shows we’ve done as part of the Twentieth Century

Project during the last decade we haven’t kept. We’ve thrown

them out, so some of those props I have taken put back into the stock.

BD: You salvage what you can, and

then throw away the rest?

Gilbert: Yes. I try to keep

everything possible. Even when we’re shopping and we buy something

that doesn’t work out, I save all my mistakes. That’s different

from movie prop men. I’ve talked with people who do props for

movies, and they’ll buy twelve or fifteen items for something, and when

the director decides on the one he wants, they take the others back.

But we always keep everything, and we put it in stock so someday

we’ll use it.

BD: Where is all this material stored?

Gilbert: Most of it is at the warehouse.

The large props are there, and all those small props that are part

of those shows are all stored out there. Here in the Opera House,

the sixth floor used to be full with all of that stuff, but it has been

cleaned out during the renovation. I try to keep more room open

now to use for storage space for current shows during the season. So

most of the small props are here in the building.

BD: Is there ever a time when you’re

shopping for one prop and you see something in the store that you

think would be a good prop sometime, eventually, maybe, perhaps?

Gilbert: [Laughs] Yes.

BD: Do you pick it up?

Gilbert: Oh yes, definitely.

Just last year, I was shopping for one show, buying a table for

Amistad, and it was taking so long for them to find the right

person to do the tax-exempt paperwork, that I bought four canes while

I was waiting. Then, just last week, the designer picked all

those canes to put in the Mephistopheles production because he

wasn’t happy with the ones that San Francisco sent with the show. So,

we’re going to put those canes in our show.

BD: But the San Francisco canes will

go back when the show goes back?

Gilbert: Yes, and I’ll keep mine.

BD: Is there ever a little subterfuge,

where you keep the better one and send them the other one?

Gilbert: Occasionally. [Both

laugh] I’ve been known to keep a few things, and I think they

have, too.

BD: Then this is why you’re making

your inventory on your computer, so that you won’t lose a ladle?

Gilbert: Yes, something like that, but

more stuff like paper props such as letters and documents and things

like that. Sometimes they send some really nice stuff, and I will

keep a few of them. Then I will make copies and send back the

rest because that’s a little harder to do. You need the right

person to do that kind of thing. There’s not many people who do

the old script, and some of the designers want it to look authentic, even

though no one in the audience can see it. You can get away with

a lot here because we’re so far from the audience.

BD: Do you want the public to know

and appreciate the props, or do you want to just be part of the

action that produces a great show?

Gilbert: It should be both, really.

The designers want everything usually to be perfect, but they are not

standing out in the front row looking at it. They come up on

stage, and stand there looking at things. I’ve had a designer tell

me that a piece of paper doesn’t feel right. [Laughs] I

told him that he wanted yellow paper, and that was yellow paper. Sometimes

it is a little bit aggravating because it’s over the top. It’s

more than it needs to be. Some singers insist on having the paper

with what they are singing written on the letter, or having what the

letter is supposed to say. They want it written on there.

That’s when someone has to go get it out of the book, and give it to me

so we can write it down.

Gilbert: It should be both, really.

The designers want everything usually to be perfect, but they are not

standing out in the front row looking at it. They come up on

stage, and stand there looking at things. I’ve had a designer tell

me that a piece of paper doesn’t feel right. [Laughs] I

told him that he wanted yellow paper, and that was yellow paper. Sometimes

it is a little bit aggravating because it’s over the top. It’s

more than it needs to be. Some singers insist on having the paper

with what they are singing written on the letter, or having what the

letter is supposed to say. They want it written on there.

That’s when someone has to go get it out of the book, and give it to me

so we can write it down.

BD: Are there any props that are

destroyed routinely — letters

or papers that are torn up as part of the action?

Gilbert: Yes.

BD: If there are eight shows, then

do you have to have ten or twelve of them ready to go?

Gilbert: Yes, usually a couple dozen

by the time they get through the rehearsals. The rehearsal periods

are a worse time for props because the singers break them. As

soon as they get bored, and they sit there, they take their prop and

they’ll go into the corner and play with it. They’ll be hitting

something with their cane, and break the cane. Fans are notorious.

I handed one singer a fan one day, and as she walked out to the

wing to go on for her entrance, she broke it before she went on stage.

BD: What happened?

Gilbert: She just started flipping

it. I don’t remember exactly, but she just started flipping

it and flipping it, and it cracked and was broken. She handed

it to me and said, “I need it in one minute. Can you fix it?”

[Both laugh]

BD: What did you say to her at that

moment?

Gilbert: You try. Sometimes

you take a little piece of tape, and you tape it together. That

time it was one fold smaller. You fold it over, put a piece of

tape on it, and then later you try to glue it that way and make it right.

Fans are the worst. Glasses, of course, get dropped all

the time and broken, as do dishes. However, the most spectacular

breakages are mine.

BD: Really???

Gilbert: Oh, sure. I’ve dropped

a tray of glasses. The first time I had the dishwasher, I had

dozens of champagne glasses to wash. I was trying to figure out

how to get all those glasses in there, so the first time I did it I

put about eighteen of them in. Then I ran the cycle, and when

they came out, I only had six whole ones left. [Laughs] That’s

how I learned my lesson. You can only do a few at a time. It

may take ten loads, but it’s only during tech week that you might have

to do it overnight and do it again. Once the show starts, you usually

have three or four days between shows, so it’s not a problem. It is

just during the tech weeks that it gets to be a little bit of a problem.

* * *

* *

BD: Are you at all concerned with the

music? Does the music influence you in your selection of props,

or is that completely dictated to you by the director or the designer?

Gilbert: Those decisions are mostly

from the designer, the director, and the singers. The music

doesn’t come into that. The singers probably decide the most,

because the designers and directors go away after opening night, and

I have to live with the singers for seven or eight more shows.

BD: Is that good or bad?

Gilbert: I have just learned that’s

the way it goes. On numerous occasions, after the director

goes the thing changes because sometimes the director and the singer

argue, and I’m in the middle. You’re trying to please the singer,

but the director doesn’t want you to do that, or the designer doesn’t

like that, so they insist it has to be this way. But then, when

they’re gone, the singer says, “Now, I want it that way.” It happens

every time we do a show with incense in it. They want incense. They

want to see it and they want to smell it. They want to see the smoke,

and, of course, the singers start objecting right away. Inevitably,

for the second show it’s gone as soon as director is gone. [With

a grin] I guess, we shouldn’t tell them that, though. [Both

laugh]

BD: You’re

giving away trade secrets!

Gilbert: Yes.

BD: [Following up, like a seasoned

reporter...] What else shouldn’t we know? [Laughs]

Gilbert: There’s not too much. There’s

a few little things, but you don’t like to tell everybody all your

secrets...

BD: Is running properties a fun and

satisfying thing to do?

Gilbert: It’s challenging. It’s

always different, and that’s what I like about it. You may

like or not like the director or the designer, but it’s always challenging.

The hardest part is to please them. It can be really, really

hard. It can sometimes be a painful experience, especially that

last week, tech week, when we are all working and getting everything

right. There’s not many shows like that, but you get through them.

You really feel satisfied when you get it done, and the guy is

happy and he thanks you. He shakes your hand after the opening night,

and goes away happy.

BD: Is it harder to get

it up and running the first time, or to keep it running for ten or

twelve shows?

Gilbert: It’s harder the first time.

Once you get through that, things ease up a bit. Changes

inevitably occur during that last week, through the last to dress

and orchestra rehearsals. They are the hardest.

BD: You’re the Property Manager now

for the company, so you do all eight productions?

Gilbert: Right.

BD: Have you worked in the same capacity

for theater as well as opera?

Gilbert: Yes. In Chicago, I’ve

done everything in theater. It’s been about thirty years since

I started working when I was sixteen. My first day in the theater,

I worked Sweet Charity at Shubert Theatre.

BD: Doing what?

Gilbert: I was on the rail pulling

the rope. So, I’ve done everything. During my time I’ve

been a carpenter, I’ve been the soundman, the electrician.

I’ve done repertory shows. I spent twelve summers in between

opera seasons out at Poplar Creek Music Theatre. I’ve done everything,

including industrials, operas, ballets, the whole thing.

BD: Then you’re the right man to

ask this question. From your point of view, how is opera different

or the same from a rock show, or from an industrial show, or from

a musical or a straight play?

Gilbert: It’s harder... at least here

at Lyric, it’s harder because everything is in repertory.

BD: That means more than one show

is running at the same time?

Gilbert: Right, and it’s constantly

changing. Designers and directors get upset that you can spend

twenty-four hours a day working on their show, but at the same time

I’m working on their show, I’m working on two other upcoming shows,

and I’ve got maybe two more shows running. So, there’s probably

three shows switching around on stage, and one or two more in rehearsal

in the rooms upstairs. You’ve got everything going, and everything

is in the air. They get upset when they have to have this tomorrow,

and you tell them they can’t. We just don’t have time to do it by

tomorrow.

BD: They’ll have it the following

day?

Gilbert: Maybe the following day, maybe

tomorrow. It has to be right, and we do the best we can, but

there’s a point where we have to stop and change over to do a show

that night. There’s only so much time every day you can spend

on each production. That’s the hardest part. Everything

else you do outside of this one you’re working. Your whole focus

is to do that show that night.

BD: In the end, though, does it all

get done?

Gilbert: Oh yes, eventually.

BD: You’ve never missed a deadline,

or failed to get a prop?

Gilbert: I think there’s only one time...

It was the first time we did the Ponnelle production of Don

Giovanni here. It was something about the food on the table

at the end. He wanted shrimp, and he came up with these ideas,

but the singers kept objecting. He wanted me to get real shrimp

and shellac it, because they were complaining about the smell. It

was a whole two-week period of going through every idea I came up with.

It just didn’t work out. The other big thing was that he wanted

them to throw a cup, but didn’t want it to break or shatter. I finally

came up with some pewter cups. He wanted it bigger and bigger,

but I just I couldn’t find anything bigger. We finally had to settle

with that smaller one, but overall he was very happy with everything else.

It eventually came down to what we probably should have done in the

first place. There was a long period of time I spent looking and

looking and looking, and ultimately I just wasn’t able to satisfy him.

So, we had to settle for what worked for the singers.

* * *

* *

BD: Coming back to these new chandeliers,

are you given a certain budget, and you have to stay within that budget,

or do you just go and buy chandeliers?

Gilbert: No, they established a budget.

I don’t know what the top number is, but they set a target

of $350 per chandelier. Most of them have been coming under that,

but I think we’re getting to point where we’re going to have to look

at how much I have spent so far, and figure out how much we have left.

Then, maybe we will spend a little more on some of the chandeliers

to get some bigger ones to give them a more varied look, because we’ve

gotten a lot of small ones and we got a few big ones. But the three-foot

spreads he probably would like to see are just not cheap. You can’t

find them for under $500, and even then they’re pretty hard to find.

Then, the flyman isn’t too happy about that anyway, because all these have

to go up in air during the show. It’s got to work, because everything

else is working.

BD: Are you supposed to try to come

in under budget?

Gilbert: Yes.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Do

you get a bonus if you beat the budget?

Gilbert: [Sadly] There are no bonuses.

[Both laugh] This budget is pretty strict. Most

of the time I usually don’t work with the budget. It usually

comes down to a matter of making them happy. I go out and look,

or my assistant goes out and looks, and then we come back and say these

are options, these are pictures, this is going to be this, this is this

much. Then, I sit down and talk about it, and it goes all the

way up. They say, okay, yes or no, and you eventually either go back

and get that, or you have to settle for something else... or we go down

into the shop. We have a couple of pretty good carpenters downstairs

that can whip out in a day or two what you need and make it look aged.

For instance, last year in Amistad, we were trying to find

two tables for the two sets of lawyers in the trial scene. They had

to sit on little pallets that could only be so big, and they had to be

pushed out with push sticks, and ride in the tracks. So, they had

to be a certain size, and the certain style that he wanted. We couldn’t

find it, and we didn’t have much time, so we made them. We went through

a book with the designer, and he picked out what he wanted to see. We

took that down with the dimensions we had to have, and the carpenters made

it. The next day we brought in the scenic artist to paint it the way

he wanted, and he was very happy. So were we, because it worked!

In the end, it didn’t cost nearly as much as a real antique table

that size.

BD: Are there times when you are

asked for an antique, and you give them a reproduction that looks

just as good?

Gilbert: Yes, because sometimes the

whole process of going back and forth of what we want to spend, and

what you want to do sometimes hits a stone wall a little bit. It

becomes a little war of wills of who’s going to win. Then it gets

down to the end, and there’s no time to complete it. When you get

to the last ten days, sometimes there’s just not time to go out and do

the shopping, to spend the time looking. For a chandelier, we’re

in the middle of the summer now, and I can steal a day every week, or

two days every week to go looking. But during the season, when

you’re doing changeovers and shows, that’s a lot harder to do.

BD: When you’re still down ten chandeliers,

can they go without ten chandeliers?

BD: When you’re still down ten chandeliers,

can they go without ten chandeliers?

Gilbert: Yes, or they’ll say we’re going

to go get those over there, and that will be it. We’ll get that,

and we’ll live with that, because there comes a time when we’re going

to put these together, and the electricians and the carpenters have to

make all of these work. They have got to figure out how they’re

going to hang them. He wants three in each line hanging from a

single electric line, and he wants little black socks. So, until

they make all the decisions about where everything is going to hang,

it is a process. We can’t sew the socks until the cables are made,

and it is decided exactly how he likes it. The electricians have

got to get the cables, get the right lengths and then finish it all up.

BD: Being Ariadne, is all this

for the Prologue, or the Opera?

Gilbert: I’m not sure. I’ve

seen the drawings, and we look at them, but I never paid attention

to what scene they’re in. It doesn’t matter to me. I just

have to work and get it for them.

BD: It really doesn’t matter where

they are, just that they are there at the right time?

Gilbert: Right.

BD: Do you ever make a suggestion for

the use a prop here, or tell them you’ve got something in the warehouse

that can be used there?

Gilbert: Yes, we do that all the

time. We have a pretty good picture catalog of our props

— all the chairs, tables, and stuff

that we let them look through. If that fails, then we bring out

all our research books and look through them. They say what they’d

really like, but they’ll settle for this. Then you go out and

try and satisfy them.

BD: What’s the biggest prop you’ve

ever had?

Gilbert: The biggest prop we have is probably

the Buddha last year, the one for the Pearl Fishers. It’s

about 20 some feet long. [Shown at left are photos of the

skeletal structure (above), and the finished item (below).]

BD: That’s a prop, not part of the

scenic design?

Gilbert: Yes. We consider that a

prop, and it’s still in a truck because we don’t know what we’re going

to do with it when we get to the warehouse. They made it one piece,

instead of smaller pieces to put together. I don’t think we can

get it in the elevator to get it upstairs where we’d like, because we

try to keep the first floor of the warehouse clear for the sets. Those

are the hardest things to handle, the heaviest things, and you don’t

want to be taking that stuff upstairs. You can’t take this piece

which is so big, so I don’t know what we’re going to do with it. So,

it’s still sitting in a truck. I think that’s the biggest prop,

along with big statues.

BD: Do you remember The Love for

Three Oranges?

Gilbert: Yes.

BD: Do you still have the ladle for

the Cook?

Gilbert: No, they threw that out

during the renovation, along with the rest of those sets. That

was part of the auction for the Opera Center. We cleaned up the

third floor of the warehouse because no one knew what was in there.

There were two rooms as you got off the elevator on the third

floor, and you looked down and some of it was cleared out. We

had some stuff there, but you look back down that room and then the next

room, this is two hundred feet long and twenty-six feet high, and all

you can see is crates. It looked like the ending shot from Raiders

of the Lost Ark, and no one knew what was in that stuff.

BD: There were no labels???

Gilbert: There were labels, but a

lot of them were empty. Some of them had stuff inside, and some

didn’t.

BD: Maybe your predecessor liberated things

for other productions?

Gilbert: It might have been that,

or maybe there was never anything in there since the time they stored

them there. Those crates were leftover from the original

Chicago Opera Companies which used to do a lot traveling back in

the early 1900s. [Most of the years and destinations are enumerated

in my articles on Massenet

and Wagner by the Chicago

Opera Companies before Lyric (1910-1946).] So, we went through

all of that stuff and found some antiques, and some really nice antique

furniture we didn’t know we had.

BD: Did you save all that?

Gilbert: Yes, we saved all that.

We found a complete set of the original production of Three

Oranges. The carpenter knew it when he saw it because

he was here then. It was all huge, huge furniture, way oversized,

and it’s all orange. There was lots of stuff like that. Of

the stuff we didn’t throw out, we donated a lot of it to the auction.

I don’t know how well that went, but there were some pretty unwieldy

pieces in that Oranges show, like all those big Plexiglas bubbles

that go in little valleys and roll all over the stage, and those three

oranges that open with the peels. There was a lot of big stuff,

like the Cook’s ladle you asked about. He

was on a dolly. It was a big hoop-skirt steel frame with wheels.

He got in it, and then they put the skirt around them and wheeled

them all over the stage. It was pretty funny.

BD: Oh, it was a great scene.

BD: Oh, it was a great scene.

Gilbert: That was a fun opera.

I liked that a lot.

BD: What’s the smallest prop you

have?

Gilbert: I’ve been dealing with earrings.

BD: [Surprised] That’s not considered

part of the costume?

Gilbert: Sometimes it is, but sometimes

they use them as props instead of wearing them. I get a lot

of costume props, too, and I wind up having to take care of that stuff.

I’ve had earrings, glitter, coins...

BD: Will the director tell you exactly

how much money the character’s supposed to have in his hand?

Gilbert: Yes, and a deck of cards

has to be exactly a certain way, with the ace of spades on top, and then

the deck has to deal out exactly this way. [The famous poker

scene in La Fanciulla del West was significant enough to be used

on a poster, as seen at right. Her ‘winning’

hand (after sneaking cards from her stocking) is three aces and a pair.]

BD: So, you have to fix it up and

make sure it all works?

Gilbert: Yes.

BD: I assume you wouldn’t trade this

job for anything.

Gilbert: No. It’s a lot of fun. Sometimes

it’s very aggravating, but it’s a good job.

It’s always different, and that’s what I like. It’s not

a 9:00 to 5:00 job.

* * *

* *

BD: How long have you been with the company

in some capacity?

Gilbert: This is my twenty-fifth year.

I started in 1973 right after I finished college. I came

in to work the first season as an electrician. I took a year

off to try to get a job in the real world, and then I decided that wasn’t

too good an idea. I came back to Lyric and worked three years

as a carpenter. I was switching to props when the job for Small

Prop Man opened up. That was in 1978, and I’ve been here ever

since.

BD: I hope you’re here for many more

years.

Gilbert: I hope so, too.

BD: Thank you for the conversation. It’s

fascinating getting to talk to the people back stage who are actually

making the show work.

Gilbert: It’s more interesting, sometimes.

I’ve often said it’s a better show backstage,

watching us change the sets, or do the scene changes. [Laughs]

They should sell tickets to that.

BD: Should the public really be aware

of how difficult it is to run a show?

Gilbert: I think they would appreciate seeing

how some changes are made, especially something like La Bohème.

The change from Act One to Act Two we do as a pause now [instead

of a full intermission]. In five minutes we change from the

interior Garrett to the outdoor of Café Momus. It is

a pretty amazing change.

BD: What about the snow in Act Three

[shown below]. Is that the props department?

Gilbert: We fill the bag, and we

sweep it up. The carpenters run the pipes to make it work,

because that’s in the fly system. So, it’s kind of a mixture.

When they screw up and dump it on the floor, we have to clean

it up. We have a lot of those prop-sets. We have a snow drop,

a paper drop, a confetti drop, and the streamer drop. There is

all kinds of stuff coming out of the sky in that show, and they’re

all in different scenes. The streamers are in the parade, and

the paper drop is the end of the act. The snow is in the next act.

BD: Speaking of snow

— this time real snow — you

mentioned having to store sets outside of the building.

BD: Speaking of snow

— this time real snow — you

mentioned having to store sets outside of the building.

Gilbert: Yes, on Washington Boulevard

and on Wacker Drive in between the pillars. We hid them. Sometimes

during the changeovers [between afternoon rehearsals and evening performances],

we would take all the pieces out and fill up the spaces between

the pillars before the rush hour. The people going to the train

station were coming by to go home. Then, the next day we would

change them back before the rush hour. We’d bring them all back

in again.

BD: You said earlier that some of

them were starting to move???

Gilbert: During the blizzard we had

that problem. I think the production was Capuleti. The

scenery was all covered with tarps, and they caught the wind and broke

loose from the bridge. Everything started to shift on the sidewalk

towards Wacker Drive. The carpenters had to run out and bring

everything back and retie it. Then, we had a problem one year with

Onegin. The bottom of the tree was a hard piece, and the

rest of the tree flew [up into the space above the stage].

The top part would come in, and to make it look like one complete tree the

bottom part gave it a depth, and a little seat. I forget if it was

her or him who sat on it, but there were also all the flowers. Over

the course of the year, we had to make little flowers by hand and wire

them into the set. One day, during a kid’s show, that piece was sitting

out by the stage door, and after all the kids went by, there were no

more flowers on the tree! [Both laugh] They were all gone.

BD: They had become souvenirs of

their afternoon at the opera!

Gilbert: Yes.

BD: You also mentioned storing things in trucks?

Gilbert: After we had experienced

the stuff blowing away, we had the same problem again with the

huge set of Parsifal. It went up about twenty feet at the

back, and all those parallel pieces were big and unwieldy. So,

we rented trucks and brought them in. We took each section, which

was probably eight feet by eight feet by twenty feet high, and laid

them over and put them in the truck. We put two pieces in each

truck and sent it out, then brought another truck in, and keep going

like that to get rid of half the set that way. The rest of the

set we were able to store on the stage and live with it. That’s

the way the carpenters achieved those changeovers. That’s the advantage

of having a big storage space back there now, because what happens is

we still get jammed up a little bit. The big difference is that

now when we do an opera, even from opening night to closing night, the

backstage arrangement during the show is the same. No matter what

other show is taken in and put on, it looks pretty much the same if

we’ve got the room. If we have to put the entire hundred-and-some

chorus in one offstage spot to sing, there’s a spot to put them in,

and that spot stays there all the time. An offstage-band spot sometimes

gets pretty unwieldy and big, and that’s a problem getting in there.

In the old days, you could never count on it. We would do one

show, and the maestro would say, “This is a beautiful

nice spot here for the chorus, and a nice spot for the band, and everything

is great.” Three shows later, we bring

in another opera and set all the pieces up, and all of a sudden, he

walks in at 7:30 and looks around, and wonders, “What

happened to the room we had here? We can’t do this.”

I had to say, “Sorry, maestro, but we have to have

this set here, too.” That was a big problem.

That was the biggest thing we were relieved by having that

big garage area which builds into storage, so that on stage every night

is pretty consistent. It’s a big advantage.

BD: That’s what you really want,

then, is consistency from performance to performance?

Gilbert: Yes. I remember... especially

when there wasn’t enough room between the cyclorama and the scenery

offstage for the people to walk without brushing the cyclorama and making

the sky move. That made the lighting designer very unhappy because

everything is moving, with ripples in the sky, and clouds moving, and

the sun going away. There were some pretty horrendous times back then,

especially in the ’70s and ’80s

with things like that. It’s a lot easier, much better now.

BD: Thank you for

the conversation.

Gilbert: You’re welcome.

The theater at rest, with its traditional single light, awaiting

the activity of the following day . . . . .

The theater at rest, with its traditional single light, awaiting

the activity of the following day . . . . .

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on July 31, 1998.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that year, and again

in 1999. This transcription was

made in 2020, and posted on this website at

that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website,

click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie

was with WNIB,

Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975

until its final moment as a classical station in

February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared

in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he

now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected

transcripts of other interviews, plus a full

list of his guests. He would also like to call

your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

BD: What exactly is a prop man?

BD: What exactly is a prop man? BD: Do you ever have a caterer bring in real

food?

BD: Do you ever have a caterer bring in real

food? BD: Then you borrow it?

BD: Then you borrow it? Gilbert: It should be both, really.

The designers want everything usually to be perfect, but they are not

standing out in the front row looking at it. They come up on

stage, and stand there looking at things. I’ve had a designer tell

me that a piece of paper doesn’t feel right. [Laughs] I

told him that he wanted yellow paper, and that was yellow paper. Sometimes

it is a little bit aggravating because it’s over the top. It’s

more than it needs to be. Some singers insist on having the paper

with what they are singing written on the letter, or having what the

letter is supposed to say. They want it written on there.

That’s when someone has to go get it out of the book, and give it to me

so we can write it down.

Gilbert: It should be both, really.

The designers want everything usually to be perfect, but they are not

standing out in the front row looking at it. They come up on

stage, and stand there looking at things. I’ve had a designer tell

me that a piece of paper doesn’t feel right. [Laughs] I

told him that he wanted yellow paper, and that was yellow paper. Sometimes

it is a little bit aggravating because it’s over the top. It’s

more than it needs to be. Some singers insist on having the paper

with what they are singing written on the letter, or having what the

letter is supposed to say. They want it written on there.

That’s when someone has to go get it out of the book, and give it to me

so we can write it down.

BD: When you’re still down ten chandeliers,

can they go without ten chandeliers?

BD: When you’re still down ten chandeliers,

can they go without ten chandeliers? BD: Oh, it was a great scene.

BD: Oh, it was a great scene.

BD: Speaking of snow

— this time real snow — you

mentioned having to store sets outside of the building.

BD: Speaking of snow

— this time real snow — you

mentioned having to store sets outside of the building.