Alan Feinberg (born June 15, 1950 in New

York City) is an American classical pianist who has forged a remarkable

career based on musical exploration. His intelligence, integrity, and affinity

for an unusually wide range of repertoire place him among the few artists

who are able to build a bridge between the past and the present. He has

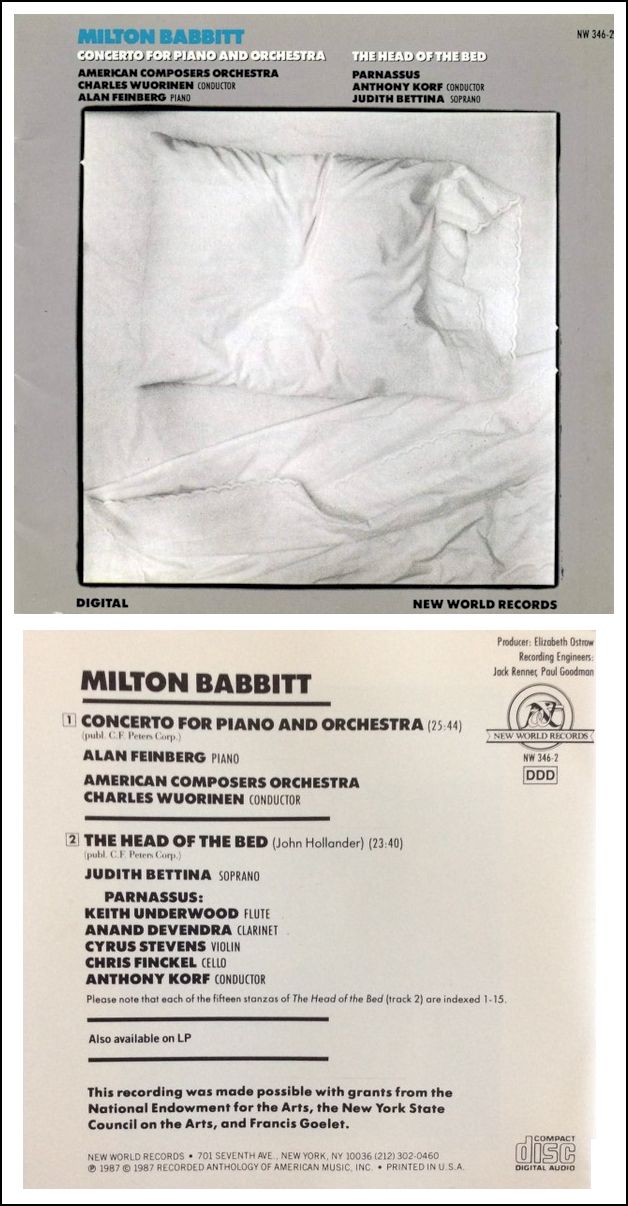

premiered over 300 works by such composers as John Adams, Milton Babbitt, John Harbison, Charles

Ives, Steve Reich, and

Charles Wuorinen,

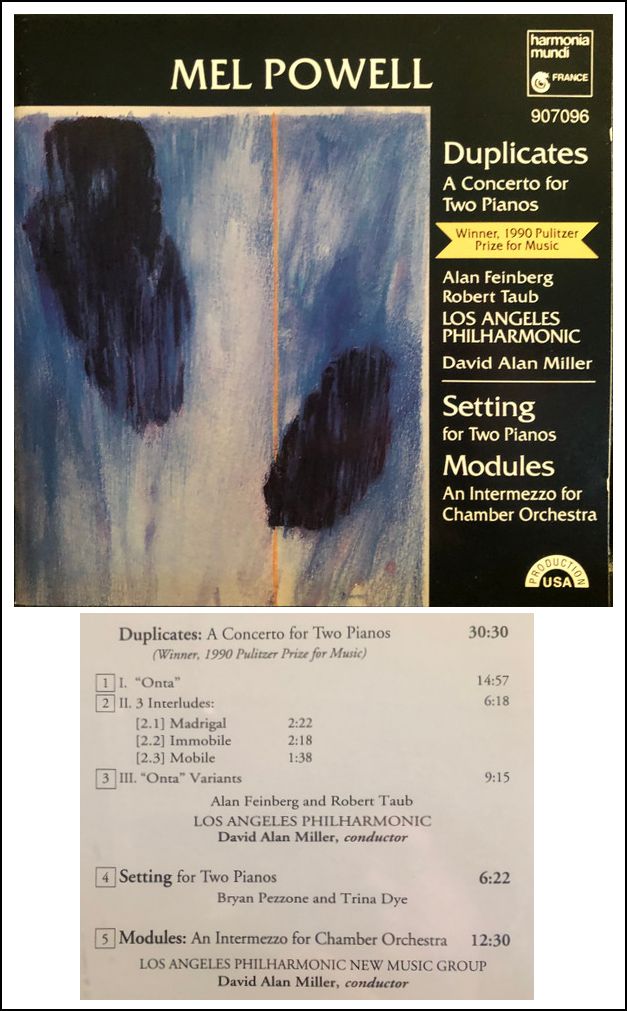

as well as the premiere of Mel Powell's Pulitzer Prize

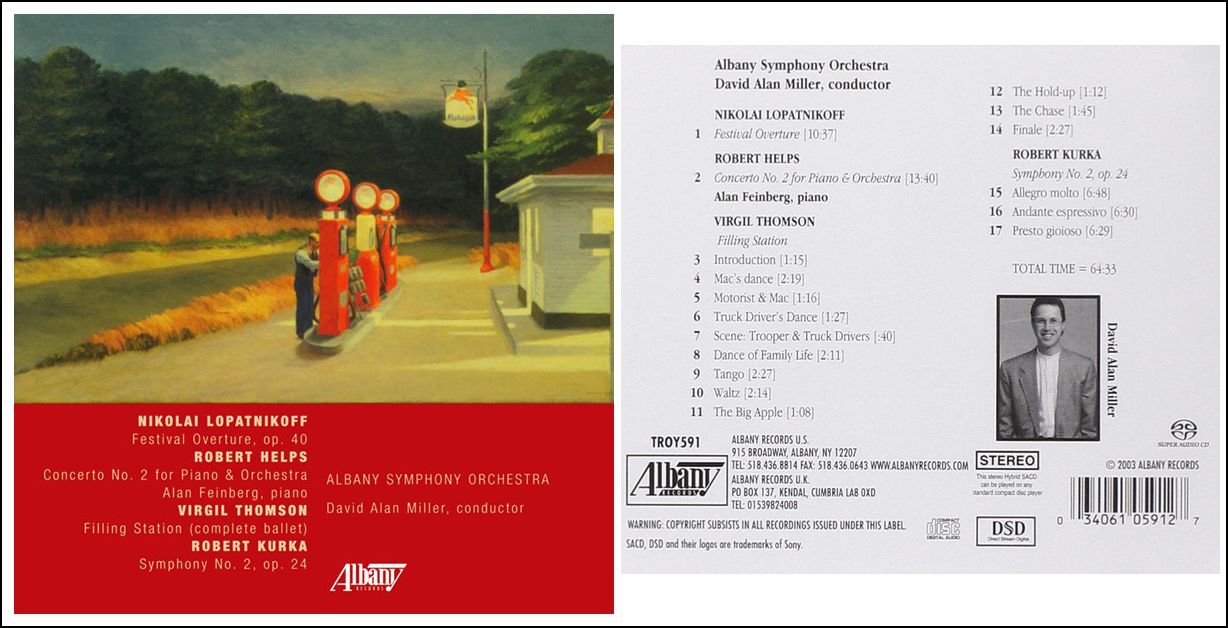

winning Duplicates [recording shown below-left]. He is an

experienced performer of both classical and contemporary music and is well

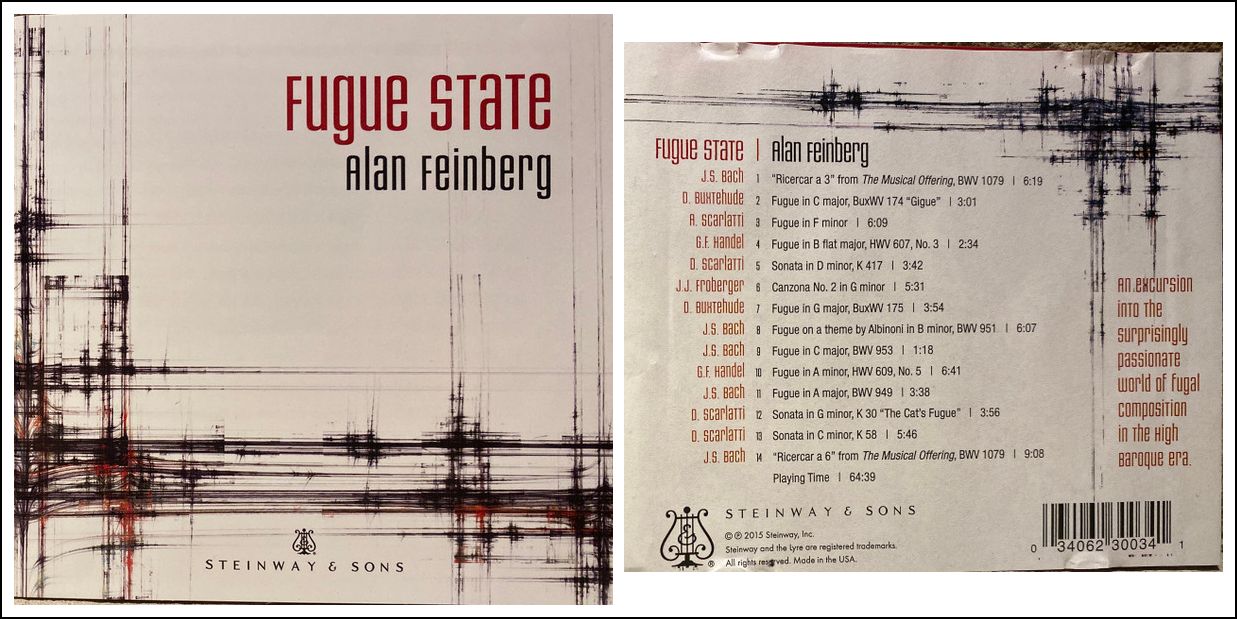

known for recitals that pair old and new music.

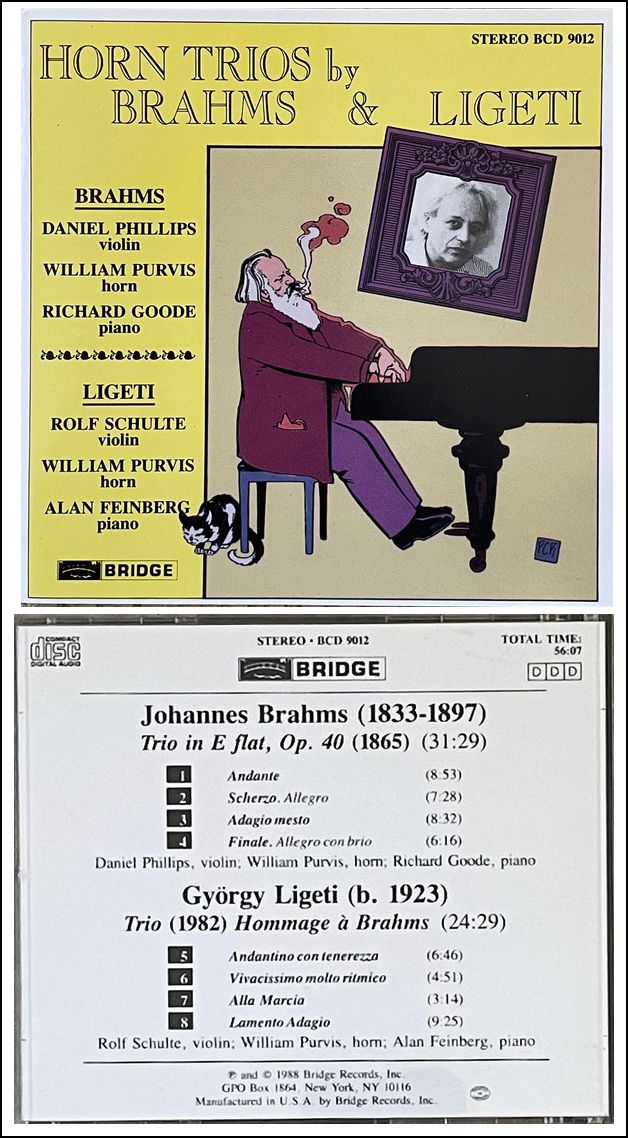

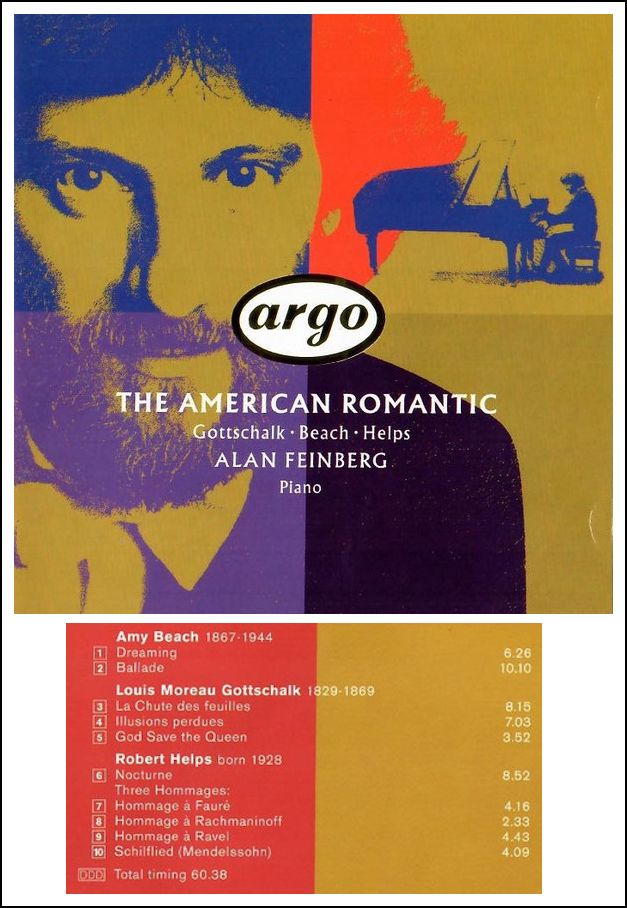

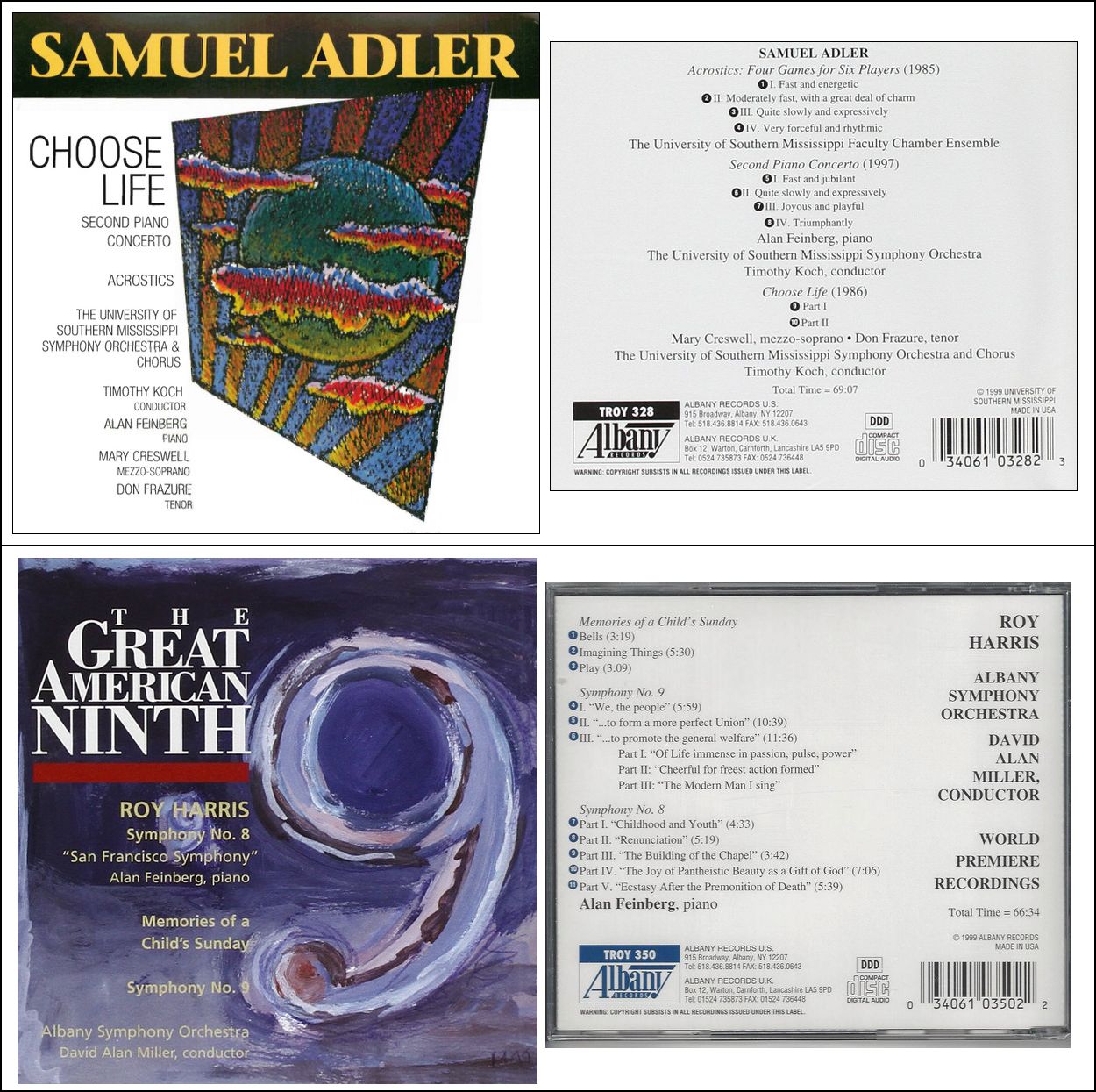

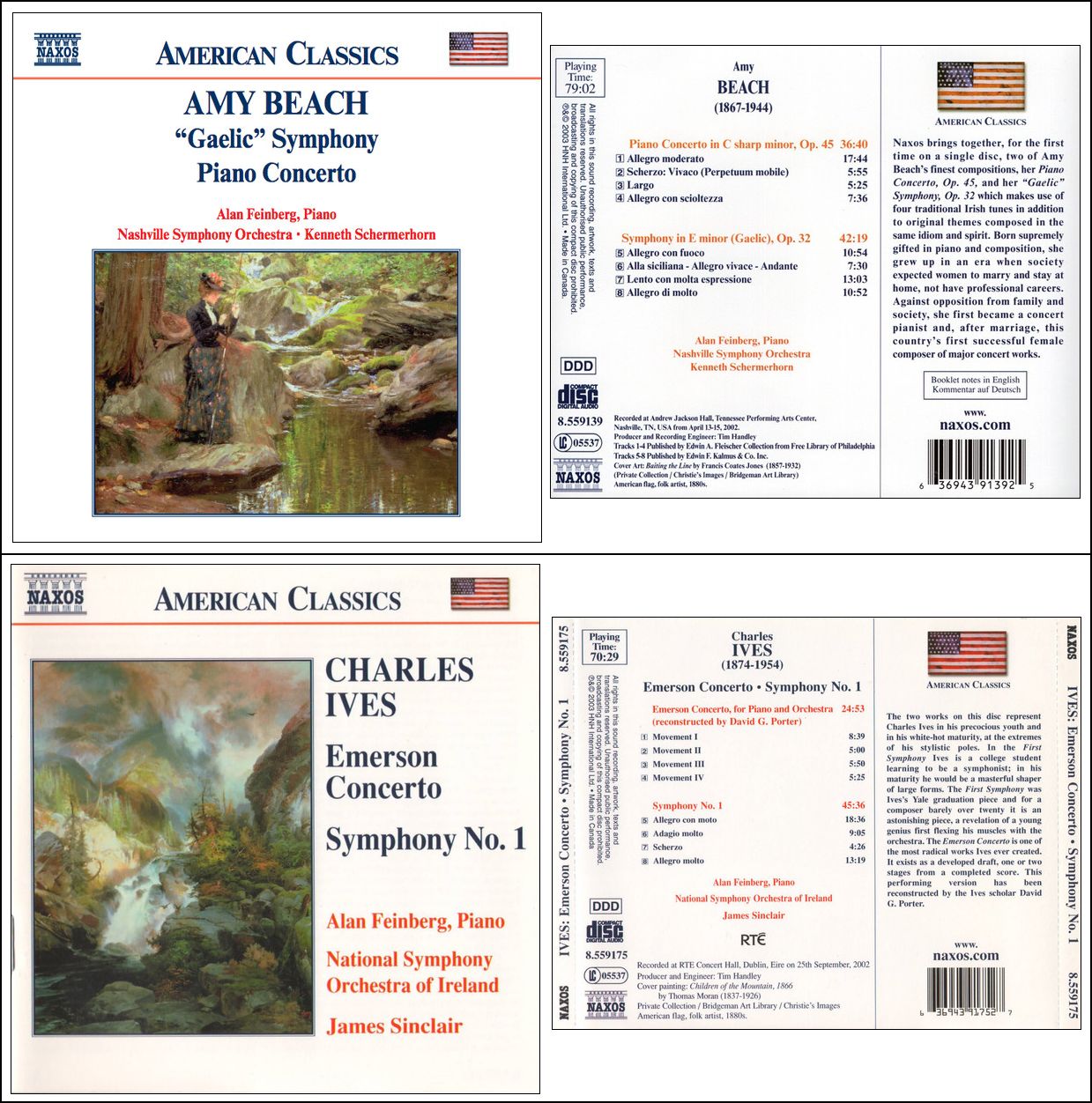

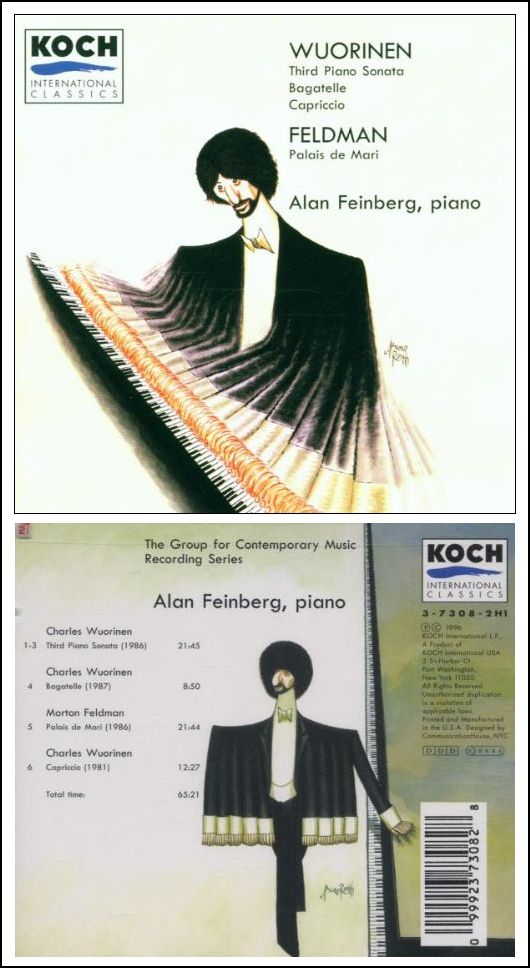

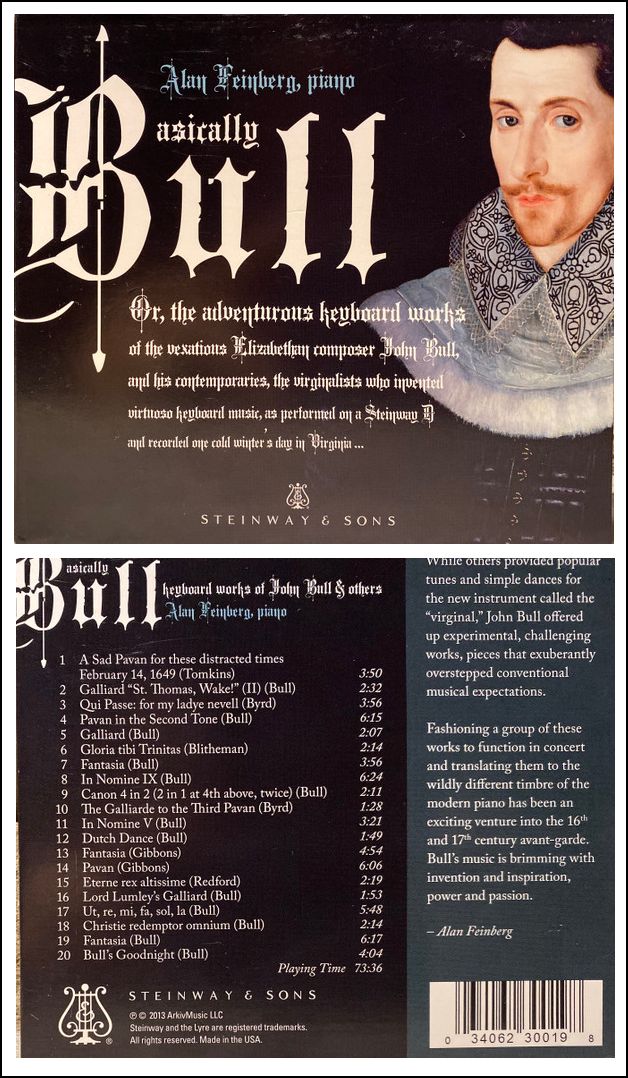

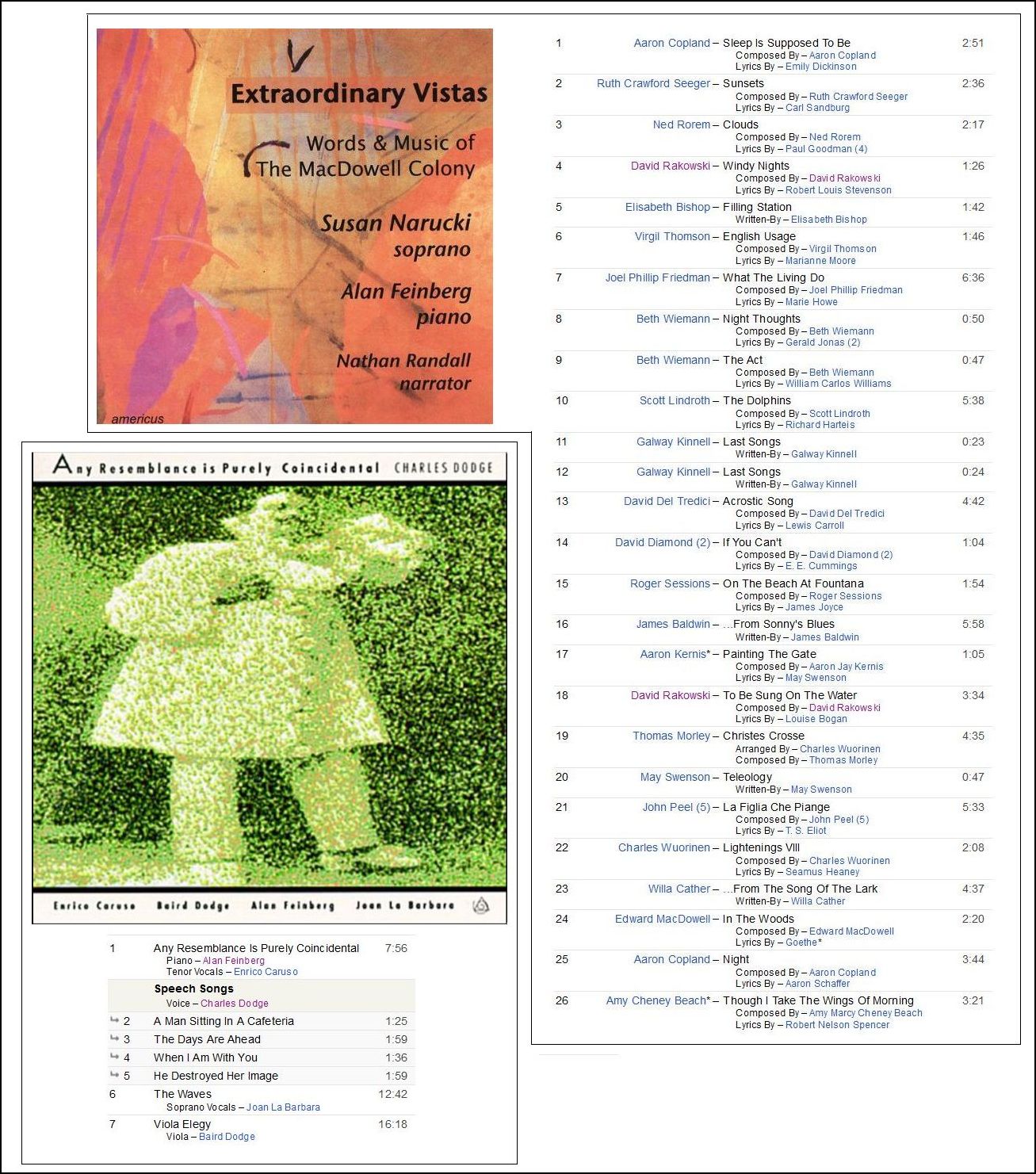

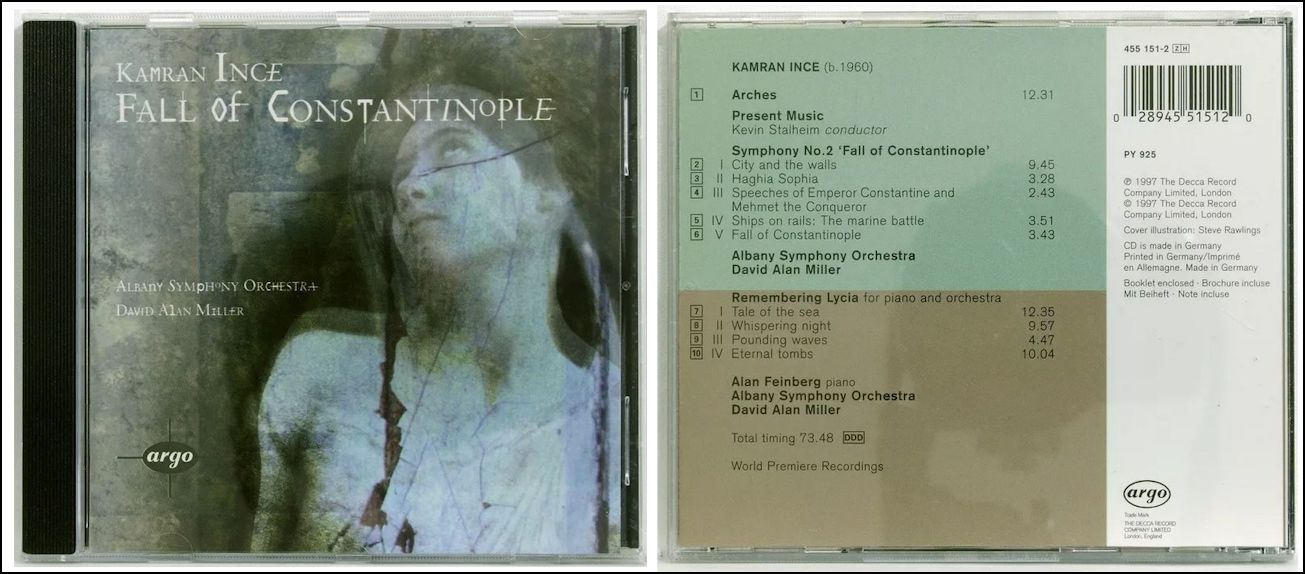

Feinberg received his Bachelor of Music in 1972 and his Master of Music in 1973 from The Juilliard School in New York City with the piano professor Mieczyslaw Munz. He began D.M.A. studies and worked with Robert Helps at the Manhattan School of Music. Feinberg toured several times with The Cleveland Orchestra and Christoph von Dohnanyi, first performing Shulamit Ran's Concert Piece (including an appearance in Carnegie Hall). He also performed the Brahms Second Piano Concerto on tour with The Cleveland Orchestra and participated in a collaboration with The Cleveland Orchestra which featured the world premiere of the recently discovered Emerson Concerto by composer Charles Ives (performed also in London, Paris, and Amsterdam), and subsequently recorded the work. Feinberg has performed as a soloist with the Chicago Symphony, The Cleveland Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, the London Philharmonia, the Montreal Symphony, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the BBC Scottish, the American Symphony Orchestra, the St. Louis Symphony, the Baltimore Symphony, the New World Symphony, and many others. Feinberg has also performed many times abroad. He has appeared as a concerto soloist at The Proms in England, with the Cleveland Orchestra in Paris, with the Amsterdam Radio Orchestra in Holland, with the Montreal Symphony, and with the various BBC orchestras. He has given recitals at Wigmore Hall in London, appeared at festivals in Edinburgh, Bath, Huddersfield, Geneva, Budapest, Berlin, Brescia, Bergamo, and Tokyo. He was also the first pianist to have been invited by the Union of Soviet Composers to represent American contemporary music, an invitation which resulted in performances in both Moscow and Leningrad. Recital programs have highlighted his interest in bridging the old and the new. These include a program of Bach and Ustvolskaya, "Reconsidering Haydn" (works of Haydn, Schubert, Weir and Kagel), "Basically Bull", a program featuring works of John Bull, William Byrd, Orlando Gibbons, Thomas Morley, and Charles Wuorinen. In recent years Mr. Feinberg has taken on work as a programmer and presenter. He has been the Artistic Advisor for the "Chautauqua Days" Festival in Castine, Maine, and Music Director of the Monadnock Music Festival. He has acted as a programming consultant for the Lincoln Center Chamber Music Society's American festival. He has put together programs of American music with himself and other American performers for the White Nights Festival in St. Petersburg and for a series of four concerts in Moscow. Feinberg has recorded four solo CDs for London/Decca that survey American music: The American Romantic, The American Virtuoso, The American Innovator, and Fascinatin' Rhythm—American Syncopation. He has received Grammy Nominations for recordings of the Babbitt "Piano Concerto" (New World Records), Morton Feldman's "Palais di Mari", and Charles Wuorinen's "Capriccio", "Bagatelle", and "Third Sonata". He has additionally recorded piano concertos by Mel Powell, Andrew Imbrie, Kamran Ince, Paul Bowles, Amy Beach, Charles Ives, Leo Ornstein, Samuel Adler, Don Gilles, and Robert Helps, as well as a Decca CD of vocal works of Charles Ives with soprano Susan Narucki and Morton Feldman's "Piano and Orchestra with Michael Tilson Thomas and the New World Symphony. He received his fourth Grammy nomination for "Best Instrumentalist with Orchestra" for his recording of the Amy Beach "Piano Concerto" with the Nashville Symphony (Naxos). Feinberg also has considerable experience as a teacher, and has taught at SUNY Buffalo, The Juilliard School, Eastman School of Music, Oberlin Conservatory, Carnegie Mellon, Duke, and Princeton Universities. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

© 1992 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 12, 1992. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1995, and again in 2000; and on WNUR in 2007, 2008, and 2018; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2010. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.