Jerry Fuller

Performer and Scholar of the

Double Bass and Violone

A conversation with Bruce Duffie

Jerry Fuller began studying the double bass at age 16 and was invited to

join the Lyric Opera of Chicago orchestra three years later. Within two years

he was promoted to first desk of the double bass section in addition to performing

with the Santa Fe Opera. Mr Fuller has also served as solo double bass of

The Musikkollegium Winterthur Switzerland. While in Europe, Mr. Fuller became

interested in historically-informed performance practice and has achieved

international recognition for his work with period instruments. A Chicago

Artists Abroad grant recipient, Mr.Fuller’s performances in London, Rome,

Geneva and Edinburgh have been broadcast worldwide. In addition, Mr. Fuller

has performed at the Ravinia and the Aspen Music Festivals and both the Boston

and Berkeley Early Music Festivals.

Jerry Fuller began studying the double bass at age 16 and was invited to

join the Lyric Opera of Chicago orchestra three years later. Within two years

he was promoted to first desk of the double bass section in addition to performing

with the Santa Fe Opera. Mr Fuller has also served as solo double bass of

The Musikkollegium Winterthur Switzerland. While in Europe, Mr. Fuller became

interested in historically-informed performance practice and has achieved

international recognition for his work with period instruments. A Chicago

Artists Abroad grant recipient, Mr.Fuller’s performances in London, Rome,

Geneva and Edinburgh have been broadcast worldwide. In addition, Mr. Fuller

has performed at the Ravinia and the Aspen Music Festivals and both the Boston

and Berkeley Early Music Festivals.

His recordings on the Musical Arts Society, Cedille and Centaur labels have

been hailed by both critics and colleagues. Mr. Fuller also writes on period

instruments and performance practice for The Strad, Double Bassist, and Bass World magazines, serves on the editorial

board of the Online Journal of Bass Research

and is webmaster for the Double Bass and

Violone Internet Archive.

Mr. Fuller served as an officer of the Board of Directors of the International

Society of Bassists 1990-1996 and has appeared as a guest artist with the

American Bach Soloists of San Francisco, the Handel and Haydn Society of

Boston and the Newberry Consort of Chicago.

He is principal double bassist of the Haymarket Opera, Callipygian Players

and The Bach Institute at Valparaiso University. In addition he is Director

of both ArsAntiguaPresents.com and the Midwest Young Artists Early Music

Program for which he was awarded the Early Music America Outreach Award for

Excellence in Early Music Education.

Jerry also has received a Special Recognition Award for Historically Informed

Performance from the International Society of Bassists. This award is given

once every two years to a bassist who has demonstrated and achieved the highest

level of excellence in historically informed performance.

-- From the Ars Antigua Website.

Ars Antigua is an affiliate of Early Music America and member of Early Music

Chicago.

|

In the name of full disclosure, I am happy

to report that Jerry Fuller is a long-standing friend of mine... and it was

not until I just typed that sentence that I realized the phrase ‘long-standing’

also applies to his position with his chosen instruments! Indeed, we

talk about that later in the interview.

In the name of full disclosure, I am happy

to report that Jerry Fuller is a long-standing friend of mine... and it was

not until I just typed that sentence that I realized the phrase ‘long-standing’

also applies to his position with his chosen instruments! Indeed, we

talk about that later in the interview.

We have stayed in touch over the years, and have many friends in common.

We also have a mutual interest in Northwestern University, and while I was

teaching there (2002-11), I asked Jerry to come and do an instrumental demonstration

for my Music 101 class. He

brought another friend with him, the gambist Phillip W. Serna, as well as

a third instrument, as can be seen in the photo of all of us at right.

[Serna also appears in the final photo at the bottom of this webpage.]

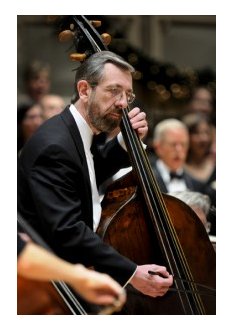

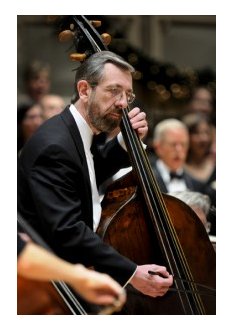

No stranger, himself, to teaching, the next photo below shows Fuller giving

a demonstration and workshop for the Midwest Young Artists in Lake Forest,

IL, in 2006. The other photos on this page show Fuller in performances

at various venues with Ars Antiqua, the Baroque Band, and the Callipygian

Players.

In the spring of 1997, I wanted to present a special program featuring his

recordings and comments on WNIB, Classical 97, where I was announcer/producer

from 1975-2001. He liked the idea, so we got together at his home that

June for this conversation.

I began with what seemed to be an obvious question . . . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Why

the double bass?

Jerry Fuller: I

remember when I was sixteen years old, going to a concert in my little hometown

in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, where the Milwaukee Symphony was playing a concert

at Wayland Academy. My parents saw them there regularly. My father

had played the violin in his youth, though I had never witnessed either of

them performing on a musical instrument. I was intrigued, and still

remember the concert very well. The big work was Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony. It was totally

random, but for some reason I was placed in front of the double bass section,

and as I observed all of this, the bass clearly seemed to be having the best

time of any group in the orchestra. And the sound was just phenomenal

to my ears! At intermission I went up and talked to Roger Ruggeri,

the principal bass then and who is still principal bass there. He is

a very fine player.

BD: You had not

played violin or trumpet before this?

JF: No, no.

A little bit of piano, but really nothing. It was like a thunder bolt

that struck me, so I asked him at intermission, “I’d love to take lessons

on the double bass. Who could I do this with? He said, “In this

little town I’m not sure what you’re going to do.” But in Madison,

Wisconsin, there was a very fine teacher, Vera Olson, and he suggested that

I contact her. So I did that and then I made the trip to Madison, which

was a bus ride away, every Saturday, and started taking lessons.

BD: Being sixteen,

though, you were tall enough so you could handle the instrument?

JF: Exactly, right.

The world has evolved and progressed, in one sense, in the intervening time.

It was typical back in the late 1960s and early 1970s that one would wait

until they were in high school, or large enough to get their hands around

this instrument. Now there are programs all around the world for young

students, seven, eight, nine years old, to play on half-size and smaller

double basses. There are makers out there today that are making those

instruments, and there are wonderfully dedicated teachers that are teaching

very young students, and getting them started much earlier on the bass.

BD: Is it better

to start on the double bass, or to start on the violin and transfer to the

double bass? Or maybe start on the cello and transfer to the double

bass?

JF: I’m biased.

I think going right to the double bass is a wonderful thing to do, especially

with the instruments that are available now and the fine teachers that are

available now. Go right to the instrument and learn that literature

and the techniques and the unique sounds, and everything that’s special about

the double bass right from the beginning.

BD: Does it still

surprise people that it can be a solo instrument?

JF: Yes, but less

so. It’s interesting. The year I started, Gary Karr put out his very

first recording, a wonderful recording, but prior to that there were maybe

one or two recordings available that featured the double bass at all.

I remember after my second or third lesson in Madison, going into the local

record store and finding a recording by Georg Hörtnagel, from Germany,

doing Dittersdorf’s Concerto and

Sinfonia Concertante with viola.

That was all there was! It was a marvelous sound, a marvelous recording,

and then the famous Gary Karr recording came out, which everybody knows.

Now there are pages and pages and pages of CDs and recordings in the catalogue,

so that has contributed enormously to the visibility of the double bass,

and to people’s awareness.

BD: [With a gentle

nudge] I hardly think the double bass is something that can be invisible.

[Both laugh]

JF: That’s true.

BD: Are there times

when you wish you’d taken up the piccolo?

JF: Only on long

plane rides. I’ll never forget... I was traveling to Rome with William Ferris, the Chicago

composer who had written a marvelous piece for tenor, harp, and double bass,

which we were going to perform at the Vatican. [This, along with

another Ferris piece, were recorded, and the CD is shown near the bottom-right

on this webpage. The tenor soloist is John Vorrasi.] I

got on the plane with the double bass, and sat it in the seat next to me.

BD: Did you have

to buy a ticket for it?

JF: Oh absolutely!

There was an older Italian lady who did not speak English at all, but certainly

got her point across about what she thought of having a double bass sitting

next to her. [Both laugh again]

BD: Not very happy,

was she?

JF: No. It

can be a little bit tense times, but there are benefits. You always

get an extra meal on the flight...

* *

* * *

BD: You not only

play the standard double bass, but you also play a baroque instrument of

that size?

JF: Yes.

As the years went along, I’ve acquired an interest in musical genealogy,

if you will. One of the ancestors, or the ancestor, to the double bass

is an instrument called the violone. It’s a fascinating world to me,

and the terminology is a little bit complex, in the sense that this one term

‘violone’ really refers to at

least three slightly different instruments. The earliest known reference

to the violone was in the mid-1500s, the mid-16th century, and in fact I

have a reproduction of an instrument that’s now in the Nuremberg museum.

It’s a contrabbasso violone in the sixteen foot register, the same register

as a double bass, but it is a six-stringed fretted instrument that’s tuned

an octave below the viola da gamba, the bass viola da gamba. So it’s

a D to D tuning. That instrument was widely used in that era between

1550 and, say, 1700. By 1680 it was starting to fall out of use.

BD: Are the strings

tuned in fourths like in the double bass?

JF: Fourths and

thirds like a viola da gamba, which is interesting. If you look at

the modern orchestra today, the violin family is violin, viola, cello, and

their ancestors were always of the violin family. There’s this myth

that circulates every now and then that their ancestors were really the gambas,

but they’re really a separate family. The gamba family is a separate

family, but the modern double bass grew out of the gamba family, whereas

the modern other stringed instruments really grew out of the violin family,

and evolved from there. [For a further discussion of the gamba,

see my interview with gambist Mary Springfels.]

BD: When you’re

playing the double bass, though, you have the strings tuned in fourths?

JF: In fourths.

BD: And it has

no frets?

JF: That’s correct.

BD: So it’s a completely

different fingering of the left hand?

JF: Yes, they are

different tunings. The D-tuned violone contrabbasso is a different

tuning, and it’s a wonderful tuning for low consort music of the German and

Italian repertoire.

BD: So you have

to go back and forth between those two, the old and the new?

JF: Yes, yes, yes.

BD: Does that make

you schizophrenic at all?

JF: [Laughs]

Well... there’s some question whether I was that way before these two instruments

or not... but it takes a little bit of you getting used to. The more

one does it, the more facile one comes to do this. But there is a little

bit of that. So that’s one member of the violone family. There’s

another instrument that was in use at the time that’s also known as the violone,

and it’s a G violone. It’s a violone da gamba and it’s tuned a fourth

lower than the bass viola da gamba.

BD:

Is it written at pitch or is it a transposing instrument?

BD:

Is it written at pitch or is it a transposing instrument?

JF: It’s written

at pitch. It’s not a transposing instrument, as the double bass is,

one octave down, and as is the violone contrabbasso is, one octave down as

well. When you read it on a G violone, it is at pitch. So the

top four strings are tuned G, D, A, F or E, depending on which source you

look at, but very similar to a double bass, only an octave higher.

Then there are two more strings, a C and a G, so it starts getting you into

that sixteen foot register as well. This is a marvelous chamber music

instrument, and was most widely used before the steel strings or the wound

string for the cello, which were invented around 1680. This violone

da gamba was really used as the main bass or continuo instrument prior to

that time. Then there’s more. In terms of violone in the late

1700s and early 1800s, there’s something called the Viennese violone, which

was a five stringed instrument. From top to bottom it would go A, F-sharp,

D, A, F-natural, in the sixteen foot register. In this very short period

in terms of history, only twenty-five years or so, a huge golden age of solo

repertoire for the Viennese violone grew up with those people. In fact,

Mozart wrote a concert aria Per Questa

Bella Mano for baritone and violone.

BD: Where does

Dragonetti fit into all of this?

JF: He was slightly

later, and he was playing on an instrument that was tuned one of two ways

— the way a modern double bass is, G to A, or he was known, at

times, to perform on a three stringed instrument, G, D, G. So you can

see the history of this instrument is one of great creativity and experimentation.

BD: Has it settled

down now to where there is a standard double bass?

JF: Relatively,

compared to the terms we’ve been talking in, yes. It tends to be a

four stringed instrument, G, D, A, E from top to bottom, and tuned in fourths.

However, compared to the violin, it’s interesting. When you talk to

orchestral musicians about auditions, if they hear a violinist play and then

they hear a bass audition, they are always amazed at the different approaches,

styles, ways of tuning, that the double basses still have relative to a violin.

If someone’s playing a Tchaikovsky violin concerto, it’s a big deal whether

they move over one string or not. It’s a very standardized repertoire

pedagogically, and in the approach to the instrument. This certainly

is not true today for the double bass. I just returned from a trip

to Paris, where I was just amazed. We heard a marvelous performance

of Carmen at the Opera Bastille,

and the bass section played exactly alike. Their instruments were all

of similar shape and similar make. They all played with a French bow

and they all had a similar sound. When you come to a symphony orchestra

or opera orchestra here in the United States, one person’s playing a German

bow, another’s using a French bow, and their basses are of all different

sizes. Some have five strings on them. Most have four with low

C extensions, and they all studied with different people and they have very

different influences.

BD: Does it make

a huge difference if each player’s using exactly the same instrument, or

if they’re all playing different ones to get the same result?

JF: There’s a lot

to be said for either approach. I find it interesting to still be able

to go to a country like France and hear one stylistic approach to the music.

There is a certain blend. Even if I may personally disagree, or feel

that it’s not my favorite approach, still, there’s a lot to be said for the

uniformity of approach to the instrument. It makes a very strong statement,

stylistically.

BD: If an American

orchestra has an opening or two in the bass section, should they try to make

everyone conform to one standard, or try to remake the section over years?

JF: I don’t think

it’s possible anymore in this country. I truly think one of the things

that drew me to the instrument was the possibilities that do exist, and the

availability to be creative with the instruments, to try new things and to

look for different approaches. It is the state of the art in America

today, and we could not go back to any other possibility at this point.

BD:

Tell me about your own instruments.

JF: I have a 1752

Joseph Stadlmann Viennese violone, and I have a G violone which is a reproduction

of an instrument by Ernst Busch, a German maker, in 1604. The reproduction

was made by a very, very talented maker now living in the United States,

an Englishman named John Pringle who works extensively in the instruments

of the gamba family. I also have the reproduction of the Nuremberg

instrument I mentioned before, and that was made by a gentleman named Dominic

Zuchowicz, a Canadian luthier.

BD: Is it the repertoire,

then, that makes the decision as to which instrument you play?

JF: Yes, absolutely.

It is the repertoire, the place and time that the repertoire was written,

which drives the choice of instrument.

BD: Are there times

that you need two different instruments in a single concert?

JF: Yes, that’s

come up fairly often. As you know, I’m particularly interested in early

music, and when music on the first half is programmed from the Baroque period

and the second half is of the Classical era, one goes back and forth a little

bit.

BD: That must be

a terrible burden on you to bring both instruments.

JF: [Laughs]

Well, it just demands a larger automobile.

BD: It’s a lot

different than bringing an A and a B-flat clarinet.

JF: Right.

But it’s all worth it. It’s great fun.

* *

* * *

BD: What advice

do you have for younger bass players coming along?

JF: The world of

possibilities continues to expand for the double bass. It’s just phenomenal!

I was actually in attendance at the first International Double Bass Society

Convention in 1968, and there was a gathering of a total of about forty people

in Madison, Wisconsin. It was headed up by Gary Karr, and there were

some very notable bassists — Fred Batchelder from the Philadelphia Orchestra,

Warren Benfield from the Chicago Symphony, Richard Davis who was a very famous

jazz bass player and now professor at the University of Wisconsin, Knut Guettler

from Norway... Sort of the grandfathers, now, of the modern bass movement

were all there. It was really an ear- and eye-opening experience.

BD: Was there an

immediate camaraderie amongst all the bassists?

JF: Oh, absolutely.

It was people who had been pursuing the same goals for many years coming together

and finding that they had friends, unbeknownst to them, who had been pursuing

similar things for years.

BD: [With mock

horror] “My god! I’m not alone!”

JF: [Laughs]

Exactly. But I bring that up because here it is 1997, and very talented

player and teacher, Paul Ellison, who teaches at Rice University, recently

held the umpteenth bi-annual convention, and there were, I guess, a couple

of thousand double bassists all in Houston for that convention, pursuing

everything from avant-garde jazz to early music, orchestral music, solo literature,

everything.

BD: Is it good

for someone to play both the old music and the new music, rather than specializing?

JF: There’s a lot

to be learned from both. I’m a strong advocate of doing both.

Having a historical perspective on performance techniques and styles gives

you greater flexibility, and you are more conscious of different possibilities

of articulation and approach no matter what style you are playing.

Similarly, a focus on some of the modern techniques and technical standards

is at a fairly high level. To bring that technical standard and excellence

to the early music is very beneficial, as well. So cross-pollination

is very helpful there.

BD: Do you do any

world premieres?

JF: I have.

BD: Is that satisfying?

JF: Oh, extremely.

As I mentioned, I was doing some work in Rome with William Ferris, and we

have had a very strong and good collaboration over the years. He has

written a number of chamber works and solo pieces for me, and I find working

with a composer like Bill opens another window into the creation of music.

Being part of actually birthing a piece is a very, very exciting thing to

do, and I would recommend that all musicians, all performers, seek out soul

mates who are composers and work with them because it really energizes both

the composer and the performer to work collaboratively and give birth to

something new.

BD: What should a composer know about the double

bass that is generally not known, before he writes the piece? It can

be assumed that the composer would know a great deal about the violin or

the piano, probably having played it or studied it, but not the double bass.

BD: What should a composer know about the double

bass that is generally not known, before he writes the piece? It can

be assumed that the composer would know a great deal about the violin or

the piano, probably having played it or studied it, but not the double bass.

JF It’s interesting,

because I’ve worked with a number of composers where the balance and volume

levels of the instrument surprised them. It’s a huge instrument, as

you noted, to lug around or look at, and sometimes composers think that because

it’s physically big it has a huge penetrating sound, which is not the case.

It is a physically big instrument, but it has a very warm, sensuous, luscious,

mellow sound, rather than a penetrating, piercing sound. So the issue

of balance with an orchestral accompaniment, in terms of concerto, or even

with the piano in a sonata setting can be a surprise to composers.

BD: Do you put

the piano lid down rather than have the lid up?

JF: Oh, that’s

very interesting, because merely closing the lid on the piano does not solve

the problem. It changes the whole overtone series of the piano sound,

so it merely dampens and acts as a mute, rather than really addressing the

underlying issue of the relative volumes of both instruments. The real

answer is where the composer places the accompanying figures in terms of

register on the piano or other instruments, and what tone colors are used

in an orchestra. Then it’s a matter of simply

staying out of the way of the solo line of the double bass.

BD: Should the

accompaniment stay at middle C and above most of the time?

JF: Right, which

plays tricks on the listener’s ear, because we’re all conditioned to listen

to the top of the register for the melody. So when the melody appears

in the bottom of the range, of the pitch register, and the accompaniment

is above, it can be disconcerting for an audience’s ears that aren’t prepared

for that experience. But this links it all back into the 16th and 17th

century, because as you well know, one of the most popular forms of music

in that era was the madrigal. In those, there was rarely just one melody

on top and everything else was the accompaniment. Each part was its

own separate melody that fit together with the harmonic structure.

That’s one of the reasons why I’m so drawn to early music, because each voice

has its own melody, and that’s certainly true of the bass part as well.

BD: Having sung

many madrigals earlier in my life, they are wonderful!

JF: There you go.

Unfortunately, what occurred in the 19th century was that much beautiful,

wonderful repertoire was written for the orchestra in that era, but it tended

to relegate the double bass into an instrument of what I call punctuation,

rhythmic or harmonic punctuation, as opposed to true melody. It was

an era that did not exploit all the possibilities, as the earlier era did,

or many compositions today do.

BD: Are you pleased

that the repertoire for the bass is expanding again these days?

JF: Oh, absolutely!

There are so many composers doing so many fine compositions.

BD: When you get

a composition handed to you, how do you decide yes, you will spend the time

learning it, or no, you will set it aside or send it to some other bass player?

JF: That’s a tough

one. If at all possible, I try and tackle it myself, and I think I

have done that with every piece. Oftentimes there is a very personal

component to the relationship that I want to honor, as well. For example,

after the birth of our first son, Ken, there came a knock on the door, and

an envelope was dropped off. I opened it up, and there was a beautiful

lullaby for double bass and piano written by William Ferris. How could

I not work on that? How could I not play that? It was an absolutely

beautiful piece that, again, birthed another piece of art here.

BD: Let me turn

the question on its head a little bit. Is there any reason that someone

should write today for the older instruments?

JF: My answer is

absolutely, and the reason I say that is the older instruments represent

a whole spectrum of sound possibilities that simply can’t be exploited by

the instruments of today.

BD: More colors?

JF: Different colors.

One of my favorite authors is Stephen J. Gould, the anthropologist at Harvard.

One of his main theories is that the world is not necessarily always progressive,

and I feel that’s certainly true in the world of music. It is different.

What is being composed today is wonderful in its way. What was happening

in 1835 was wonderful in its way, and all the way back. But I certainly

do not ascribe to the belief that some hold, which is that what was happening

in the 18th century was a progression over what happened in the 17th, and

everything just marches in one forward direction.

BD: Yet the antithesis

of progression is not necessarily regression.

JF: Exactly!

That’s exactly correct. Each age has its own beauty, and the instruments

of the earlier times have a very special beauty which deserves to be explored

by people living now, both performers and composers.

* *

* * *

BD: You’ve played

in the bass section of a couple of orchestras. Is that also satisfying?

JF: Yes, in its

own way. It proved not to be ultimately satisfying for me, only because

I like to be very self-determined and creative, and develop my own visions

with the music. That’s why I love chamber music, particularly.

I can have a true strong voice, an impact on what the result is. Orchestras

that I’ve played with, both here and in Europe, have been marvelous experiences,

but I wanted more than that as well. I find the chamber music collaborations

probably the most satisfying.

BD: Let me ask

a real easy question. What’s the purpose of music?

JF:

[Thinks for a moment] For me it’s multilayered, certainly. At

the top it’s physical, it’s sensuous, it’s in all of our senses, and it’s

aural. In fact one of the reasons I was really attracted to early music

is the feel of the gut strings under the hand, the mellowness and the sound

of it. So it’s satisfying in all of those dimensions, yet it connects

on another level, a deeper level. It connects me with other human beings

— not only those of us around today, but that humanity that has

always been there, that transcendent humanity of composers composing in another

place and another time.

JF:

[Thinks for a moment] For me it’s multilayered, certainly. At

the top it’s physical, it’s sensuous, it’s in all of our senses, and it’s

aural. In fact one of the reasons I was really attracted to early music

is the feel of the gut strings under the hand, the mellowness and the sound

of it. So it’s satisfying in all of those dimensions, yet it connects

on another level, a deeper level. It connects me with other human beings

— not only those of us around today, but that humanity that has

always been there, that transcendent humanity of composers composing in another

place and another time.

BD: Do you feel

connected to the old performers, too?

JF: I think so,

yes, especially because another part of early music that I find so attractive

and important is to work with the music, with the editions that were printed

in the time of the composers and the players of this early music, and to

see how they wrote down that music. Again, it’s another connection

to our humanness. Then, at its deepest level, it’s a very spiritual

activity for me. It has its religious aspects.

BD: We worship

at the altar of music?

JF: Yes.

BD: When you’re

playing the instrument, are you simply playing this piece of wood, or does

it actually become part of you so that it’s more your extension?

JF: I think of

it as an extension. Actually it’s like dancing with a wonderful woman

who’s a great dancer. It’s part of you. It is something different,

but it is part of you at the same time. There’s a lot of choreography

and dance-like aspects to playing the bass, so that’s another connection

to the maker of the bass who may have come from a different era, or the maker

today who’s making reproduction.

BD: Does your wife

ever get jealous of the instrument?

JF: [With a big

smile] Oh, I don’t think so. She started out as a musician herself,

a wonderful violist, so I think she understands.

BD: Do you ever

get to play together?

JF: Not anymore.

She has not played a viola for a long time, having given that up for three

marvelous children and a lot of computers. [Laughs]

BD: Now you can

have your own in-house quintet!

JF: Right.

There you go.

BD: Are you pleased

with where you are at this point in your career?

JF: Oh, there’s

always more that one wishes one could do and could have done. That’s

probably always going to be true. At the same time, I do have a certain

amount of satisfaction of having had the privilege to explore the music of

many different periods and many different places with very wonderful people

and great musicians. I feel very privileged for that, and in that sense,

it’s very satisfying.

BD: Does it take

a very special person to play the double bass?

JF: It’s not for

everyone. You can imagine someone drawn to the trumpet may not be drawn

to the double bass. In an orchestral setting, it’s an instrument where

you’re most noticed if you’re doing something wrong. [Both laugh]

BD: Piano subito is the time when the obscure

orchestral player becomes soloist.

JF: Yes, exactly,

and that’s one of the main reasons, ultimately, that orchestral playing wasn’t

for me, full-time. But that’s part of what a double bass does.

It is that blend and fitting into the whole, but still being extremely important,

although maybe not blatantly so. We’re a little

bit behind the scenes because the bass, so often, at least in an orchestral

setting, will set the harmony. It’s the harmonic anchor of everything

else that’s going on, and many times it’s the rhythmic

pulse of the entire ensemble as well.

BD: Most music

has the melody on top and the harmony on the bottom, and everything else

is fill.

JF: Yes.

[Laughs] So without the bass, everything would be truly lost.

But that point may not be always obvious.

*

* * *

*

BD: Do you play standing or sitting?

JF: I play standing.

I find that gives me the most freedom, physically, to move with the instrument.

But every bass player approaches that a little differently, and as we talked

about there are many approaches, many right approaches. There are some

marvelous bass players who sit, but my preference happens to be to stand.

BD:

When you come to a new concert venue, do you look for a good place to stick

that end pin?

JF: [Laughs]

Oh, yes! Just finding a place sometimes can be a challenge, and it’s

always interesting. Some people are a little more fastidious than the

bass players about where they’ll allow this to happen.

BD: You don’t want

to put it in the middle of an expensive Oriental rug.

JF: Exactly, so

we need to be sensitive to our surroundings in many ways.

BD: Do you carry

a little coaster?

JF: Yes, and also

I have been known to remove my belt to put it around the end pin and fasten

it to my foot, so it won’t slip away from me in a slippery situation.

BD: I’ve seen bass

players moving their instrument on a little wheel.

JF: I’ve got a

little wheel for long walking trips between a concert hall and rehearsal

place. Sometimes that comes in really handy... another marvel of modern

technology! [Both laugh]

JF: You’ve made

three solo recordings. Do you play the same for the microphone as you

do for the audience?

JF: It is different.

I do find in a recording situation that it’s more difficult because there’s

not a real live audience there to react with. So for me, that’s a little

more difficult. I thrive on that interaction with audience, but both,

I think, are very important ways of performing. The discipline of recording

is extremely helpful for technique, and trying to get it on tape the way

you really want it. That’s always a challenge. The

whole world of recording a double bass is a very interesting study in science

in itself.

BD: Have you ever

thought of maybe putting a little screen or solid wood behind you, just to

focus the sound out?

JF: Actually that

works very well. What we found is that a lot of the sound of a double

bass actually emanates from the back of the instrument, that large, vibrating

back. So I really like to have a closer microphone near the F hole

of the instrument up and away in front of the instrument, and others three

or four or five feet in back of the instrument. This is another reason

why I like to stand rather than sit, so that the back can be completely free

to vibrate. I think it’s an interesting acoustical property of the

instrument.

BD: Are you pleased

with the records that have come out so far?

JF: Oh, you always

wish you could do things differently. So it’s the same idea as the

answer that I had before in terms of overall career. Certainly there

are things that I would like to do differently — better

— but I’ve come to say it chronicles me at that point in time

and space.

BD: I haven’t met

one musician yet that hasn’t said, “Oh, but it could be better!” [Laughs]

JF: Better, yes,

yes. It always can be better.

BD: Is there such

a thing as a perfect performance?

JF: I have never

achieved it.

BD: Does it exist?

JF: Boy, I’ve heard

some performances by others where it so moved me that I felt that came pretty

darn close, if not being there. But then it’s interesting... you go

backstage and talk to the performer, and they’re saying, “Oh, it could have

been so much better! I really wanted to do this...” [Both laugh]

So I guess it’s in the ear of the beholder whether that phenomenon truly

exists or not.

BD:

But in the end it’s all worth it.

JF: It’s all worth

it. No question.

BD: Thank you for

all the music that you’ve given us so far.

JF: Thank you very

much for keeping it all going. I appreciate that.

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Evanston, Illinois, on June 30,

1997. Portions were broadcast on WNIB six weeks later. This transcription

was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website,

click here. To

read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few

other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce

Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until its

final moment as a classical station in February

of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in

various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now

continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his

website for more information

about his work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a full list of his

guests. He would also like to call your attention

to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

Jerry Fuller began studying the double bass at age 16 and was invited to

join the Lyric Opera of Chicago orchestra three years later. Within two years

he was promoted to first desk of the double bass section in addition to performing

with the Santa Fe Opera. Mr Fuller has also served as solo double bass of

The Musikkollegium Winterthur Switzerland. While in Europe, Mr. Fuller became

interested in historically-informed performance practice and has achieved

international recognition for his work with period instruments. A Chicago

Artists Abroad grant recipient, Mr.Fuller’s performances in London, Rome,

Geneva and Edinburgh have been broadcast worldwide. In addition, Mr. Fuller

has performed at the Ravinia and the Aspen Music Festivals and both the Boston

and Berkeley Early Music Festivals.

Jerry Fuller began studying the double bass at age 16 and was invited to

join the Lyric Opera of Chicago orchestra three years later. Within two years

he was promoted to first desk of the double bass section in addition to performing

with the Santa Fe Opera. Mr Fuller has also served as solo double bass of

The Musikkollegium Winterthur Switzerland. While in Europe, Mr. Fuller became

interested in historically-informed performance practice and has achieved

international recognition for his work with period instruments. A Chicago

Artists Abroad grant recipient, Mr.Fuller’s performances in London, Rome,

Geneva and Edinburgh have been broadcast worldwide. In addition, Mr. Fuller

has performed at the Ravinia and the Aspen Music Festivals and both the Boston

and Berkeley Early Music Festivals. In the name of full disclosure, I am happy

to report that Jerry Fuller is a long-standing friend of mine... and it was

not until I just typed that sentence that I realized the phrase ‘long-standing’

also applies to his position with his chosen instruments! Indeed, we

talk about that later in the interview.

In the name of full disclosure, I am happy

to report that Jerry Fuller is a long-standing friend of mine... and it was

not until I just typed that sentence that I realized the phrase ‘long-standing’

also applies to his position with his chosen instruments! Indeed, we

talk about that later in the interview.

BD

BD