|

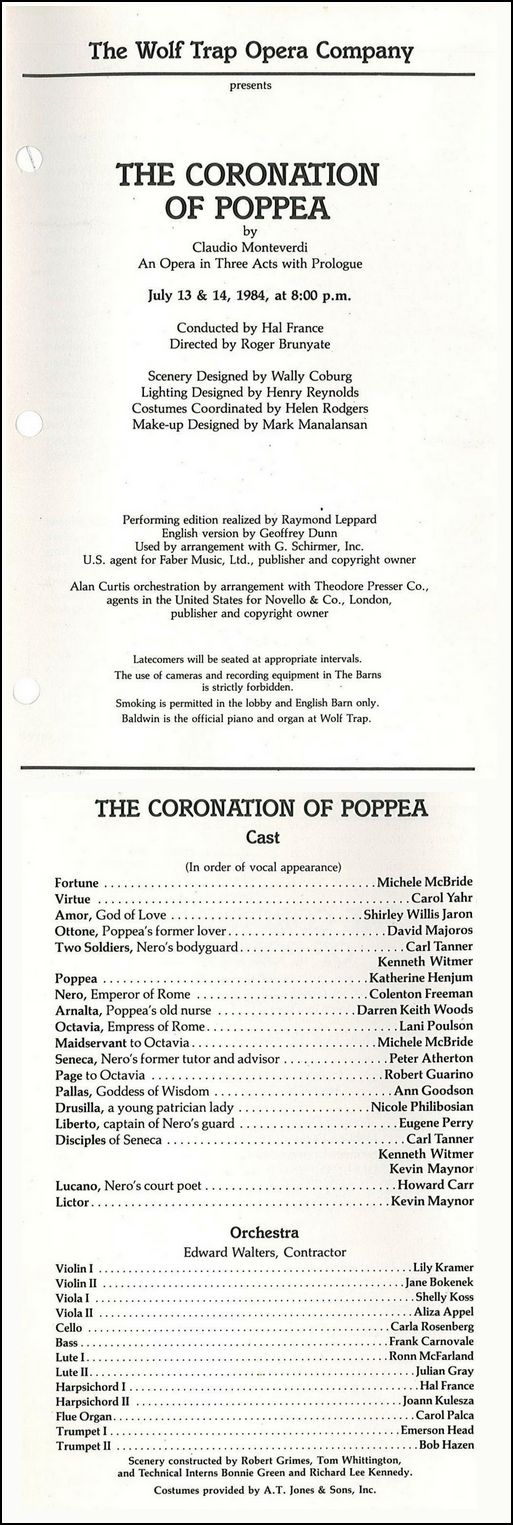

During a thirty five-year professional career as an opera conductor,

Hal France has led organizations and performed with opera companies

and symphony orchestras around the United States. While conducting throughout

the United States and abroad his activities include speaking and advocating

for arts education. He has completed tenures as Executive Director of

KANEKO (2008–2012), Artistic Director of Opera Omaha (1995–2005), and

Music Director of the Orlando Philharmonic (1999-2006). He served

as an Adjunct Professor at the UNO School of Music from 2007-2016.

Mr. France has collaborated with many of this country’s opera companies.

In 1981, he made his professional debut at Washington’s Kennedy Center. He

served the Houston Grand Opera first as Associate Conductor and later

as Resident Conductor over a four-year span. He has conducted performances

for the New York City Opera, Seattle Opera, Florida Grand Opera, Opera

Theatre of Saint Louis, Santa Fe Opera, Glimmerglass Opera, Opera Company

of Philadelphia, Lyric Opera of Kansas City, Chautauqua Opera, Minnesota

Opera, Cleveland Opera, Opera Carolina, Wolf Trap Opera, Opera Festival

of New Jersey, Tulsa Opera, Portland Opera, Kentucky Opera, and Orlando

Opera.

He has guest conducted the Royal Philharmonic, the National Symphony,

the New Jersey Symphony, the Richmond Symphony and the Jacksonville

Symphony. In 1992, he made his European opera debut with the Royal

Opera of Stockholm with a production of Maria Stuarda.

Hal France has been involved in numerous community collaborations

that include:

- BlueBarn Music Festival

- Habitat for Humanity Omaha’s Multi-Faith

Music Festival

- National Hunger Awareness Day Convocation

- Why Arts

- Omaha Performing Arts 1200 Series Young

Artist Nights

- Kountze Memorial Lutheran Food Pantry

He served as the first Executive Director of KANEKO a non-profit

organization founded by the artist Jun Kaneko and his wife Ree in Omaha,

Nebraska. During a four-year tenure he was integrally involved in every

aspect of the organization’s creativity based programming and infrastructure.

He promoted and helped design an extensive number of community partnerships,

the Great Minds Lecture series, performances, exhibitions, workshops

and educational outreach programs that brought people into a forum of

ideas and collaboration.

Mr. France served as Music Director of the Mobile Opera and Lake

George Opera Festival and as Music Director of Opera Omaha before

assuming the position of Artistic Director. He has been on the

music staffs of the Glyndebourne Festival, Aspen Festival and the Netherlands

Opera. He has degrees from Northwestern University and the University

of Cincinnati College Conservatory of Music and a fellowship from the

Juilliard Opera Center. Recently he received an honorary

doctorate from the University of Nebraska at Omaha and an Admiralty

in the Nebraska Navy from the Governor of the state.

Recent Activity (Selected Highlights)

- Pianist, Vespers Music: Recital Performance

with Taylor Stayton.

- Pianist and Music Director, Performance of students from Speed

Dating with Sound Health, Buffett Cancer Center, UNMC.

- Musician and Speaker, Food for the Soul Series, Omaha Conservatory

of Music

- Guest Conductor/Instructor Hansel and Gretel opera performances,

Depaul University.

- Music Director, Indecent, BLUEBARN Theatre.

- Pianist, International Vocal Health Day Performances, Buffett

Cancer Center, UNMC.

- Performer, Chamber Music, Crossroad Music Festival

== From the website of the University of Nebraska

Omaha

--- --- --- --- ---

--- --- --- ---

Hal France is a sought after guest conductor of opera throughout

the U.S.A. He has conducted nine productions for the Houston Grand

Opera, eight productions for Central City Opera (Show Boat,

La Fanciulla del West, L’Italiana in Algeri, Gloriana,

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Gian

Carlo Menotti's The Saint of Bleeker Street, Candide, and Carlisle Floyd's Susannah),

four productions for Opera Theater of St. Louis (including the world

premiere of Stephen Oliver's Beauty and the Beast), five productions

for Kentucky Opera, three productions each for the New York City Opera

(Oliver Knussen's Where

the Wild Things Are, The Ballad of Baby Doe, and the world

premiere of Ezra Laderman's

Marilyn) and Orlando Opera (Macbeth, The Merry Widow

and Il Barbiere di Siviglia), and two productions each for

Cleveland Opera (Tosca and Rigoletto), Madison Opera

(La Boheme and The Magic Flute), Calgary Opera

(Tosca and The Ballad of Baby Doe), and

Utah Opera (Lucia di Lammermoor and Romeo et Juliette).

Mr. France has served as Artistic Director of Opera Omaha, as Music

Director of the Orlando Philharmonic, as Resident and Associate Conductor

for the Houston Grand Opera, Music Director of the Mobile Opera, Lake

George Opera Festival, and as Music Director of Opera Omaha before assuming

the position of Artistic Director. He was also Music Director of the

Orlando Philharmonic. Early in his career, he served on the music staffs

of the Glyndebourne Festival, Aspen Festival, and the Netherlands Opera.

He began his professional career as assistant to John DeMain at the

Houston Grand Opera.

Elsewhere, he has conducted productions for Seattle Opera and Florida

Grand Opera (Floyd's The Passion of Jonathan Wade), Minnesota

Opera (Madama Butterfly), Opera Company of Philadelphia (The

Rake’s Progress), Santa Fe Opera (Ingvar Lidholm's A Dream Play

- world premiere), Portland Opera (Tosca), Chautauqua Opera,

Glimmerglass Opera (Iolanthe), Tulsa Opera (Don Pasquale),

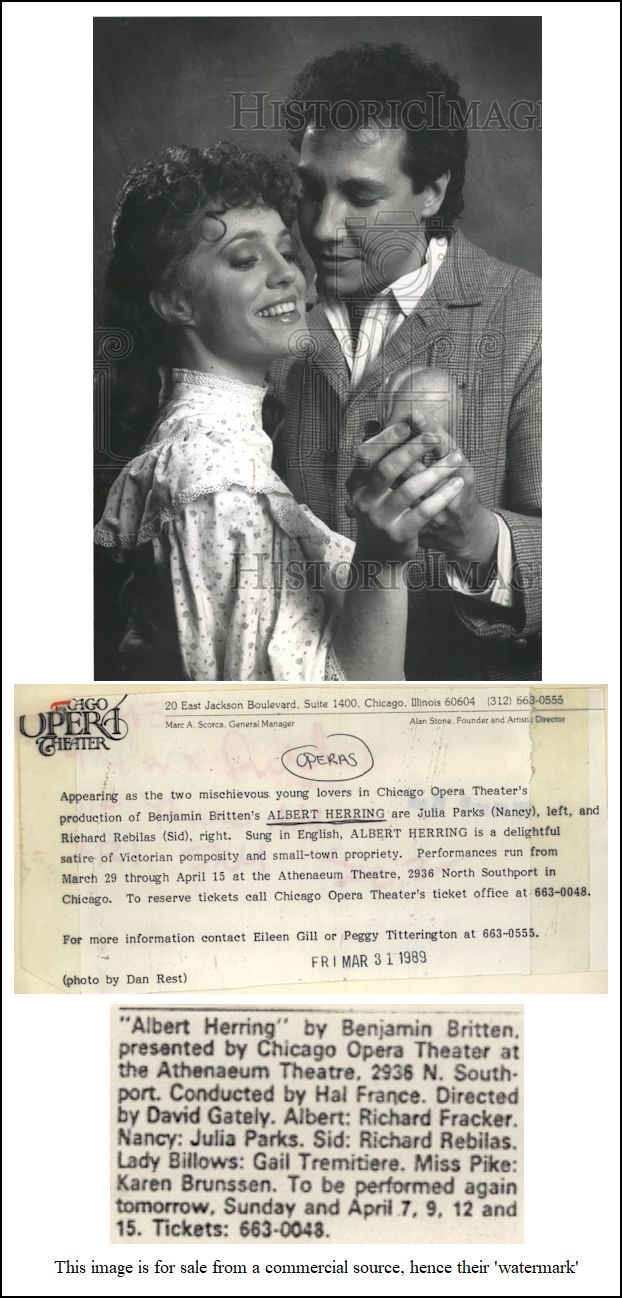

Opera Carolina, Chicago Opera Theater, Wolf Trap Opera, Opera Festival

of New Jersey, Lyric Opera of Kansas City, Hawaii Opera Theater,, Arkansas

Opera Theater, Mobile Opera, the Manhattan School of Music (Street

Scene), and Ricky Ian Gordon's The Grapes of Wrath. In Europe,

he has conducted Maria Stuarda with the Royal Opera in

Stockholm.

Recent engagements include productions of Bluebeard’s Castle

and Falstaff for Opera Omaha, Macbeth for

Chautauqua Opera, Rigoletto, Carmina Burana and I

Pagliacci and The Magic Flute for Hawaii Opera, Man

of La Mancha for Utah Opera, Mark Adamo's Little

Women for Northwestern University, Show Boat plus a

double-bill of works by David Lang for Portland Opera, and The Pirates

of Penzance for Lyric Opera of Kansas City.

On the concert stage, he has conducted the Richmond Symphony, Orlando

Philharmonic, Nebraska Festival Orchestra and Jacksonville Symphony

in subscription concerts, and the Chautauqua Festival Orchestra, Juilliard

Symphony, and St. Louis Symphony in special galas

== From the website of Pinnacle Arts Management

(with additions)

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my

interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

Walter Felsenstein (30 May 1901 – 8 October 1975) was an Austrian

theater and opera director. He was one of the most important

exponents of textual accuracy, and gave productions in which dramatic

and musical values were exquisitely researched and balanced. In

1947 he created the Komische Oper in East Berlin, where he worked as

director until his death.

Walter Felsenstein (30 May 1901 – 8 October 1975) was an Austrian

theater and opera director. He was one of the most important

exponents of textual accuracy, and gave productions in which dramatic

and musical values were exquisitely researched and balanced. In

1947 he created the Komische Oper in East Berlin, where he worked as

director until his death.