|

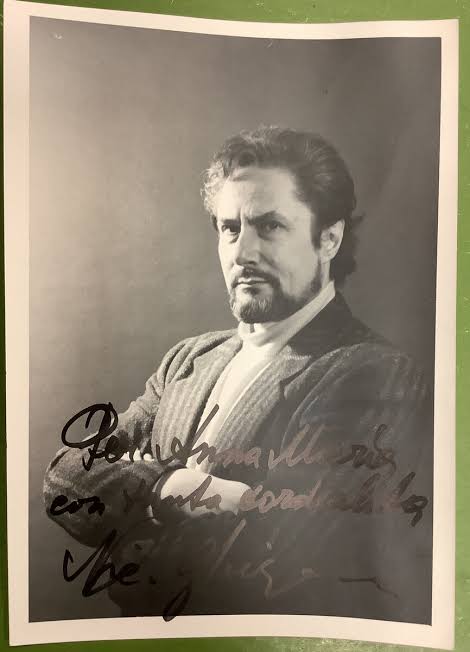

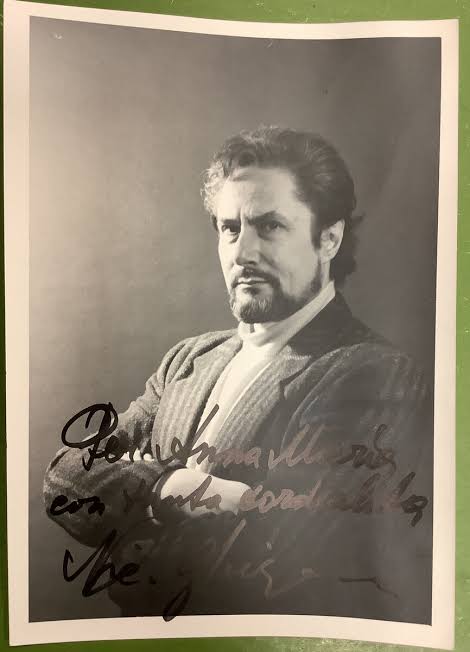

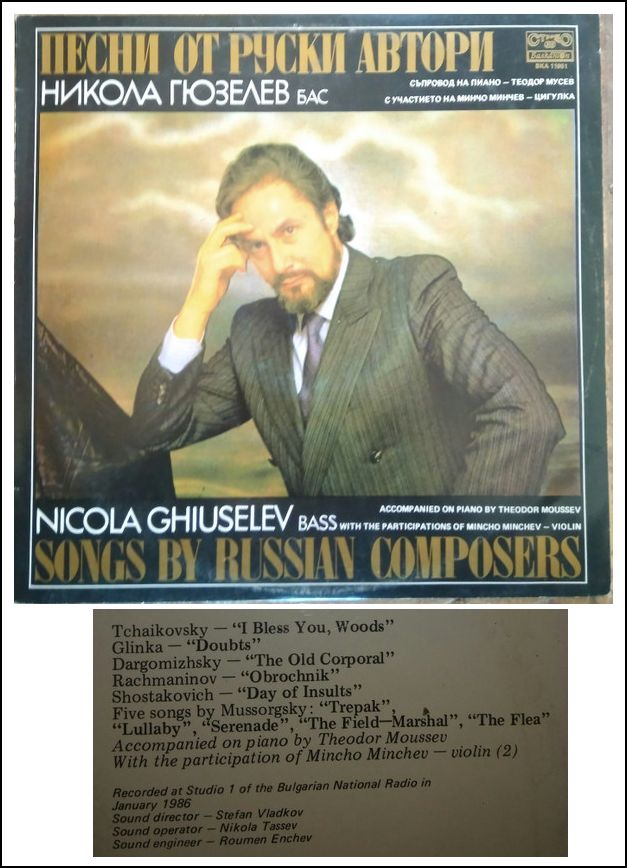

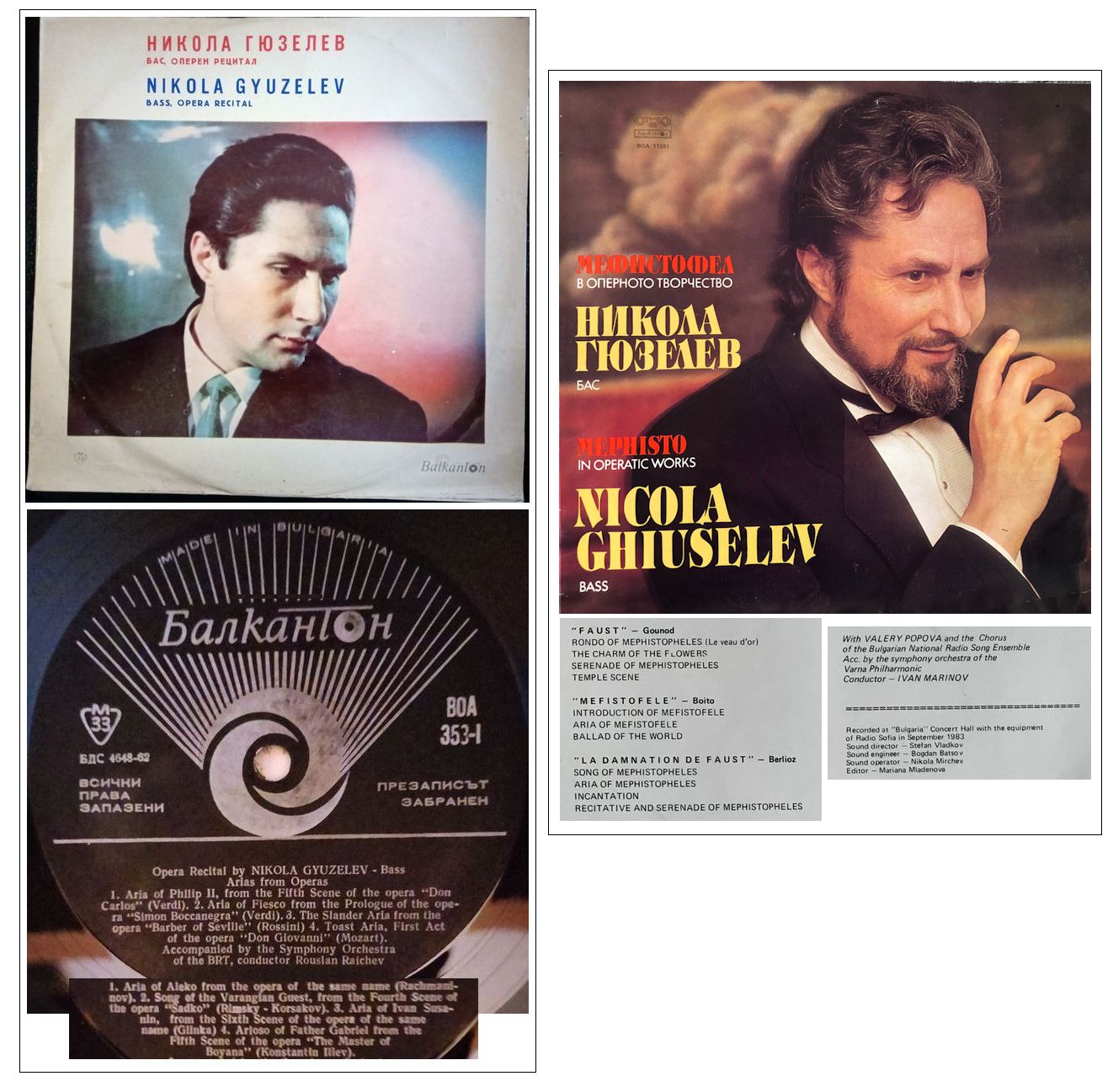

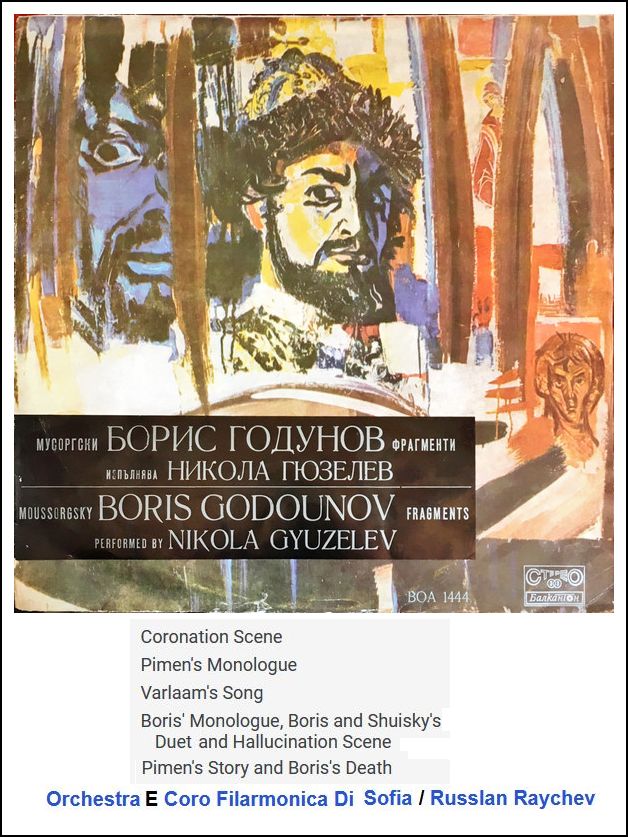

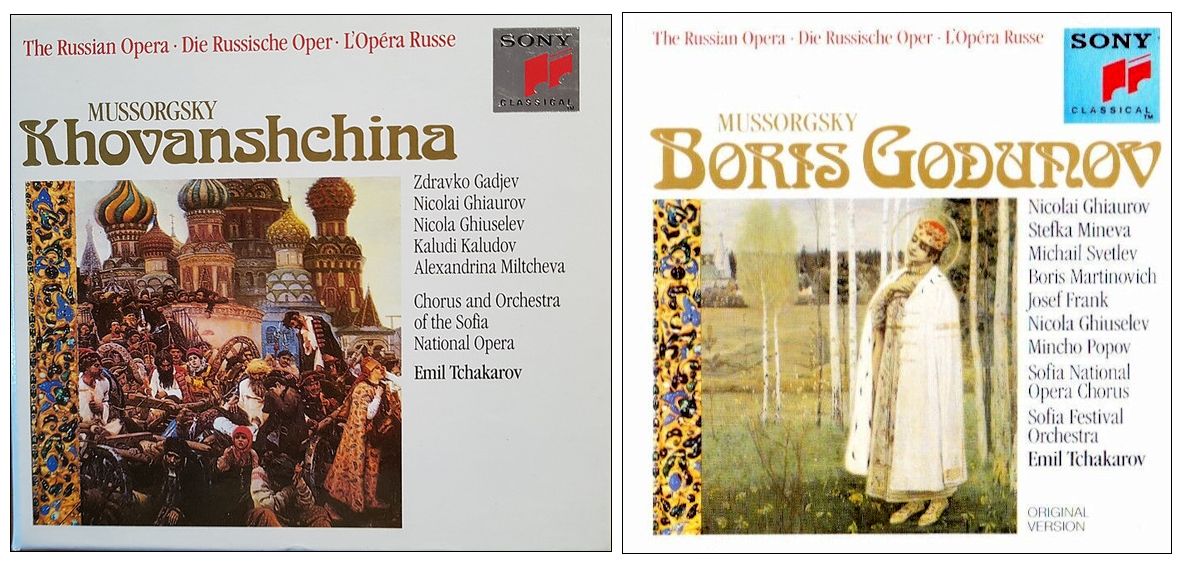

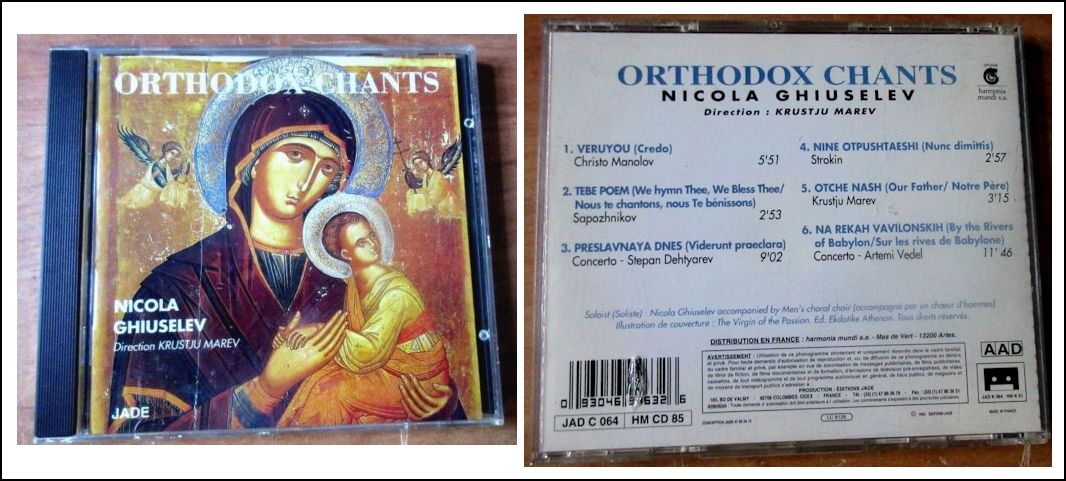

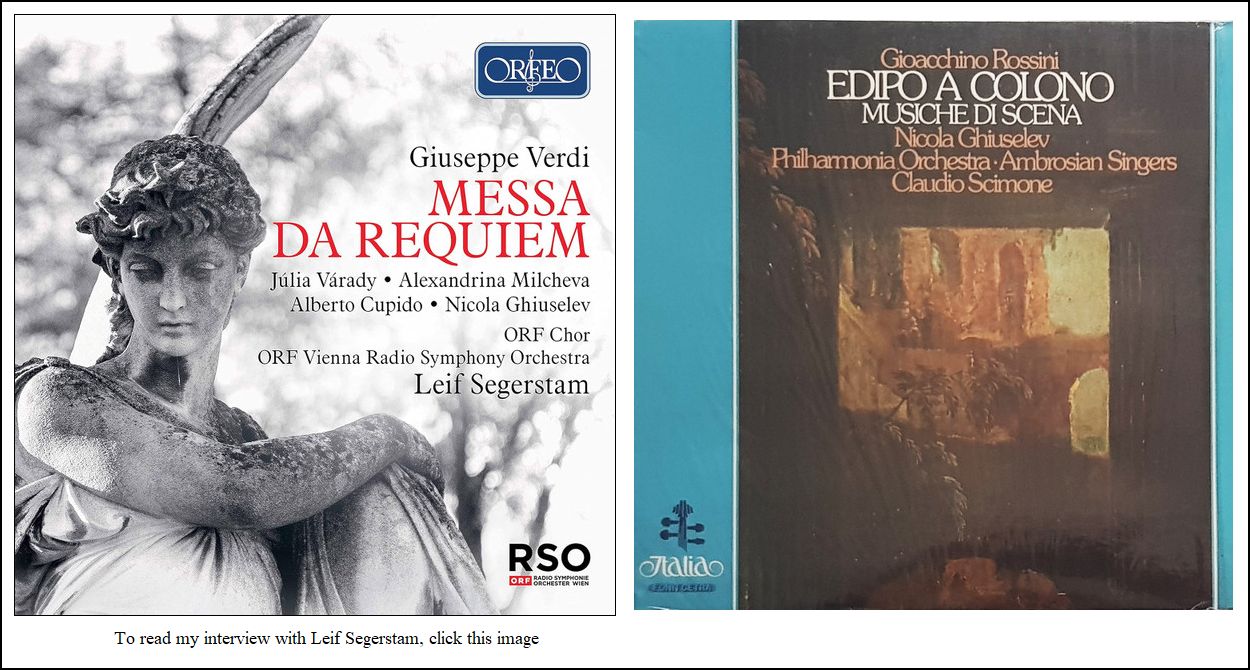

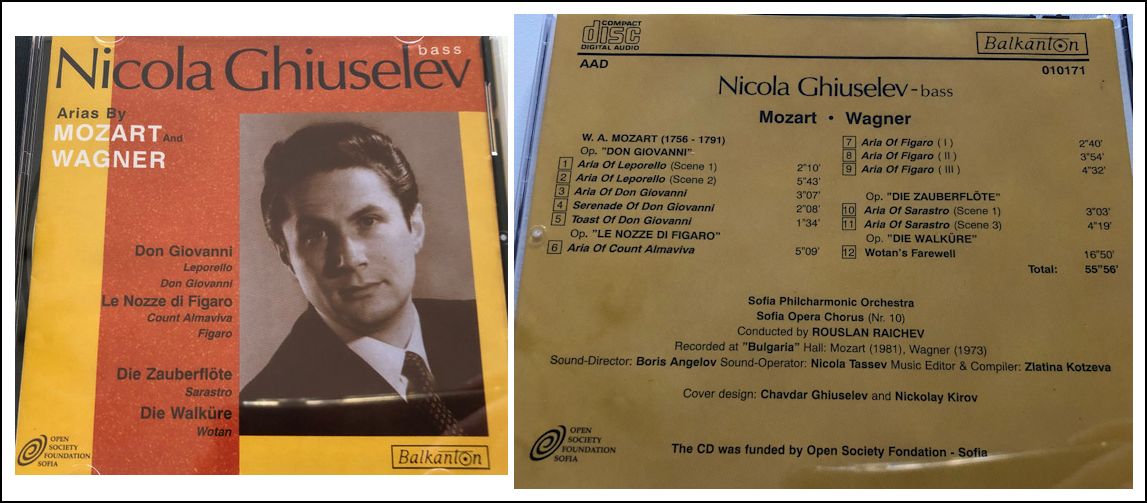

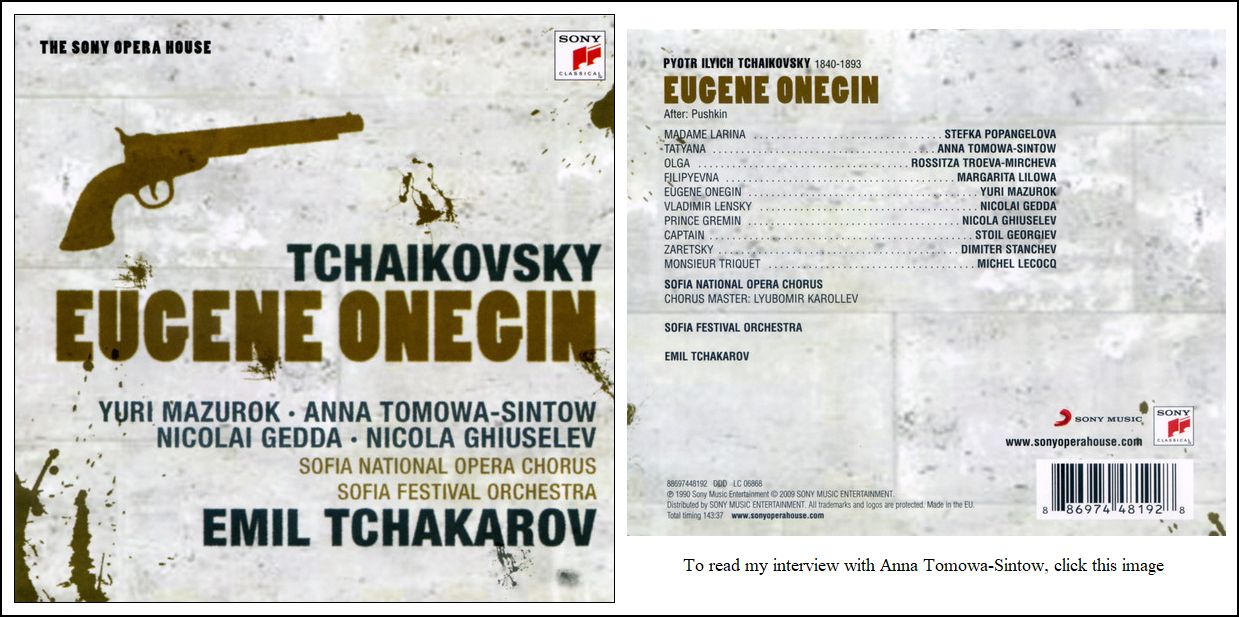

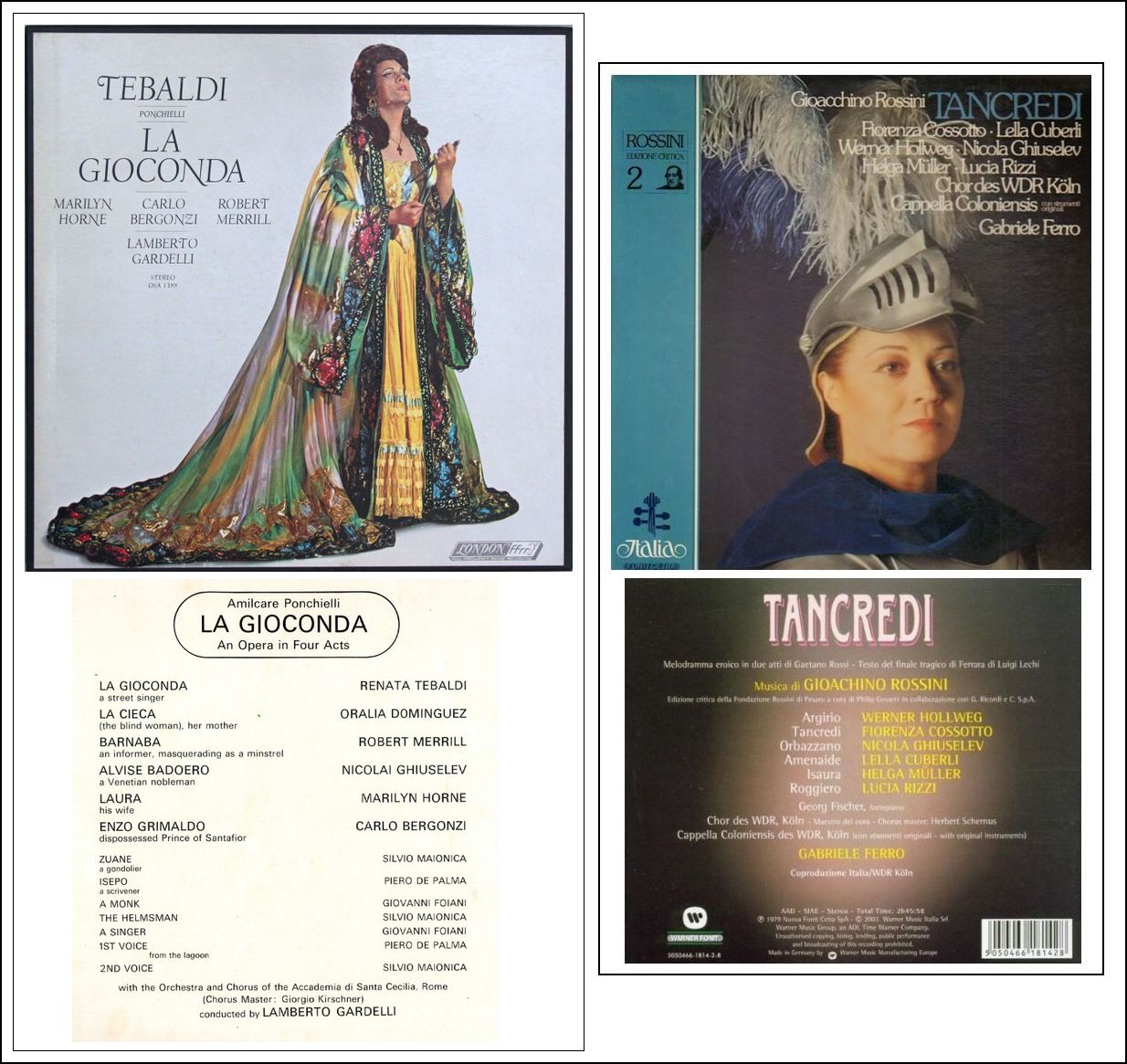

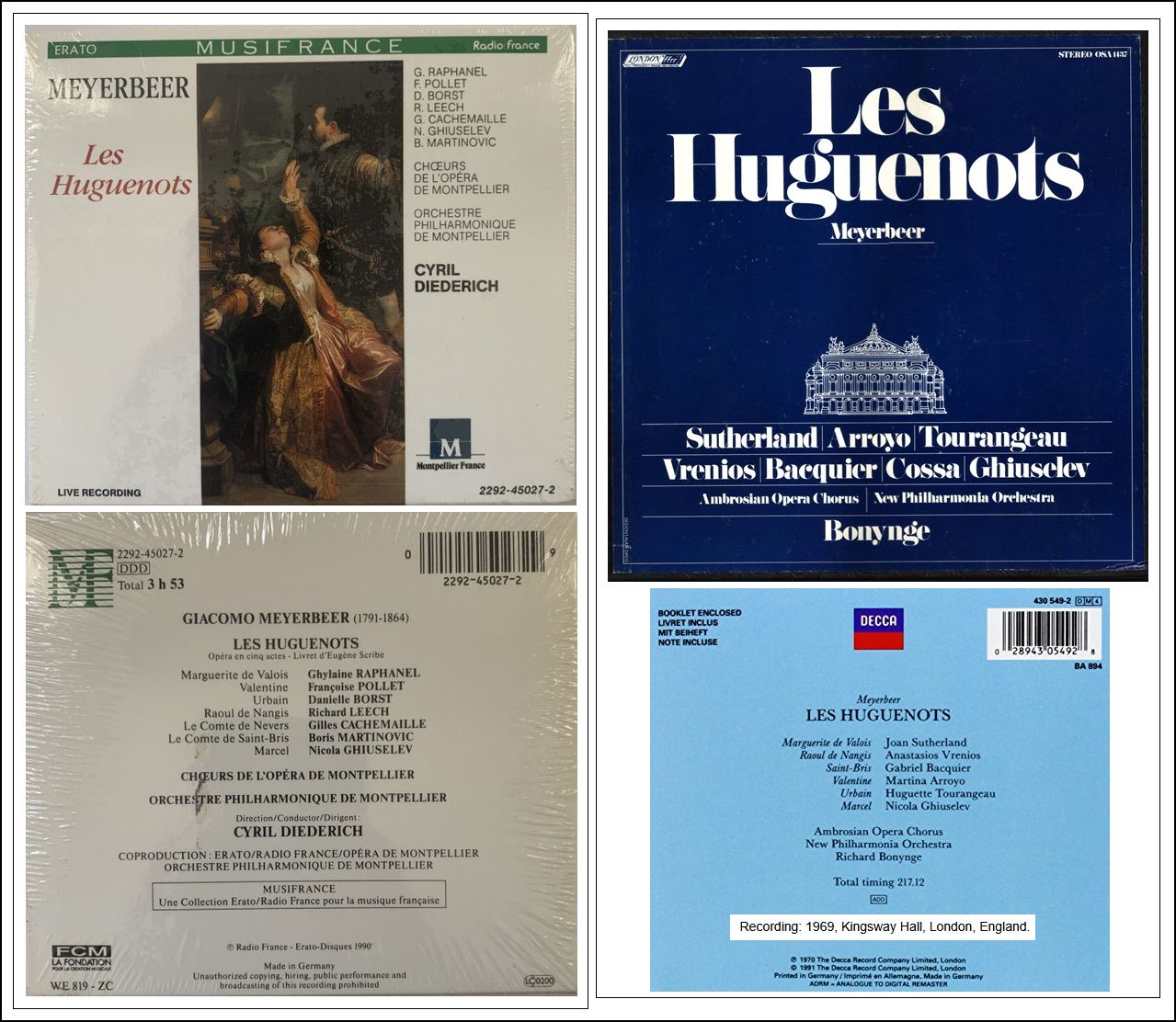

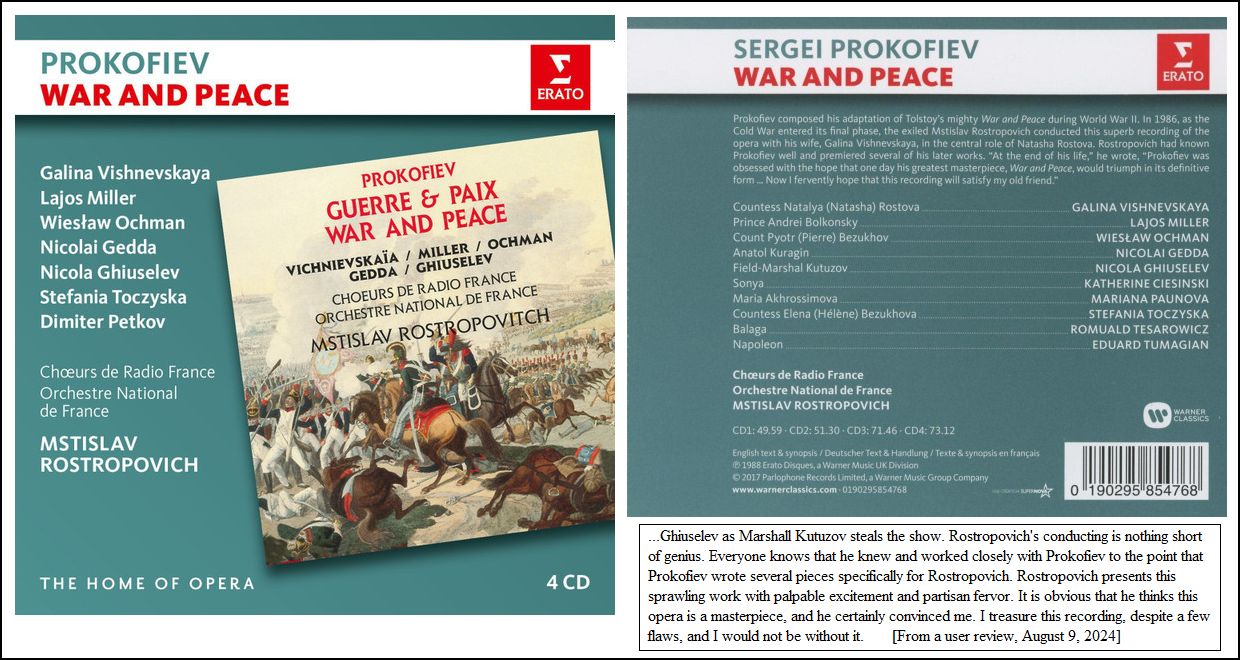

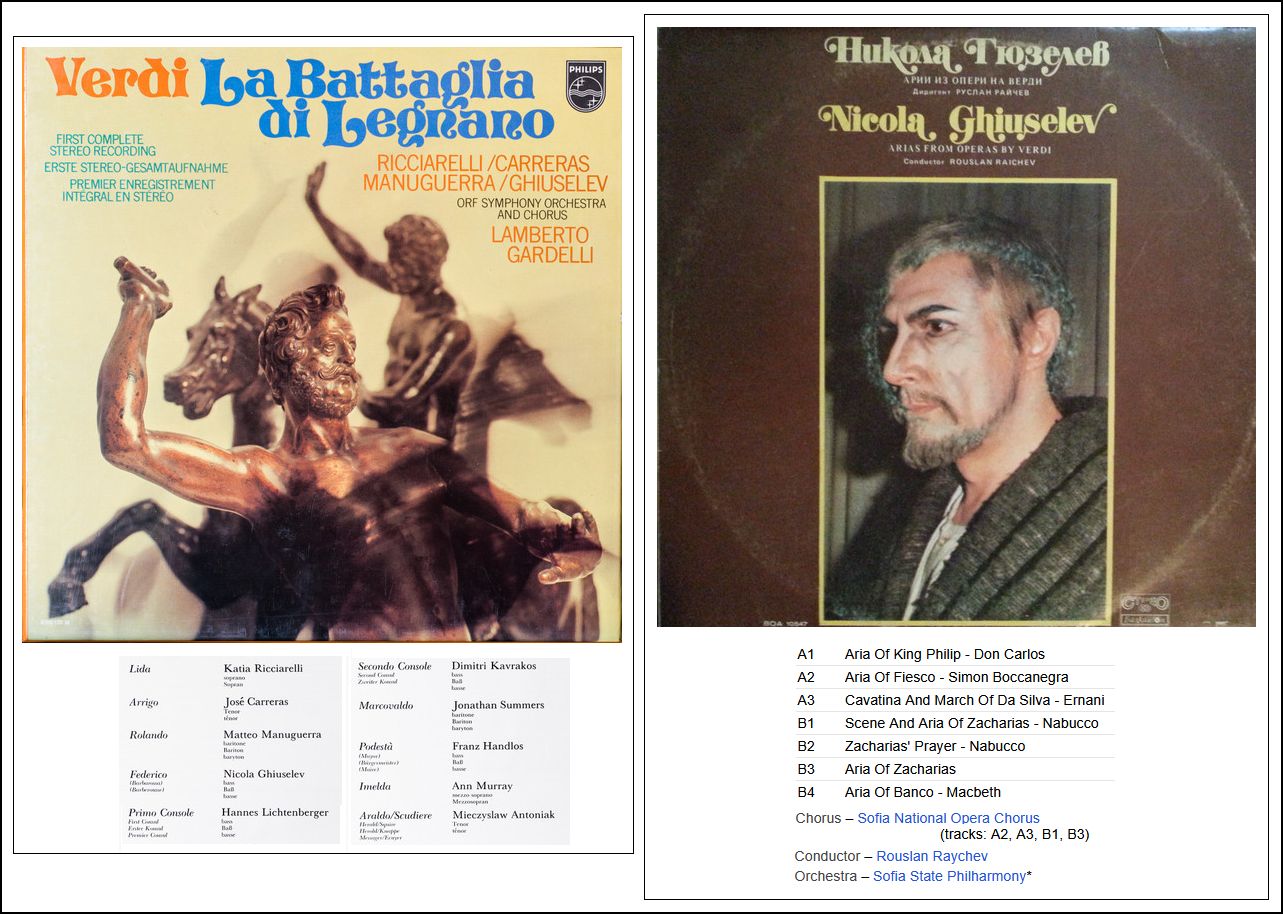

Nicola Ghiuselev (August 17 1936 in Pavlikeni, Bulgaria - May 16, 2014 in Sofia, Bulgaria). He studied painting at the Academy of Arts in Sofia, and later voice at the school of the National Opera of Sofia, with Christo Brambarov. He made his stage debut with that company, as Timur in Turandot, in 1960. In 1965, with the Sofia Opera, he toured Germany, the Netherlands and France, and made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera of New York, as Ramfis in Aïda, quickly followed by King Philip II in Don Carlo, and the title role in Boris Godunov. In two seasons with the Met, he also sang Raimondo in Lucia di Lammermoor, the Commendatore in Don Giovanni, and Colline in La bohème. Important debuts followed at the Berlin State Opera, La Scala in Milan, the Vienna State Opera, the Monte Carlo Opera, the Palais Garnier in Paris, the Liceo in Barcelona, the San Carlo in Naples, the Royal Opera House in London, the Verona Arena, the Salzburg Festival, and the Holland Festival. He also appeared in Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Prague, Budapest, Warsaw, Marseille, Toulouse, Chicago, and Houston, among others. Other notable roles include; Narbal in Les Troyens, Méphistophélès in Faust, Creonte in Medea, Padre Guardiano in La forza del destino, Banquo in Macbeth, Zaccaria in Nabucco, Silva in Ernani, Enrico in Anna Bolena, Galitzky in Prince Igor, the four villains in The Tales of Hoffmann, Mosè in Mosè in Egitto, Marcel in Les Huguenots, and Gremin in Eugene Onegin. |

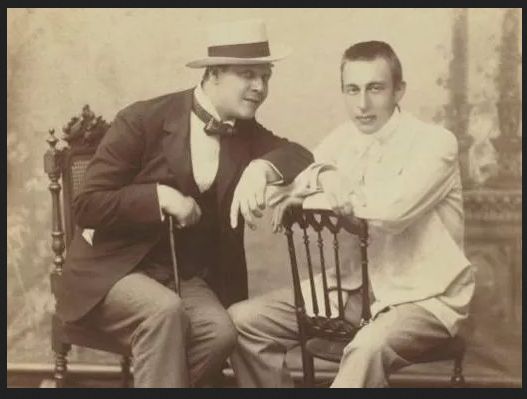

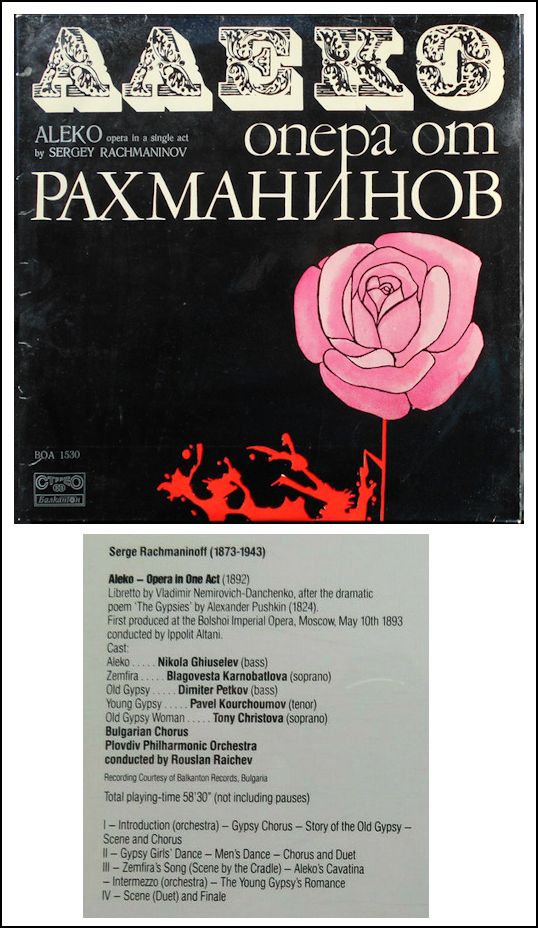

During his final year at the Conservatory, Rachmaninoff's request to take his final theory and composition exams a year early was granted, for which he wrote Aleko, a one-act opera based on the narrative poem The Gypsies by Alexander Pushkin, in seventeen days. It premiered in May 1892 at the Bolshoi Theatre. Tchaikovsky attended and praised Rachmaninoff for his work. Rachmaninoff believed it was "sure to fail", but the production was so successful the theater agreed to produce it starring singer Feodor Chaliapin, who would go on to become a lifelong friend. [Those two musicians are shown in the photo at left.] Aleko earned Rachmaninoff the highest mark at the Conservatory and a Great Gold Medal, a distinction only previously awarded to Taneyev and Arseny Koreshchenko. Zverev, a member of the exam committee, gave the composer his gold watch, thus ending years of estrangement. On May 29, 1892, at age nineteen, Rachmaninoff graduated from the Conservatory with highest honors in both composition and piano, and was issued a diploma which allowed him to officially style himself as a "Free Artist". Upon graduating, Rachmaninoff continued to compose and signed a 500-ruble publishing contract with Gutheil, under which Aleko, Two Pieces (Op. 2) and Six Songs (Op. 4) were among the first published. The composer had previously earned 15 rubles a month in giving piano lessons at a girls’ school... |

|

Marin Petrov Goleminov (Bulgarian: Марин Петров Големинов; 28 September 1908 – 19 February 2000) was a Bulgarian composer, violinist, conductor and pedagogue. Goleminov was born in Kyustendil, Bulgaria. The son of an attorney, he studied law before switching to music. He studied music at Sofia, Bulgaria, Paris, France, and Munich, Bavaria, Germany. Having returned to Bulgaria, he played the second violin in the famous Avramov Quartet (1935-38). He was one of the initiators of the foundation of the Chamber Orchestra of Radio Sofia and served as its conductor (1936-38). In 1943 he was appointed to the faculty of the Bulgarian State Academy of Music in Sofia to teach orchestration, conducting and composition. From 1954 to 1956 he served as Rector of the Sofia Opera, and as Director of the same organization from 1965 to 1967. In 1976 he was presented with the Gottfried von Herder Award of the Vienna University, and in 1989 was made an Academician of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. He died in Espinho, Portugal. Goleminov composed operas, such as Ivaylo, The Golden Bird, Zachariy the Zograph, Thracian Idols, the dance drama The Daughter of Kaloyan, four symphonies, eight string quartets, chamber music for various ensembles, etc. Goleminov was also a music publisher and author of theoretical works such as Problems of the Orchestration, Back to the Springs of Bulgarian Tonal Art, Behind the Scenes of the Creative Process. Goleminov's compositions draw heavily on the traditional rhythms

and melodic patterns of Bulgarian folk music, while also exploring more

modernist classical trends. His son Mihail was also a composer.

|

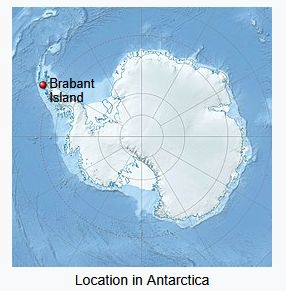

While some of my guests have local streets or monuments named for them, (and in the case of condutor Ferdinand Leitner, a bridge!), to the best of my knowledge, Nicola Ghiuselev is the only one to have a remote mountain given his name. Mount Ghiuselev (which is named after the Bulgarian opera singer) is the ice-covered mountain of elevation 1082 m in Avroleva Heights on Brabant Island (shown in map a right, and which is named for the Belgian province that is the locale of the opera Lohengrin) in the Palmer Archipelago, Antarctica. It has steep and partly ice-free north and northwest slopes, and surmounts Mitev Glacier to the northwest, Pampa Passage to the southeast and Svetovrachene Glacier to the southwest. Mount Ghiuselev is located at 64°13′17″S 62°07′25″W, which is 4.16 km south-southwest of Petroff Point, 3.8 km west-southwest of Mitchell Point, 3.1 km north by east of Einthoven Hill and 3.2 km east by south of Opizo Peak. |

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago, on December 11, 1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following day, and again in 1990, 1991, 1996 and 1997. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks go to Marina Vecci, Production Administrator of Lyric Opera, for providing the translation during our conversation. My thanks also to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.