|

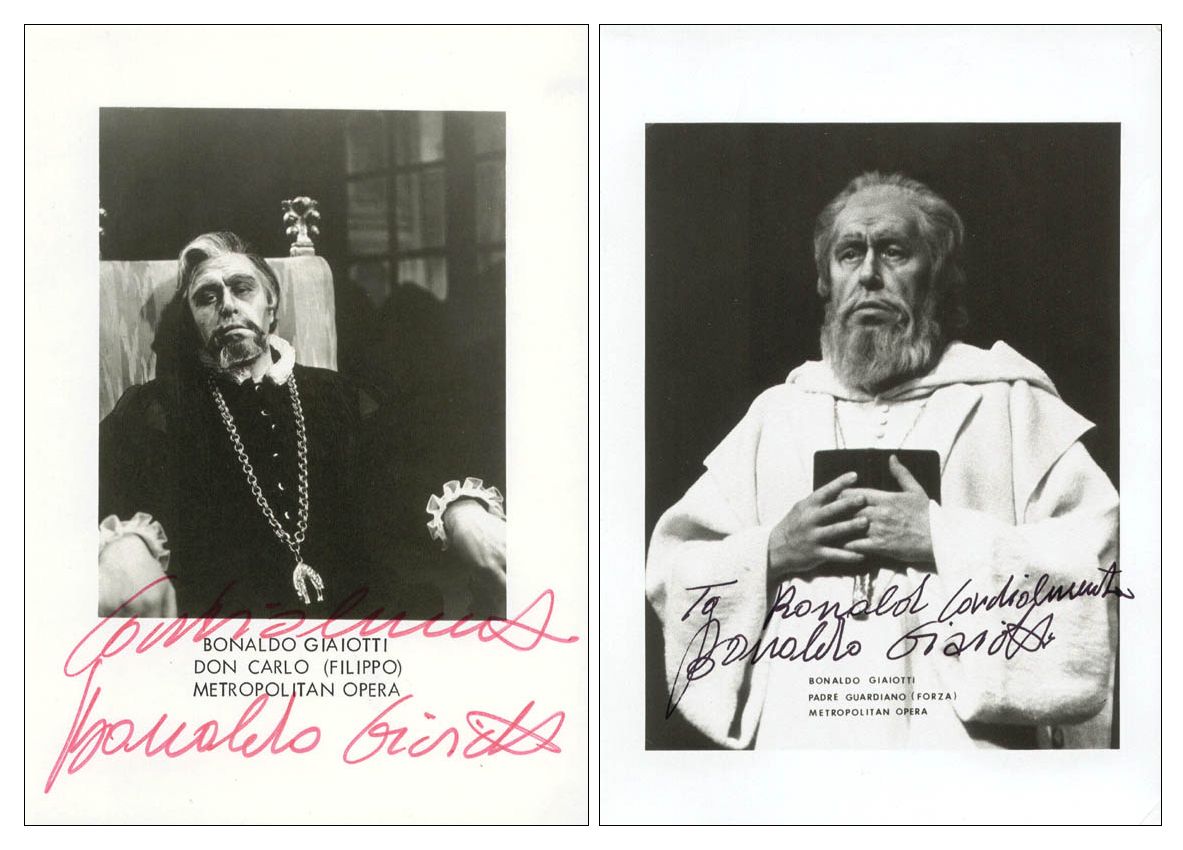

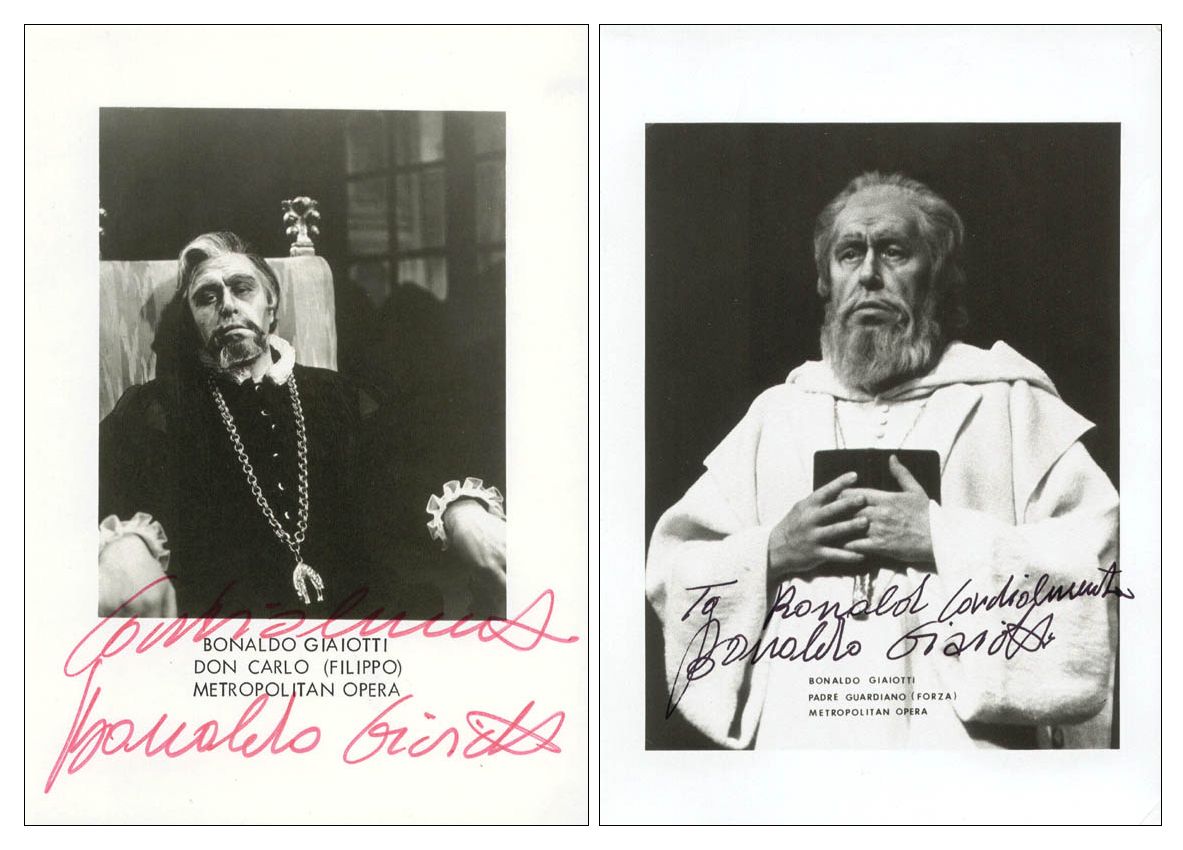

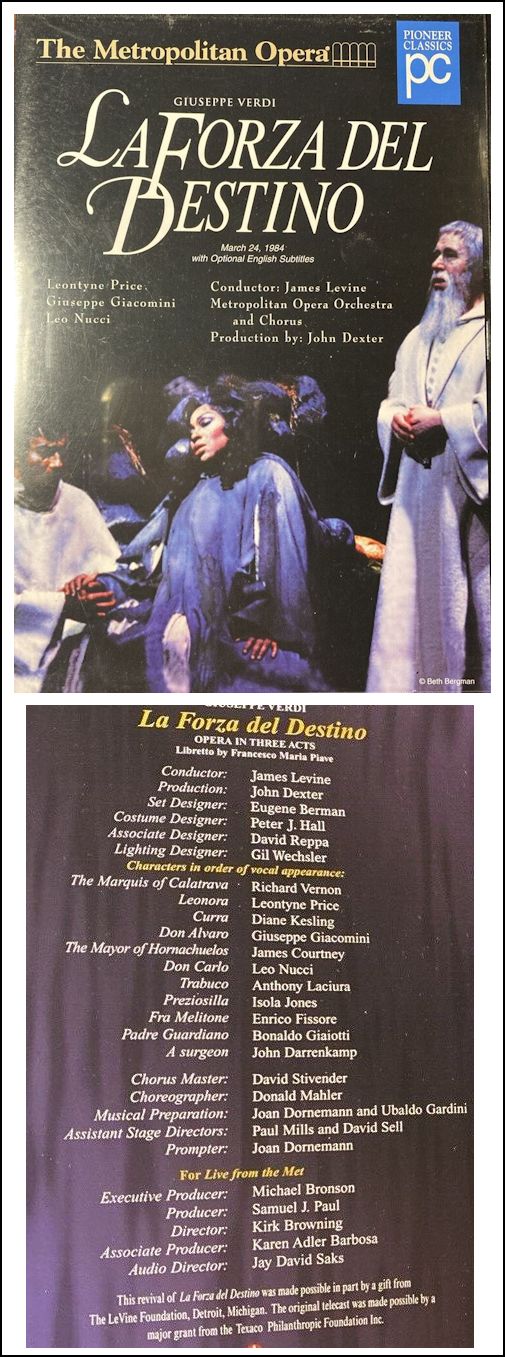

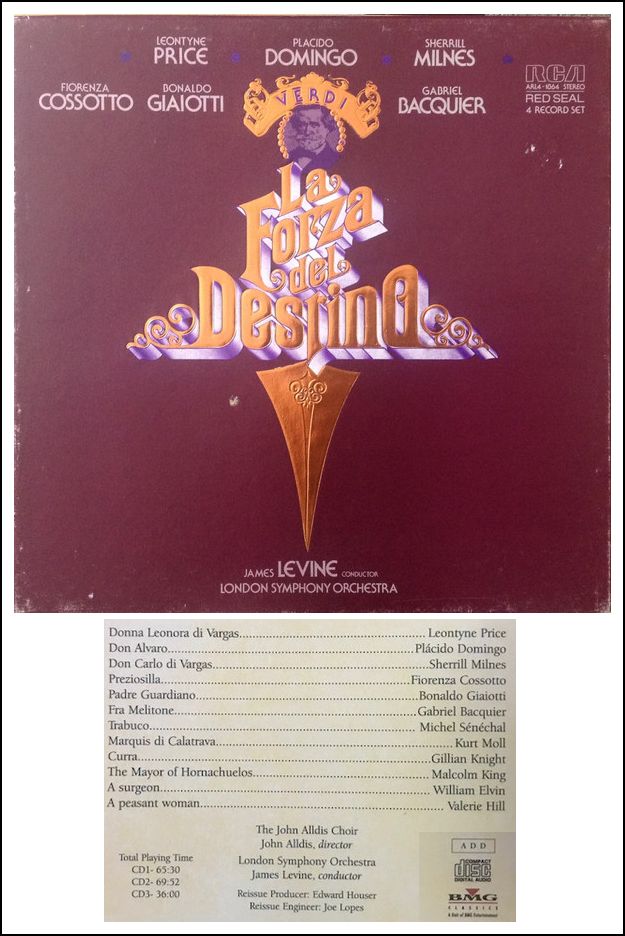

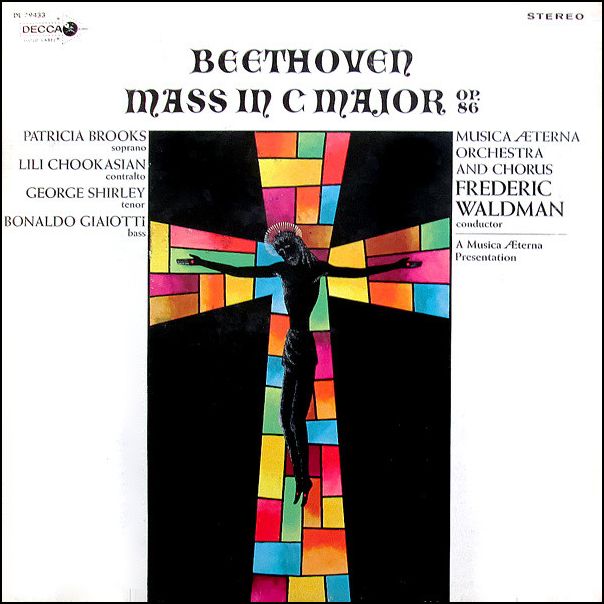

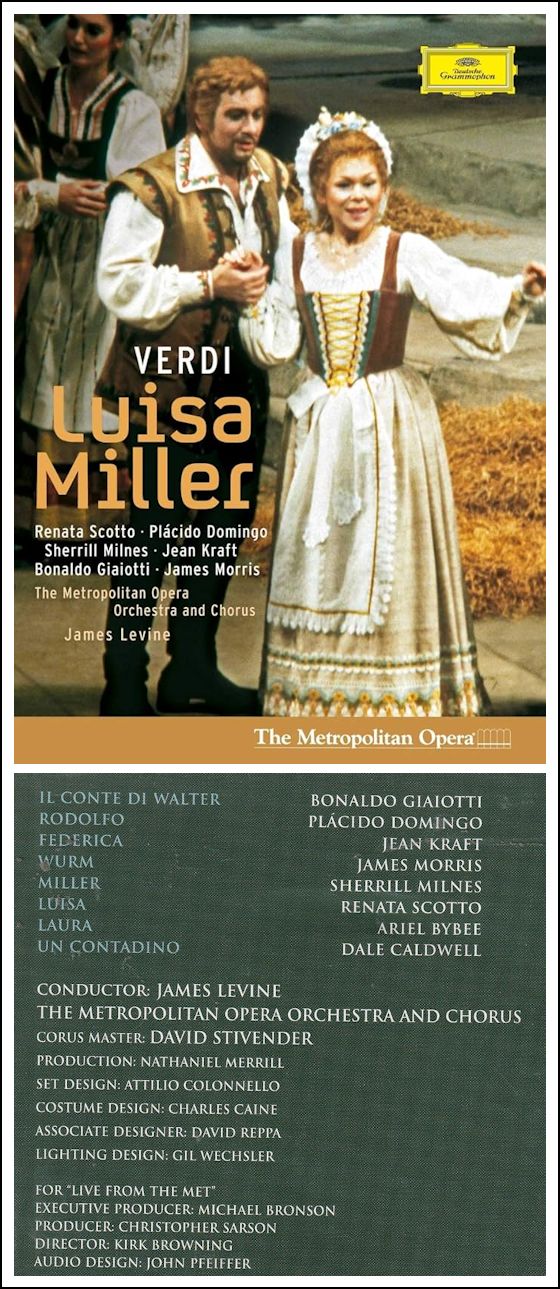

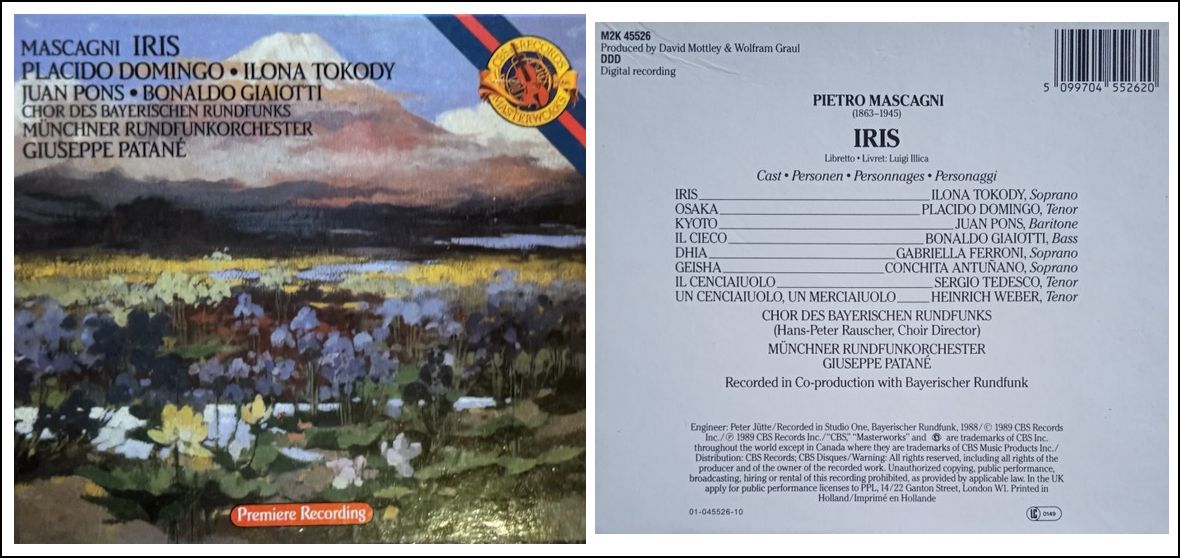

Bonaldo Giaiotti (25 December 1932 – 12 June 2018) was an Italian operatic bass, particularly associated with the Italian repertory. Born in Udine, he studied in his native city and later in Milan with Alfredo Starno, where he made his debut at the Teatro Nuovo in 1957. After singing with success in various opera houses in Italy, he made his American debut in Cincinnati, as Basilio in Il barbiere di Siviglia, in 1959. The following year he made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and remained with the company for 25 years, singing some 30 roles in over 300 performances, most often as Raimondo in Lucia di Lammermoor, Ramfis in Aida, and Timur in Turandot. Other roles included Padre Guardiano in La forza del destino, Phillip II in Don Carlo, Ferrando in Il trovatore, Count Walter in Luisa Miller, Zaccaria in Nabucco, Giorgio in I puritani, Commendatore in Don Giovanni, Alvise in La Gioconda, and King Heinrich in Lohengrin. He was heard in Donizetti's La Favorita at the Met in 2015 at the age of 81. Giaiotti also made several guest appearances in other major opera houses, including the Lyric Opera of Chicago, the Palais Garnier in Paris, the Vienna State Opera, the Teatro Real in Madrid, the Zurich Opera, the Royal Opera House in London, and the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires. From 1963 until 1995, he was a regular guest at the Arena di Verona Festival, notably as Verdi's Attila in 1985. His first appearance at La Scala was in 1986, as Count Rodolfo in La sonnambula. While best known for performing the Italian repertoire, Giaiotti did sing a number of non-Italian roles, notably the High Priest in Karl Goldmark's Die Königin von Saba (in 1991 at the Teatro Regio in Turin), Cléomer in Massenet's Esclarmonde (January 1993, at the Teatro Massimo), Cardinal Brogni in Halevy's La Juive, and the Anabaptist in Meyerbeer's Le Prophète, and, as noted above, King Heinrich in Wagner's Lohengrin (in 1976 and 1980, at the Metropolitan Opera). His evenly produced, beautiful and sonorous voice made him one of the leading bassi cantanti of his generation. |

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 13, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1991, 1993 and 1997. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.