|

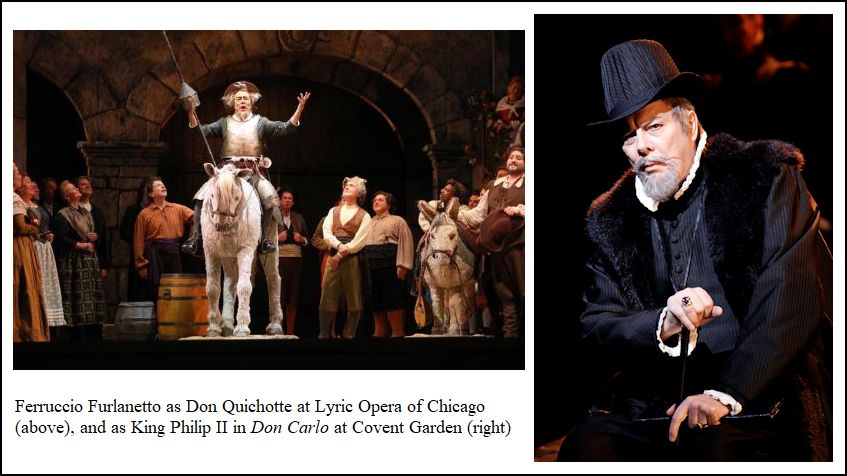

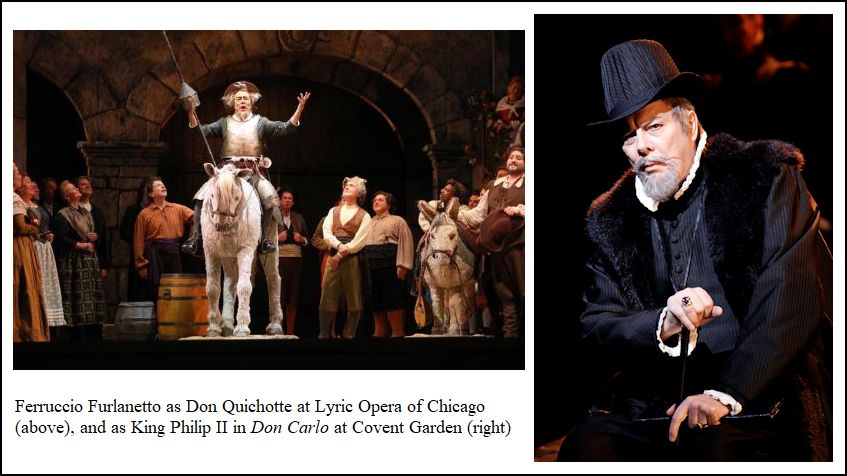

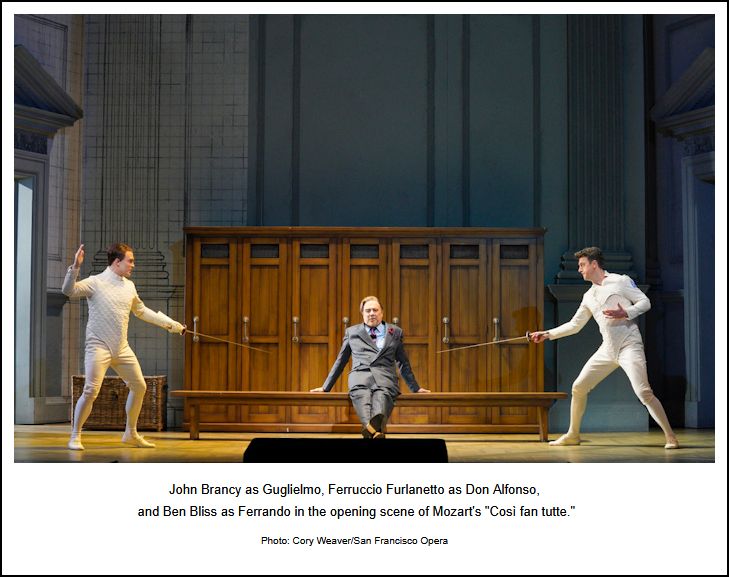

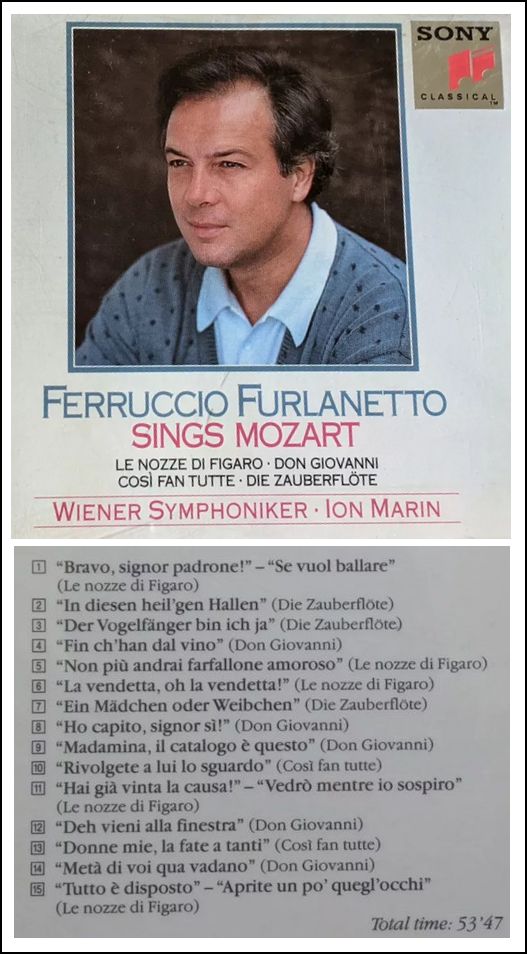

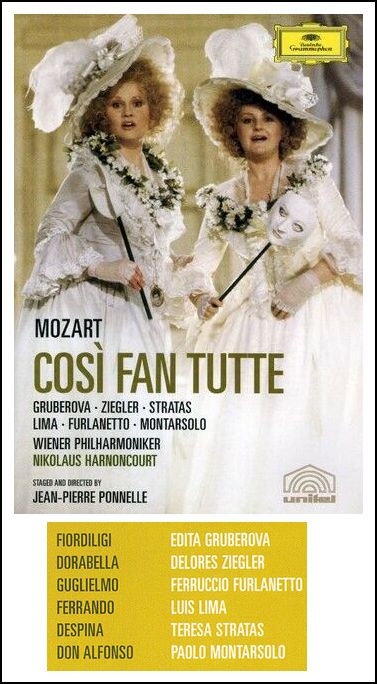

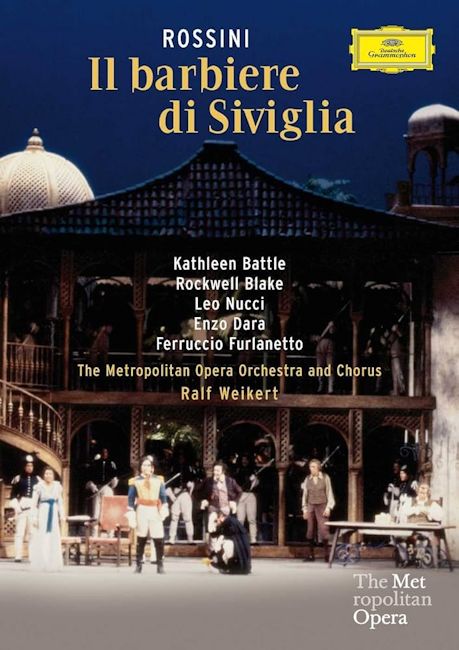

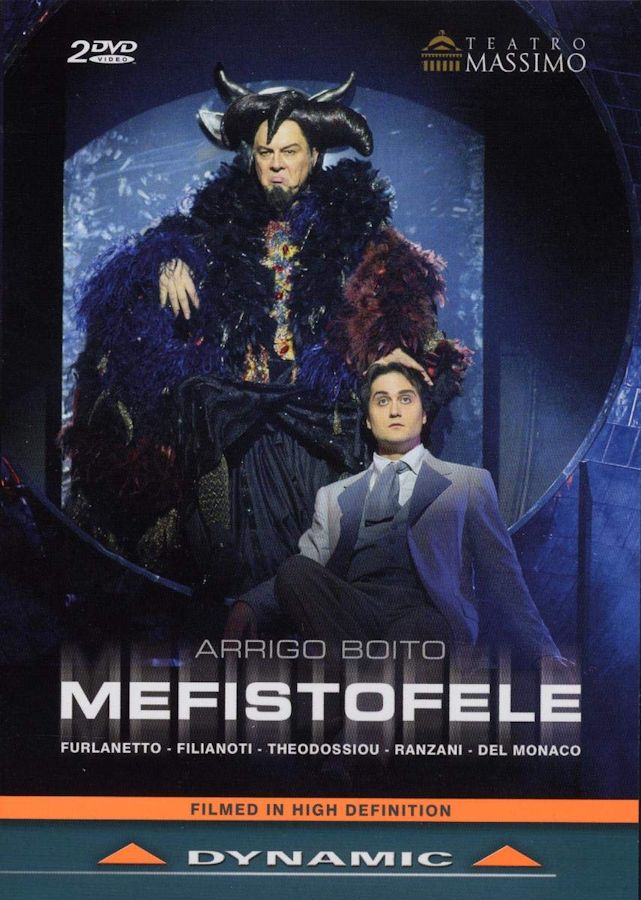

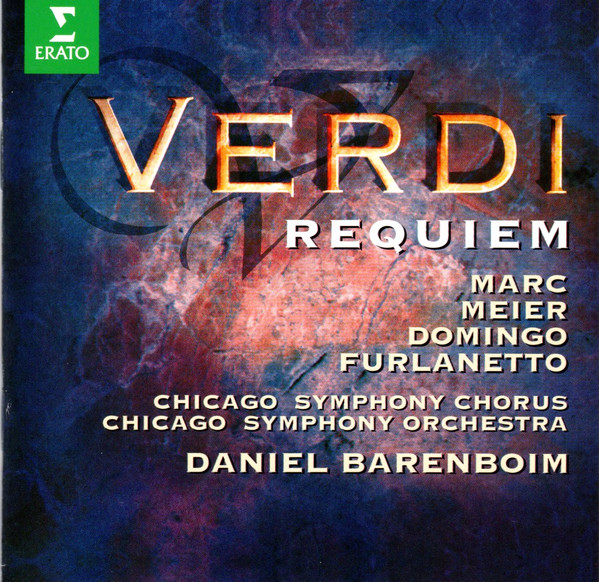

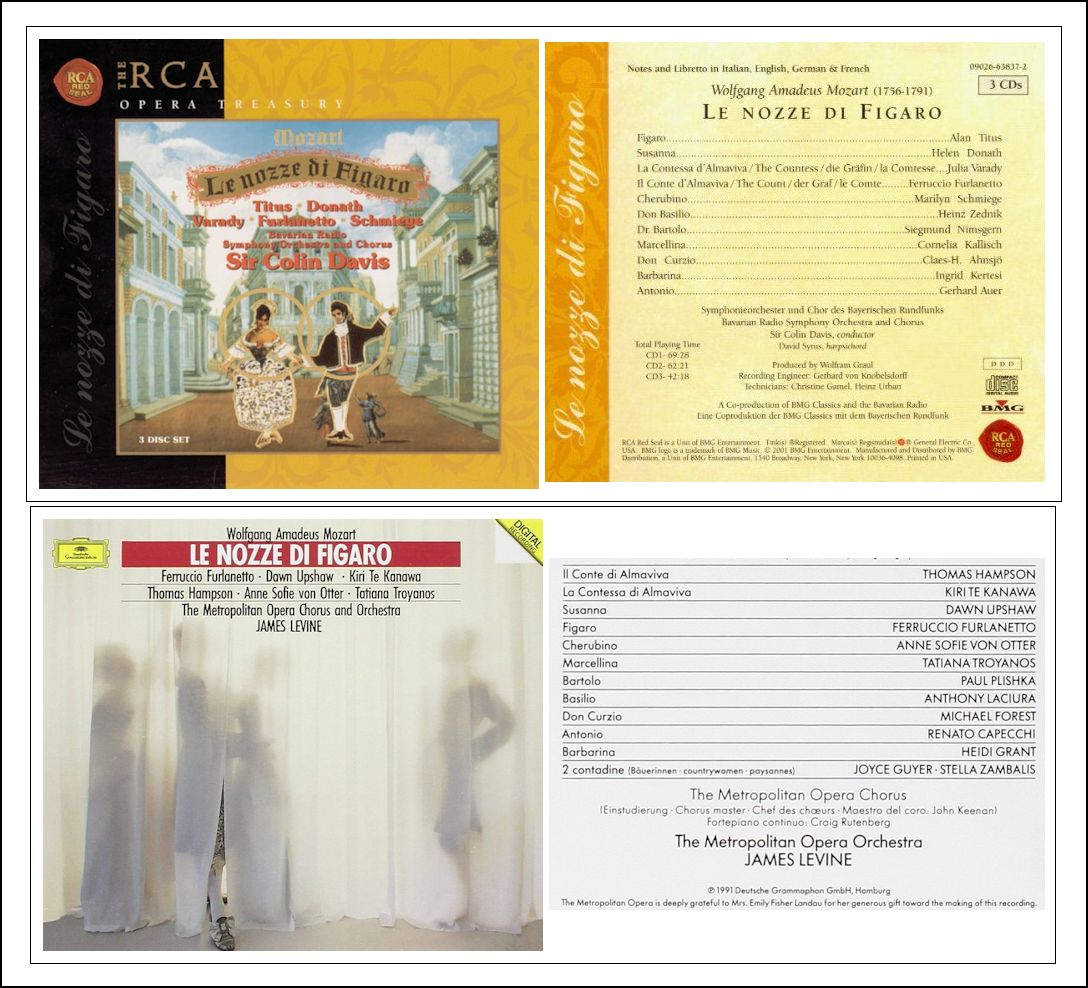

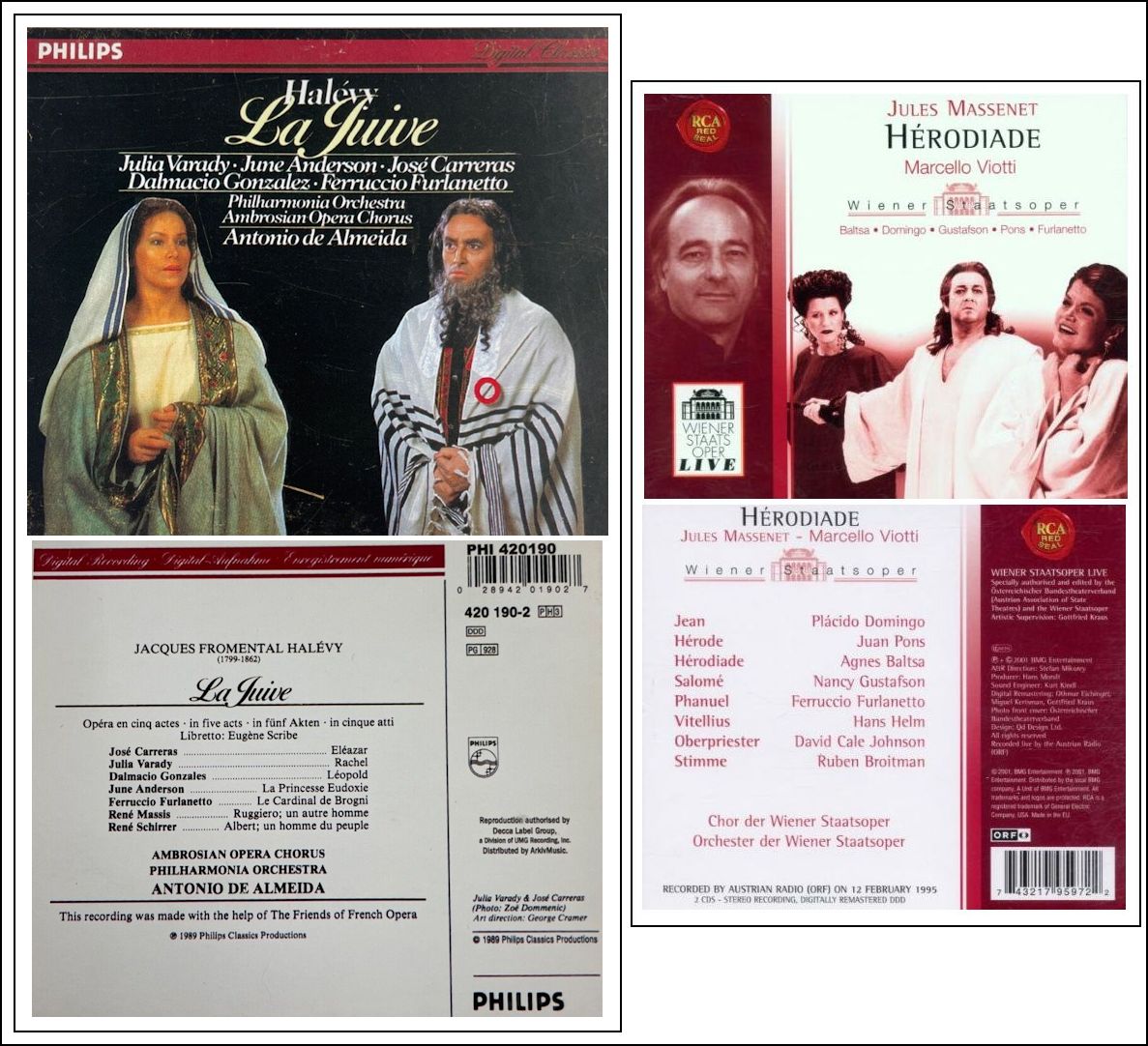

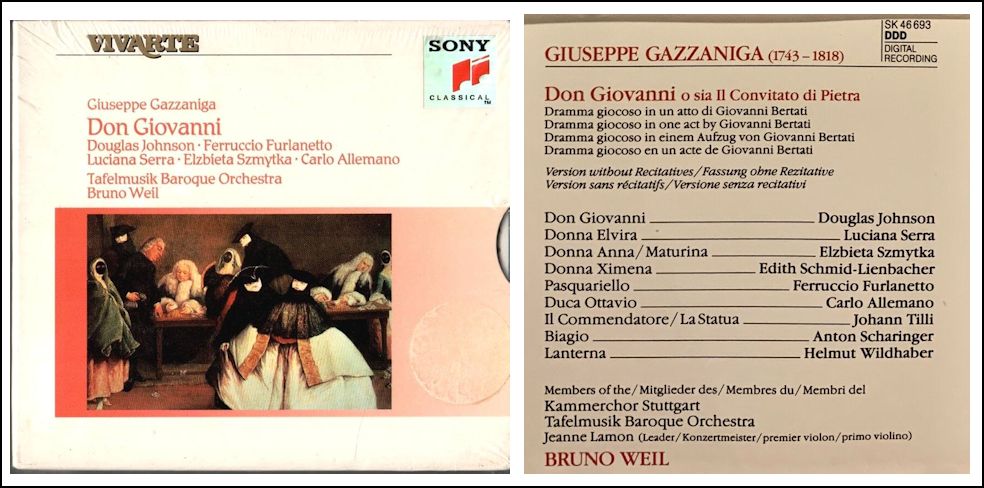

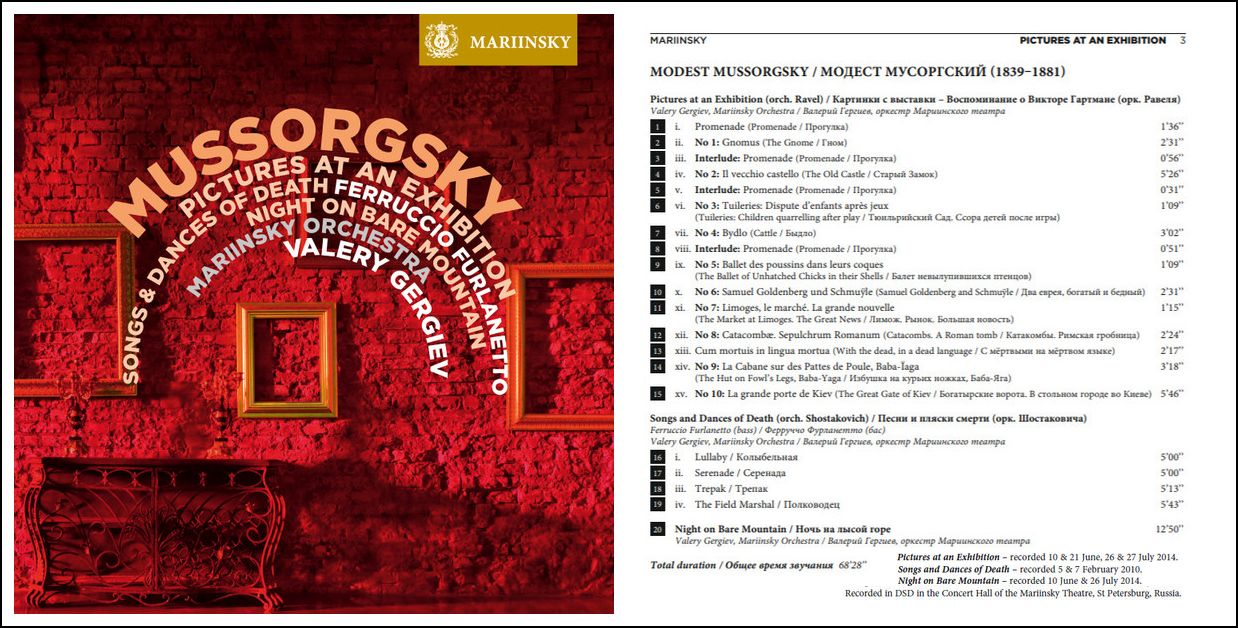

Ferruccio Furlanetto (born 16 May 1949 in Sacile, Italy) is an Italian bass. His professional debut was in 1974 in Lonigo. He debuted at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan in 1979, in a production of Verdi's Macbeth, conducted by Claudio Abbado. He has gone on to sing numerous roles, including both Don Giovanni and Leporello in Mozart's Don Giovanni, Philip II in Verdi's Don Carlos, Figaro in Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro, Gremin in Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin, Zaccaria in Verdi's Nabucco, Méphistophélès in Gounod's Faust, Orestes in Strauss' Elektra, Fiesco in Verdi's Simon Boccanegra, the title role of Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov, as well as many others. He debuted at the Metropolitan Opera in the 1980/81 season, and has performed at the Opéra de Paris (Bastille), the Salzburg Easter Festival and the regular Salzburg Festival, Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, the Vienna Staatsoper, the Tel Aviv Opera, and the Royal Opera House in London. His appearances in the United States have been primarily with the Metropolitan Opera and San Diego Opera. With the latter company he has sung the title role in Oberto (1985), Méphistophélès in Faust (1988 and 2001), the title role in Don Giovanni (1993 and 2000), King Philip in Don Carlo (2004), Basilio in Il barbiere di Siviglia (2006), and the title roles in Boris Godunov (2007) and Don Quichotte in 2009 and 2014. He reprised his performance in Don Quichotte in Palermo and in Mariinsky Theater (St.Petersburg) in 2010. In 2011 he sang the bass role in the Verdi Requiem, and his first US performance as Thomas Becket in Pizzetti's Assassinio nella cattedrale was in 2013. In 2021 he played Don Alfonso in the San Francisco Opera's production of Cosi fan tutte [shown below].

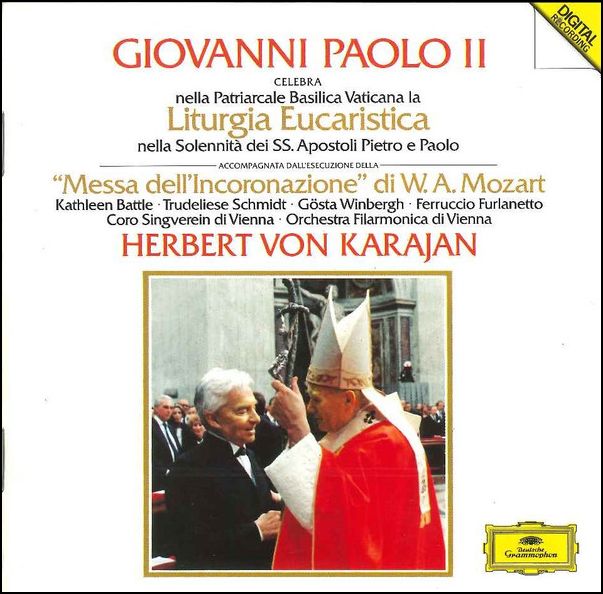

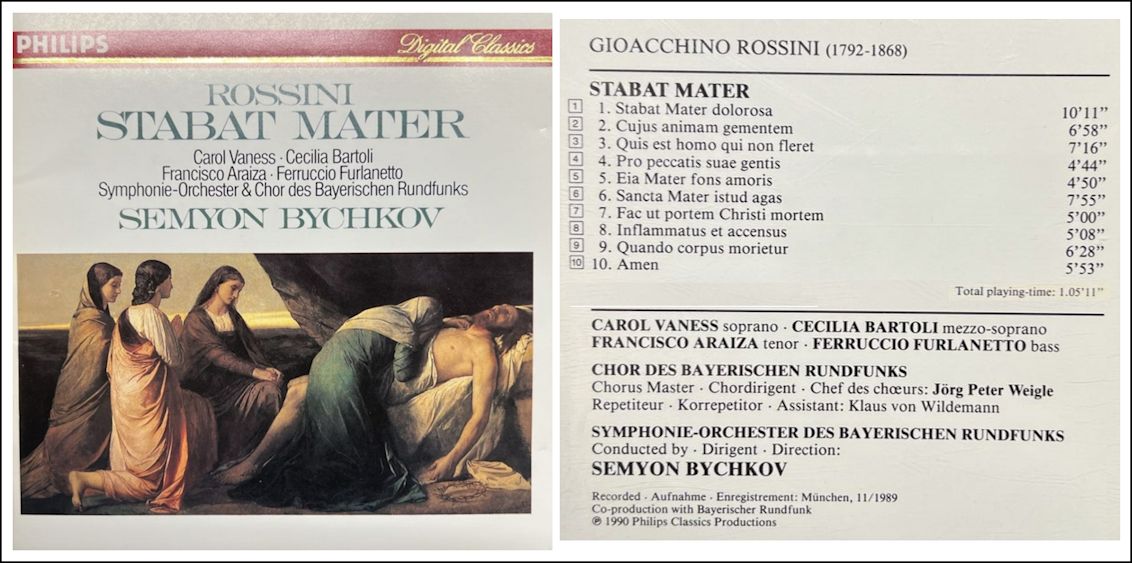

He is also widely in demand as a concert singer. He sang in Mozart's Coronation Mass under the baton of Herbert von Karajan, in an extraordinary performance at the Vatican in the presence of Pope John Paul II that was broadcast worldwide. He has appeared often in recital at La Scala, the Berlin Deutsche Oper, the Gran Teatro del Liceu of Barcelona, the Vienna Musikverein, the BBC Proms in the Royal Albert Hall, and many other venues. On DVD, Furlanetto can be seen as the Grand Inquisiteur in Verdi's

Don Carlos, in a production conducted by James Levine from the Met

in 1983. Also in the cast are Plácido Domingo, Mirella Freni, Grace Bumbry, Louis Quilico

and Nicolai Ghiaurov.

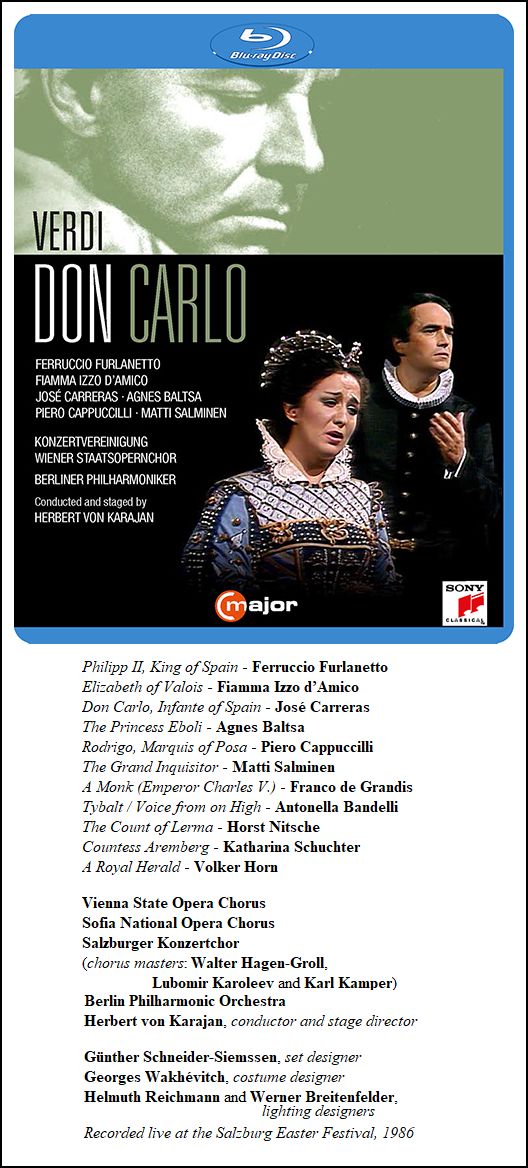

He can also be seen as King Philip II in the same work, under the

baton of Herbert von Karajan, with José Carreras, Fiamma Izzo

D'Amico, Agnes Baltsa, Piero Cappuccilli,

and Matti Salminen. Furlanetto is featured in a DVD of Mozart's Don

Giovanni, playing the part of Leporello, under the baton of Herbert

von Karajan conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in the 1987 Salzburg Festival.

Furthermore, Furlanetto plays the part of Sparafucile in Jean-Pierre

Ponnelle's 1982 production of Rigoletto with Ingvar Wixell,

Edita Gruberova, and Luciano Pavarotti, conducted by Riccardo Chailly.

He also appears in I Vespri Siciliani, a 1989 Scala production

conducted by Riccardo Muti. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

|

Kierkegaard's theological work focuses on Christian ethics, the institution of the Church, the differences between purely objective proofs of Christianity, the infinite qualitative distinction between man and God, and the individual's subjective relationship to the God-Man Jesus the Christ, which came through faith. Much of his work deals with Christian love. He was extremely critical of the doctrine and practice of Christianity as a state-controlled religion (Caesaropapism) like the Church of Denmark. His psychological work explored the emotions and feelings of individuals when faced with life choices. Unlike Jean-Paul Sartre and the atheistic existentialism paradigm, Kierkegaard focused on Christian existentialism. By the mid-20th century, his thought exerted a substantial influence on philosophy, theology, and Western culture in general. |

| La mère

coupable was the last play of Beaumarchais (January 24,

1732 - May 18, 1799), and it is rarely revived.

Like the earlier plays of the trilogy it has been turned into operatic

form, but has not entered the general opera repertoire.

The Count has been suspicious all these years that he is not the father of Léon, the Countess's son, and so he has been rapidly trying to spend his fortune to ensure the boy won't inherit any of it, even having gone so far as to renounce his title and move the family to Paris; but he has nevertheless held some doubts, and therefore has never officially disowned the boy or even brought up his suspicions to the Countess. Meanwhile, the Count has an illegitimate child of his own, a daughter named Florestine. Bégearss wants to marry her, and to ensure that she will be the Count's only heir, he begins to stir up trouble over the Countess's secret. Figaro and Suzanne, who are still married, must once again come to the rescue of the Count and Countess; and of their illegitimate children Léon and Florestine, who are secretly in love with each other. Figaro and Suzanne convince the Count and Countess that Bégearss is a bad man who is plotting against them. The disclosure of Bégearss's treachery brings the Count and Countess together. Almaviva, overwhelmed by relief at seeing Florestine saved from marrying Bégearss, is ready to forgo his fortune; Figaro, on the other hand, has no intention of letting the villain get away with the Count's money. The Countess adopts Florestine as her daughter and tells her not

to marry Bégearss; the Count adopts Léon as his son.

Bégearss returns from a notary, now in a strong legal position

over the Count's money. By complicated trickery led by Figaro, Bégearss

is finally outwitted and sent away empty-handed and furious. As it

is now established that Léon is the Countess's son but not

the Count's, and Florestine is the Count's daughter but not the Countess's,

there is demonstrably no kinship with a relative with a common ancestor,

and they are free to marry one another. As with the other Figaro plays, there are operatic versions, and as with the play itself, they are not nearly as well known as those made from the two earlier plays, and unlike the operas based on the earlier plays, adaptations of The Guilty Mother are rarely performed in the modern repertoire. The first proposal to turn The Guilty Mother into an opera was by André Grétry, but the project came to nothing. Darius Milhaud's La mère coupable (1966) was the first to be completed, and Inger Wikström made an adaptation called Den Brottsliga Modern (1990). In John Corigliano's The Ghosts of Versailles, there is a subplot in which the ghost of Beaumarchais, as an entertainment for the ghost of Marie Antoinette (with whom he is in love), conjures up a performance of the play as an opera: A Figaro for Antonia, claiming that by doing so he will change history and that Marie Antoinette will not be executed. In April 2010, the opera L'amour coupable by Thierry Pécou to a libretto by Eugène Green based on the Beaumarchais play, received its world premiere at L'Opéra de Rouen. Most recently, the play has been adapted by Icelandic singer, composer and librettist dr. Þórunn Guðmundsdóttir into the opera Hliðarspor, which is entirely in Icelandic. The title is a double entendre for stepping to the side and having an extramarital affair. All three operas were staged, the earlier two pieces in new Icelandic translations, in succession in December 2024 - March 2025 with numerous singers taking part in more than one of them.

|

See my interviews with June Anderson, and Nancy Gustafson

See my interviews with Carol Vaness, Francisco Araiza, and

Semyon Bychkov

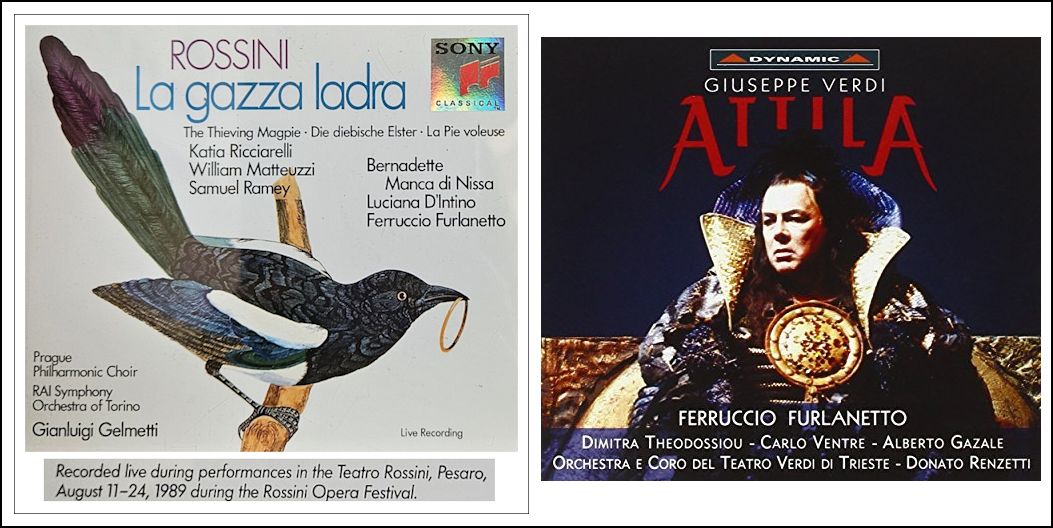

See my interviews with Bernadette Manca di Nissa,

and Donato Renzetti

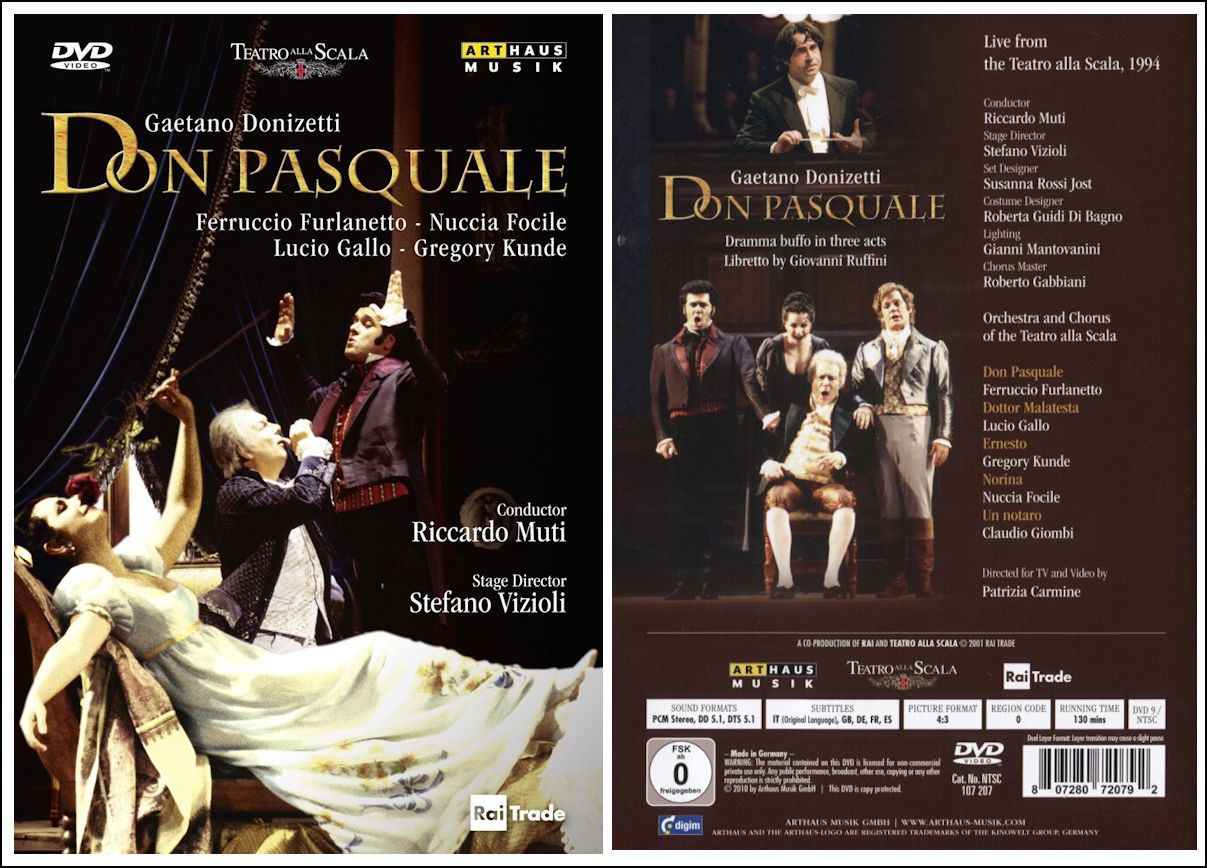

See my interview with Gregory Kunde

© 1992 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 3, 1992. Portions were broadcast on WNIB three months later, and again in 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.