The Composer in Conversation with Bruce Duffie

As an old radio man, the first thing is to get the pronunciation right! I always asked my guests, and usually found I'd been doing it correctly. Brian Fennelly is spoken BREE-uhn FEHN-uh-lee.

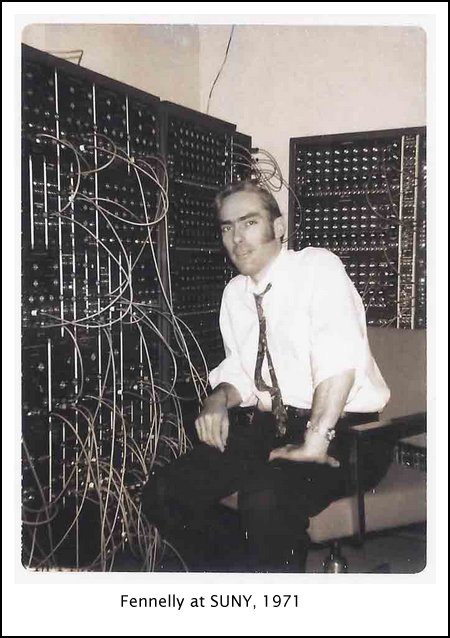

He was born in 1937, and studied at Yale, earning a M. Mus in 1965 and his Ph.D in 1968. That year, he joined the Faculty of Arts and Science at New York University, where he stayed for nearly 30 years before retiring (early) as Professor of Music in 1997. Besides the teaching and composing, he performed on the keyboard and has seen several recordings of his efforts remain in the current catalogue, with an Albany CD of five orchestral works due out soon.

On one of his final leaves from NYU, he swung through Chicago in

April of 1995 and we'd arranged to meet for a chat. As a guest in

my home, he was affable and cordial, as well as speaking openly and

freely

about our favorite subject. Here is much of what transpired that

afternoon.....

Bruce Duffie: You're both composer and teacher. How do you divide you time between those two taxing activities?

Brian Fennelly: When I'm teaching, it consumes most of my energy because I tend to be concentrated on things that I'm doing, things that have to be done, things that I'd like to bring to students' attention, as well as catching up on whatever reading I need to in order to feel secure and be authoritative on whatever the subject that I might be involved in.

BD: What are the various subjects that you teach - besides composition?

BF: Composition, which doesn't require a lot of practice - you just have to keep adept at reading scores and knowing how to steer students to their best advantage and know how to challenge them. Essentially you have to be a devil's advocate, asking "What did you mean by this," and so forth. The better a composer can explain that, then the more secure they are in what they know they want to do. And if they don't, it starts them thinking about it. Other courses include History of Music Theory, which I taught last semester for the first time in 12 years. A few things have happened since then, especially in various journals, so I had to spend some time catching up. Certainly the basics of 20th Century theory was still the same, but there was a lot of investigation that had gone on and further writings and translations of some rather difficult texts.

BD: Is it a bit like science, wherein everything up to today stays the same, but you have to keep up with today and tomorrow?

BF: Yes, you do. Science is not absolute, and the problem with music theory is that it's generally someone's opinion about things, and those things always reflect the matter of the times. Things vary as to what happens to be in prominence. Back when I first became involved with music theory as a student, Schenker was taught in very few schools in this country, mainly by people who had training in Europe and who had trained other people. Now you can get it at practically any school, but it's taught in so many different ways that it tends to reflect the scattering of Schenkerian thought. So there's a thinning out of the ideas and their applications.

BD: Is that a good thing, a bad thing, or just a thing?

BF: It's a thing, yes. To certain people who would want to maintain an old-line way of thinking and view this as spreading it upon the waters in a very cavalier manner, of course it's a bad thing. But I certainly enjoy following the field.

BD: You keep up with all the latest techniques in history and theory, but do you put those into practice when you're actually putting pen to paper for your own original compositions?

BF: That's an interesting question because obviously when you study a score of a composer that you respect, there may be something new and different in that which may suggest to you thoughts you might like to follow up on. I can only say that back when I first studied some rather avant-guard scores, I might start to think about the kind of pieces I might write should I start to employ some of those techniques. When it came to writing a piece, I rarely did use those, but they were certainly part of the baggage we carry and what was available. I've dabbled a little bit in what would be called ‘controlled chance' but I'm certainly not a chance composer. I tend to relegate things like that for textural purposes. It could be composed out, but it's a lot simpler just to let it fly and let things happen in a rather informal manner, and it will still produce the same result, and maybe even better that I could write. But it would not be the primary focus of the piece or the passage or anything else. It would be accompanimental or in the background.

BD: With all of your teaching load, do you get enough time to compose?

BF:

Since I'm on leave this semester, I should, but it seems like I've been

traveling into New York for concerts to manage and doctoral exams to be

on the committee for. I'm reading a dissertation right now that I

brought with me to Chicago. And since I still do a little playing

in public, I must practice a bit. These things do get in the way

at times, but when I really set my mind to it, I think I can get things

accomplished fairly efficiently. But I do need segments of time

for

that. It's nice to have either a summer or a leave to be able to

devote one's time more fully to it.

BF:

Since I'm on leave this semester, I should, but it seems like I've been

traveling into New York for concerts to manage and doctoral exams to be

on the committee for. I'm reading a dissertation right now that I

brought with me to Chicago. And since I still do a little playing

in public, I must practice a bit. These things do get in the way

at times, but when I really set my mind to it, I think I can get things

accomplished fairly efficiently. But I do need segments of time

for

that. It's nice to have either a summer or a leave to be able to

devote one's time more fully to it.

BD: If you suddenly won the New York State Lottery and never had to hunt for dollars, would your music sound any different than it does now?

BF: No, but I've never bought a lottery ticket! So I can't win it, but no, I don't think my music would change. I think it would give a person financial freedom, not that I would want to stop teaching, but I would take a leave whenever I wanted to, rather than when it was a paid leave. It would also allow a person to be a little more secure in the promotion of the works and so on. So much of that tends to fall upon the artist these days.

BD: You would go out and make sure that performances get done?

BF: You would hire a publicity person, although for composers they're fairly ineffective. I've never done it, but I know others who have and have felt that way. I think what you might do is have a certain focused program of lines of attack, and get administrative help to use the computer to type letters or make contacts. You'd be in a better position to organize recordings. That does take a bit of work and a bit of money, too.

* * * * *

BD: Coming back to composition now, you work on pieces when you get the chance. Do you work on more than one at a time or focus all of your creative attention on one specific piece?

BF: It's usually one at a time. I may put it aside to do a second piece, but I never work on the two at the same time.

BD: But when you're working on one piece, if you get an idea that you know would work in another, do you stash it away?

BF: Yes! Exactly! That has happened. In the piece that the Louisville Orchestra recorded, I wrote the work and did another before orchestrating it. And when I orchestrate a work, I also revise, so that was a piece which was set aside. In the last few years, I've been working on some movements that will be put together and called A Thoreau Symphony. It reflects my particular dedication to Thoreau and his ideas, and I've done other pieces in that light, but this was supposed to be a compilation of three independent pieces to be grouped together. I'd done two and while working on something else, I jotted something down that became the beginning of the third piece. It could easily have been tossed away, but it did become part of that work.

BD: When you're working on a piece and you're tinkering with it, how do you know when you're finished?

BF: That's interesting. Usually you have a concept of the time-frame you're working in. Stravinsky wanted to know to the second how long a particular thing should be. I never worked that way, but on one piece I kept a log. I wanted to write a ten-minute piece and I was keeping track of the advance of the piece and the proportions of it, so I did sort of compose it out in a fashion that was somewhat pre-determined at least in terms of the sections within. Usually, it's a much more informal affair. I usually start at the beginning, though not necessarily, and I might skip over a section that I didn't have a full idea of how to develop. But usually it goes right from the beginning to the end. It might be revised later on, but it's more or less set at that point.

BD: But it doesn't come out fully formed. You have to work with it, don't you?

BF: You work very hard with it. Sometimes you throw some things out and you might have to start again because that's not what I had wanted to produce. For me, it sometimes seems very slow. I know there are times when I've been able to write very quickly, but other times when I only produce four measures in a week. Those four measures may have been very hard to realize because of the particular challenges I set up for myself in the progress of the piece. What's always interesting is to compose those things that are going from one place to another - the transitions, shall we say - because they're not transitions in the usual (19th Century) idea of modulation. They might involve overlapping speeds so the point of arrival might be a new tempo, but I don't want anybody to know that it's coming until we're already there and have been in it for some time. We got there in a rather subtle way and the problem in composing that is that the concept is fine and perhaps you can hear the music fairly well, but to notate it is the problem. In an orchestral piece, you have to be practical. You can't ask the violin section to make some very strange rhythmic subdivision because you only have a certain amount of rehearsal time - at least in this country.

BD: You say you don't want the public to know where you're going until you're there. What about repeated hearings?

BF: That's the next level of hearing. It's just that it's not predictable necessarily. You don't know that the ‘modulation' is happening, but you know that something is in flux. Something from the old is being obscured and the new idea is coming into focus and the exact point where one goes out and the other comes in is not so obvious. As you say, repeated hearings can allow you to come to grips with that and take a little more interest in how those things are realized.

BD: Are you very conscious of the audience that will be listening to the piece when you're sitting at your desk and making little marks on the page?

BF: It's interesting. I just had a communication with a composer who writes two kinds of music. One is chamber music with aleatoric elements and the other is audience-music which has tunes and everything else. He knows which audience will be listening and he's very successful at it. I know we all have different faces. I've written a ragtime piece and it's the only piece of mine for a number of years that has a key signature. I like it and it has the same kind of compositional integrity to it that I try to bring to all my other music. So it's part of the same family, but it wears different clothes. It was an accident... I was asked to write a piece for the Empire Brass Quintet and I'd heard them do some Joplin rags (which I thought they'd done beautifully) and I just couldn't get started on this other piece. So I started writing a rag just to get the juices flowing. It started out as a lark, but I worked on it for a week and then went to something else.

BD: You're obviously aware of how long a piece will take to perform. Are you aware, before you start, how long it will take to complete the compositional process?

BF: No. We always think we're leaving enough time, and I don't like to have a deadline which states it must be ready by such-and-such a time. I don't want to do anything less that best that I can possibly do, and if there's something that interferes with it and I can't make the deadline, then what am I going to do? Should I accept something less? On the other hand, having a deadline is good because then that tells you that you absolutely must do it and you cannot waste your time. So there's the good and the bad to it. I was asked by my Alma Mater to do a piece for chorus organ and brass for the bicentennial of the college, which was (then) only three months away. They needed the score and parts and everything, so I put everything else aside for it and enjoyed doing it.

BD: It was obviously very close to your heart. But when you get an offer, how do you decide whether to accept it or turn it down?

BF: It has to be attractive in some way. It might be the instrumentation or the person who will play it. Perhaps it was something I had in mind anyway. Is it something new for me? Is it an instrument I know how to write for? It's fine to take on a challenge, but I might not be ready for it at the time.

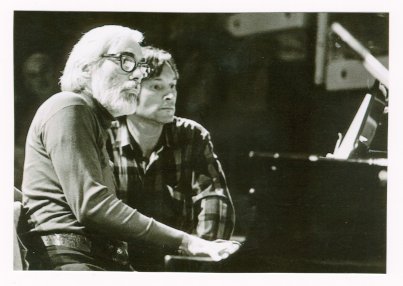

Brian Fennelly with Zygmunt Krauze performing with

the

Warsaw Music Workshop at the ISCM World Music Days

(Brussels, 1981)

BD: When you get an offer or just an idea for a piece, is it your responsibility to make sure the performer can play the notes, or is it the performer's job to get your notation into proper sound?

BF: I think it would be improper for a composer just to write anything and expect the person to play it. There have to be certain boundaries. If it's for an instrument I don't know well, I've always found it helpful to collaborate and bounce some ideas off the player, and if something isn't playable, I want to be able to re-think the passage in some way. I still know very little about the saxophone, but have written three works for it because of my friendship with the player and his family. There have been pieces I've taken to players and have revised certain passages that I thought were playable. Any of us can get hold of the usual string instruments, but sometimes it's a matter of moving the hands from one place to another and just how securely it can be done. My ambitions can be a little bit too high to be practical.

BD: Assuming that the technical ability of players continues to progress, should you perhaps make an alternative passage to be kept until a player is able to make it sound as you originally envisioned?

BF: If it's possible, yeah. For example, the saxophone has an altissimo register which can be exploited, but I've used it rather sparingly. I'd like the piece played by more than just the top two or three players in the world. You have to provide an alternative line sometimes, but the preferable one is in the large notes. There are times when I've written very difficult rhythmic things because I was trying to realize a vision that I know is playable, but at the speed I was asking, it's not something you could sight-read. So I would re-notate it in a more regular fashion even though it was more awkward, but I'd provide the alternate notation so the person could learn that sort of thing.

BD: I'm told that Fritz Reiner re-notated Stravinsky so that the beat-pattern would not have to change, but now there is no need for such a help.

BF: That's right. But I think it is presumptuous for a composer to expect that every note should be played. There are composers who have written impossible pieces, and they know they're impossible. There's a cello piece by Xenakis which has a passage that ascends and descends simultaneously. It's impossible to play it that way, but there is a recording which manages it by mixing two tracks of the same player. Xenakis knew it was impossible and the challenge of the player was to somehow realize the intention of the music and approach it as best as one could. [See my Intrerview with Xenakis.]

BD: Then which is the real piece - the attempt that one player can do, or the flat plastic where all the notes are actually there?

BF: But you don't know it unless you've seen the score, and having seen it, you know that it's impossible. I think the real piece exists in the live performance where you see the performer grappling with the impossibility of the situation. I try to keep things within practical limits, but I know I've written some awkward passages even for the piano. I figure why not write it that way because compositionally that was what I wanted to hear. So there are challenges, but not ones that continue throughout an entire piece.

BD: Do you write it to be difficult, or simply because that is what it has to say?

BF: That's what it has to say, although part of the piece you're trying to project might be virtuosic playing, in which case it becomes part of the piece. An étude is a study in something, so that becomes part of the challenge of the piece and is what the composer has to put into it.

* * * * *

BD: I made an assumption earlier that the technical ability of the performer is getting better. Is that assumption correct?

BF: I believe so, at least in what we've experienced in the last 20 years.

BD: Then is the musical ability of both performer and audience also getting better as we go forward in time?

BF: The audience progresses, though it seems to be static these days. But there has to be limit to what performers can play.

BD: Why?

BF: As Ralph Shapey used to say, they're on the instrument. Well, maybe they just aren't on the instrument and you just can't possibly write them.

BD: They abandoned Tristan und Isolde after dozens of rehearsals, and now any opera house can at least get through the score.

BF: I heard a very local German opera house do Moses and Aron and that's a very difficult score to get through. But everything is within practical playing limits.

BD: But that's technical. Let's move on to the ‘musical' ability. Is the musicianship that you've experienced progressing year by year?

BF: I think young people seem to catch ideas and are able to come up with their own about how things are constructed and how relationships might be made. They may not be the ones that composer has thought of, but they might be perfectly logical and viable ways to deal with the piece. There are people who have developed these instincts and by studying the repertoire are able to grasp things that were very hard 20 years ago. So we are progressing in that sense.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of musical performance?

BF: I think so. I was at a master class at Juilliard where the American Brass Quintet was playing a new piece of mine, and it was difficult because I wrote it to be challenging to them. There are players who will only play pieces that are challenging. They like it because once they've realized it, they feel good about the piece and good about themselves and want to play the piece many times. So in this class, with all those young people who were top-notch brass players, they heard the piece played and it should fire their enthusiasm to replicate it and even make the next leap. To realize that is very heartening. That's a special audience, of course. They were going to take on the tradition. I felt very optimistic about their participation.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of musical composition?

BF: It will certainly go on and we'll see various trends that will come and go. We never know what the next turn is going to be. There is so much involved with technology these days. I've been impressed with things I've seen done with computers. I've never been involved with them myself, having gotten out of electronic music when it became automated and became the realm of those who could do interesting circuit-patching rather than those who have real compositional ideas. I've been disappointed by a lot of computer music I've heard, but I've been encouraged by other things, and I don't think it's any different than instrumental music or vocal music or opera or whatever else you're going to encounter. Some you'll find intriguing and a lot you'll not want to hear again. And there are some things that you may have enjoyed hearing that one time and not want to go back to. We felt they were very effective for what they were and they made wonderful audience pieces, but when you're a composer, you're a different kind of audience. It's like watching a movie or TV show and hearing the music come in underneath. Being a musician, you know what the music is doing to the scene and you know how much it contributes to it at that point. However the person making the movie thinks that the people will just be involved in the experience and not be listening to the different levels that went into the score.

BD: It's obvious what the purpose of music behind a film would be. What is the purpose of purely abstract concert music?

BF:

Since it is abstract, the purpose is to be an expression of some idea

that

composer wants to realize, and we would hope in this day that it isn't

just a rehash of everything else. There are things that can be

re-written

very professionally and sound marvelous, but I think we'd like to be

challenged.

I think composers like to be challenged. I don't think audiences

like to be challenged, but composers like to be and when they hear

pieces,

they like to think that the (other) composer is meeting some challenge,

too. It may be a very simple idea and it may be a very appealing,

audience-attractive piece. If it is done in a successful way and

there is a challenge that is met, I applaud the composer. I can

feel

very happy for somebody who has accomplished that sort of thing.

For my own taste, I don't have narrow limits. I can listen to a

lot

of different kinds of musics. If there's a minimalist piece that

works wonderfully, I'm very happy for the composer. I don't write

that kind of music. I've had students that are involved with it

and

I can certainly say that I didn't tell them how to write it, but I make

observations and that's what they were looking for at that point.

BF:

Since it is abstract, the purpose is to be an expression of some idea

that

composer wants to realize, and we would hope in this day that it isn't

just a rehash of everything else. There are things that can be

re-written

very professionally and sound marvelous, but I think we'd like to be

challenged.

I think composers like to be challenged. I don't think audiences

like to be challenged, but composers like to be and when they hear

pieces,

they like to think that the (other) composer is meeting some challenge,

too. It may be a very simple idea and it may be a very appealing,

audience-attractive piece. If it is done in a successful way and

there is a challenge that is met, I applaud the composer. I can

feel

very happy for somebody who has accomplished that sort of thing.

For my own taste, I don't have narrow limits. I can listen to a

lot

of different kinds of musics. If there's a minimalist piece that

works wonderfully, I'm very happy for the composer. I don't write

that kind of music. I've had students that are involved with it

and

I can certainly say that I didn't tell them how to write it, but I make

observations and that's what they were looking for at that point.

BD: When you hear one of your own works, are you ever surprised by what you hear?

BF: You have to be surprised, especially the very first time. Any time I hear a piece for the first time, I feel essentially incapacitated as far as giving any practical feedback. What you're hearing is the realization of those things that you had grappled with many months before. They're not immediate in your mind and you have to reconstruct them. What you tend to be doing at that first hearing is asking yourself if you've accomplished what you set out to do. For me at least, it's a little overwhelming.

* * * * *

BD: Is there a right way to play your music?

BF: I suspect there are several ways. I've heard different interpretations of different things. There's usually a favorite way...

BD: This is what I was driving at. Do you allow for differing interpretations in the scores you write?

BF: I try to specify what I want to hear, but sometimes it may not be as specific as I should make it. When I play a piano reduction of the orchestra score to accompany a soloist in one of my concertos, I know what the strings sound like so I can use the pedal to bring certain things out to replicate it as best as possible. I've been told my playing sounds much different from ‘practice pianists' used in other rehearsals. They are just trying to read the score, but maybe there should be more indications to help them with things like that.

BD: Should he go to the recording to get ideas, or purposely stay away from the recording so that he puts his own ideas in there first?

BF: When it's a transcription or reduction, I think it's a good idea to check the original. And since it is a transcription, you would then have the liberty to make corrections or embellishments.

BD: What about the soloist rather than the accompanist?

BF: Then it's up to the player. I know people who do it both ways, so it's a personal choice.

BD: I assume you don't want a performance to be a duplicate of any previous performance.

BF: I haven't had to worry about that. It's always nice to come back to an old friend and hear it again. If it's a replication of a good performance, then it means that whatever was in the score suggested the way to play it. I tend not to overload the music with lots of performing instructions. It's probably presumptuous to think that the music can speak for itself because anyone else obviously approaches it from their point of view. On the other hand, I'm reluctant to put a lot of directions on it because it's just excess. Many times, people don't read those things anyway. But there are time when I've very carefully notated pedaling because I want to get a specific sound, and then encountered people who change that so they're not really doing what I intended because I really put that in there for a purpose. There, interpretation is essentially a re-composition, perhaps.

BD: Let me ask the big philosophical question: What is the purpose of music?

BF: For me it's a spiritual process. Something is being released and realized that does exist on its own and apart from me, yet it's something that I had a lot to do with. But someone else must have had a lot to do with it also, because there are times when I've looked at a piece and asked myself how I ever could have come up with that. There must have been some help. I think its purpose is that it enriches our lives in any number of ways, depending on what the music is and how we choose to use it, and how involved we intend to get with it. I don't think we should use it to drown our sorrows in, but it can certainly fine-tune our sensitivities and be an important emotional tool in our lives.

BD: OK, how much in music is emotional and how much in intellectual?

BF: I think that depends on the piece you're listening to. Rachmaninoff is supposed to be all heart-on-the-sleeve, but I love to play it and I love those big juicy harmonies. There's an enormous intellect behind it as well as some very fancy fingers. I can associate with that music very well. Yes, it is very emotional. There are lots of pieces that get me down the back of my spine. The end of the Mahler Second Symphony, for instance. There are any number of other places in other pieces that may be much more subtle. One that comes to mind is Stravinsky's Orpheus which a student was recently working on. The beginning is just strings and harp playing a scale, but it sets such a marvelous scene of suspense and mystery. Others may say it's OK music, but we all react to these things differently.

BD: Does your own music make you react that way?

BF: There are spots in it where I remember my blood pressure going up while I wrote it. There can be a complex of counterpoint and certain instrumentation that is supposed to be the climax of a section, and when it happens and it's played right and the calculations are all there, WOW! It wasn't composed to produce that bit of self-pleasure, but it's pleasurable to experience it, and it's something that I experience with many other pieces, too.

BD: Do you feel you're part of a lineage of composers?

BF: Oh very definitely, yes. I've never struck out to be a single soul in the desert doing whatever it is. I think that the whole idea was put in my mind by one of my teachers. I studied composition rather late, and I did a lot of things on my own beforehand. I would see a score and imitate it in some way. I was always intrigued by the piano sonatas of Vincent Persichetti, and I never met him until many years later. I used to play a good number of them, so when I set out to write a piano piece that was in a modern style, that's what I started to emulate. That rhythmic sense, that sense of harmony that he had, and so on. That was an imitative phase, which any composer should go through because one learns any number of things from it. When we study harmony and counterpoint, we often question the reason, but when we know something about and can develop the skills, then we can apply them to something we don't know so much about. When I went to Yale, I studied with Mel Powell, who studied with Hindemith, who had this great sense of tradition. I'd bring in a few measures and say it was to be a string quartet. Powell would ask incredulously how it could stand up to all the masterworks of the literature, and someone else might not take that as a challenge. For me, I knew that my work should stand up to the established repertoire and be able to be counted. If it doesn't make it, OK. I've written only one quartet, but I realize now that I probably put enough in it for several string quartets, but I was trying to meet the challenge of the tradition and to carry on.

BD: Should you now tear it apart and use the material in several works rather than just the one?

BF: (laughing) No, I don't think so. It's fine on its own, but I realize that I had quite a few things in there that might have been extended a little longer and would not need to have been so abruptly handled. But that is essentially part of the piece, also.

BD: Is there any obligation on the part of the composer to make any piece (or each piece) a masterwork?

BF: Absolutely none. Chances are it won't be. You know that there is some sort of succession before you and that you're at least trying to fit in - not to accommodate yourself, but to be part of a historical progression. At least that's what I'm doing.

BD: I asked if you were part of a lineage of composers. Are you part of a current community of composers?

BF:

I wonder. I suppose so, although I don't know what that community

is. When my wife listens to my music, she says she hears a

passage

and it reminds her of such-and-such other piece of mine. There

are

certain elements that are common to what I use and I sometimes wonder

where

they came from. I know they're very American, also. I'm not

a person who is very acquainted with popular music. I played a

lot

of it when I played in dance bands and could improvise and do various

things,

and there's a certain harmonic component to it that gets in your

ear.

You wouldn't necessarily realize it when hearing some of my music, but

I think some of that sensitivity is there. There's a certain

sense

of harmony that is indigenous to my music. It's a way I like to

voice

chords. It's a way I like to combine notes. There are a lot

of things I avoid because the don't realize that aim. There's a

certain

way I make harmony which is not traditional, and I knew if I never

wrote

twelve-tone music, I wouldn't be doing harmony the way I do now.

All that study and training works on it, too. If I'm part of a

community

of composers, it's probably that ‘academic' community. I'm not

trying

to write pieces that prove any kind of academic thesis. When I

write

a big orchestral piece, I'm interested in the audience experiencing the

music in some sort of viable way. I'm not interested in

bombarding

them with all kinds of new sounds or nasty sounds or any number of

other

things, unless there's a purpose to that within the piece. I feel

that I'm in some sort of lineage that's very definitely American and

obviously

influenced by composers like Schoenberg and Hindemith and others that

came

to this country. I'm interested in many other things that are

going

on, but it also goes back to Mahler and those composers, too.

BF:

I wonder. I suppose so, although I don't know what that community

is. When my wife listens to my music, she says she hears a

passage

and it reminds her of such-and-such other piece of mine. There

are

certain elements that are common to what I use and I sometimes wonder

where

they came from. I know they're very American, also. I'm not

a person who is very acquainted with popular music. I played a

lot

of it when I played in dance bands and could improvise and do various

things,

and there's a certain harmonic component to it that gets in your

ear.

You wouldn't necessarily realize it when hearing some of my music, but

I think some of that sensitivity is there. There's a certain

sense

of harmony that is indigenous to my music. It's a way I like to

voice

chords. It's a way I like to combine notes. There are a lot

of things I avoid because the don't realize that aim. There's a

certain

way I make harmony which is not traditional, and I knew if I never

wrote

twelve-tone music, I wouldn't be doing harmony the way I do now.

All that study and training works on it, too. If I'm part of a

community

of composers, it's probably that ‘academic' community. I'm not

trying

to write pieces that prove any kind of academic thesis. When I

write

a big orchestral piece, I'm interested in the audience experiencing the

music in some sort of viable way. I'm not interested in

bombarding

them with all kinds of new sounds or nasty sounds or any number of

other

things, unless there's a purpose to that within the piece. I feel

that I'm in some sort of lineage that's very definitely American and

obviously

influenced by composers like Schoenberg and Hindemith and others that

came

to this country. I'm interested in many other things that are

going

on, but it also goes back to Mahler and those composers, too.

BD: Does it go back to Palestrina and Schütz?

BF: I don't think so. It also doesn't have much

Stravinsky

in it, either. I have colleagues who are very Stravinskian, so I

can see that their bents are quite different from mine in that

respect.

I think I'm part of some American community that's out there plugging

away.

The purpose of the music on my part is that it's pleasurable to write

it,

and if I have a particular idea that I want to realize, the purpose of

the piece is to release that and to realize whatever those ideas are

and

not worry necessarily what other people think of it or what community

I'm

in at one point or another.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

One of the most nifty things about the internet and e-mail is the

ease and rapidity of getting back into and staying in touch with old

friends.

When I was asked by New Music Connoisseur to prepare this

interview

for immediate use, I contacted Brian and let him know about it.

Besides

being pleased that our chat would have a second life after having been

aired a couple times on WNIB, he brought me up to date on his most

recent

items. He enjoys his new situation, saying, "There's nothing like

early retirement to allow you to get some work done!" He just

finished

his second string quartet for the Pro Arte Quartet (a Koussevitsky

Foundation

commission), and has been awarded a composer-residency at the Camargo

Foundation

Center in Cassis, France for the period of Jan-May of next year.

He is also co-director of the Washington Square Contemporary Music

Society,

which is now in its 25th season in New York City. Their website

is

www.wscms.org

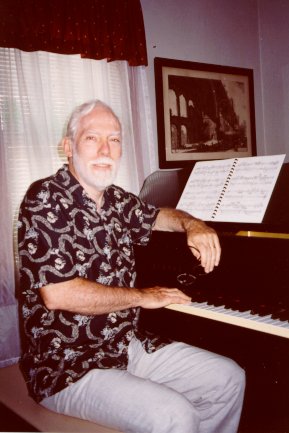

. In addition, he also responded to my request for photographs by

sending me the ones seen above. The color portrait was taken in

August

by his wife, Jacqueline, expressly for this presentation.

©Bruce Duffie

Linked from New Music

Connoisseur Magazine in September, 2001.

Sigma Alpha Iota Philanthropies, Inc., maintains concise websites on many composers. For the one on Brian Fennelly, click here .

To see a full list (with links) of Bruce Duffie's interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.