|

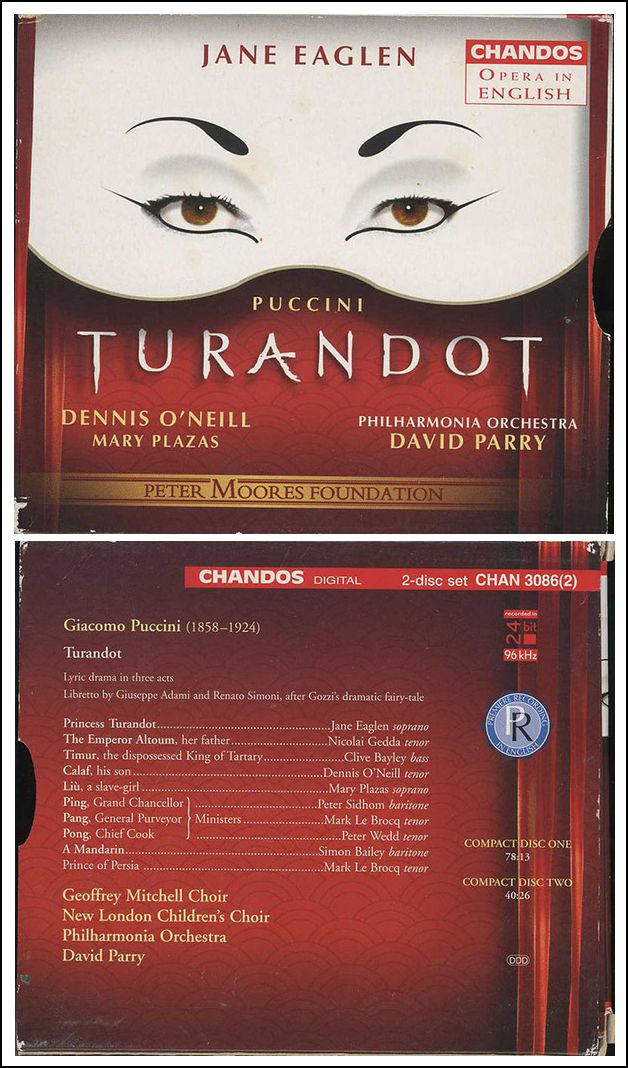

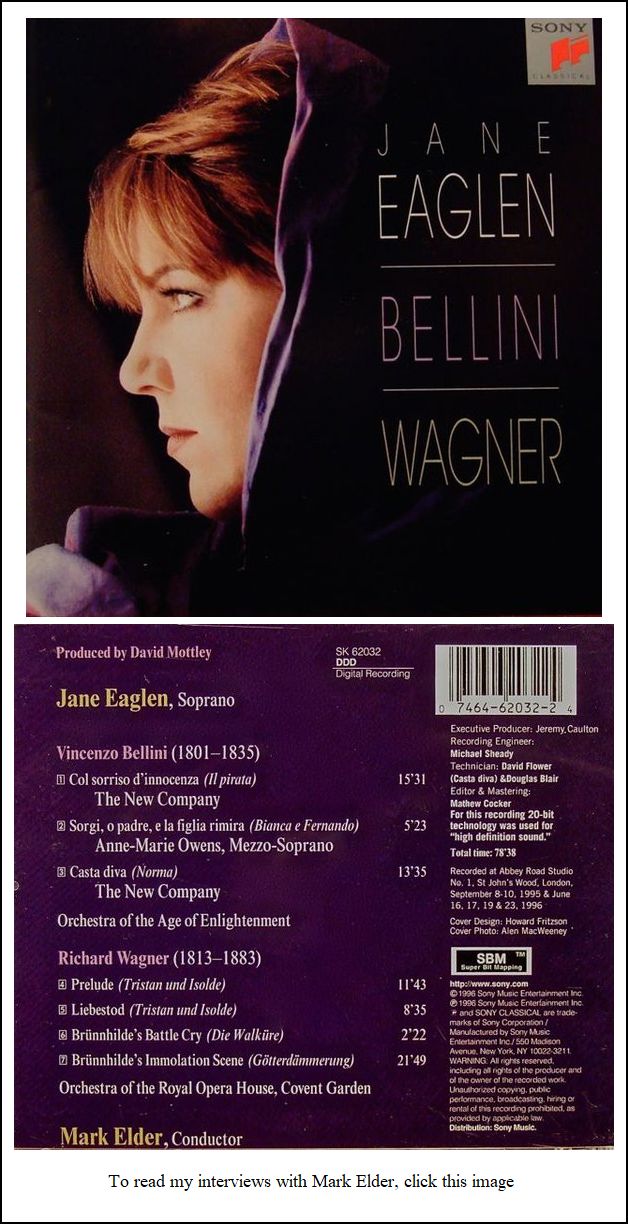

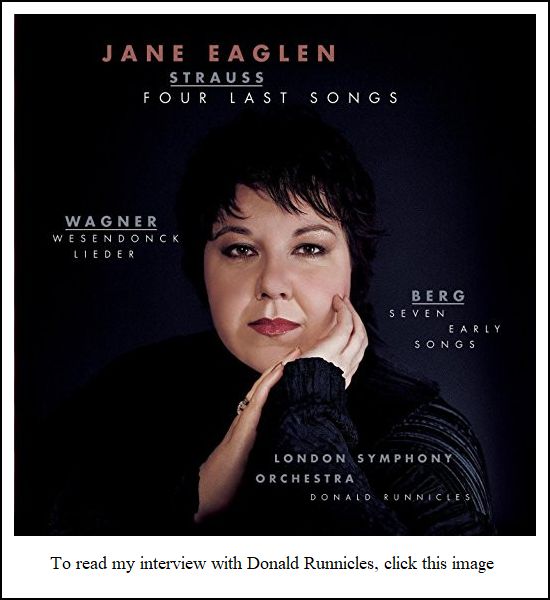

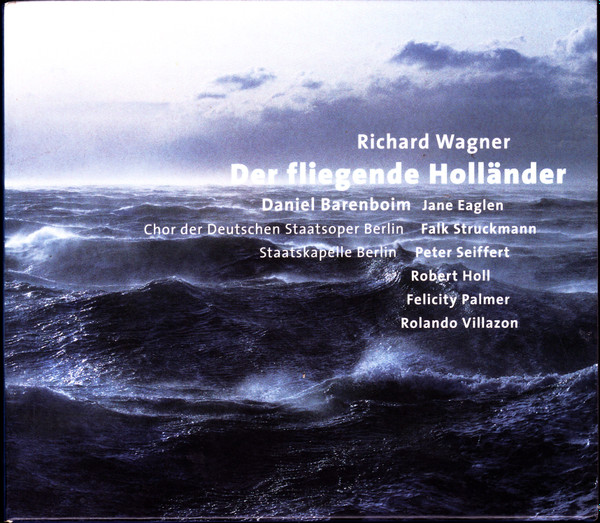

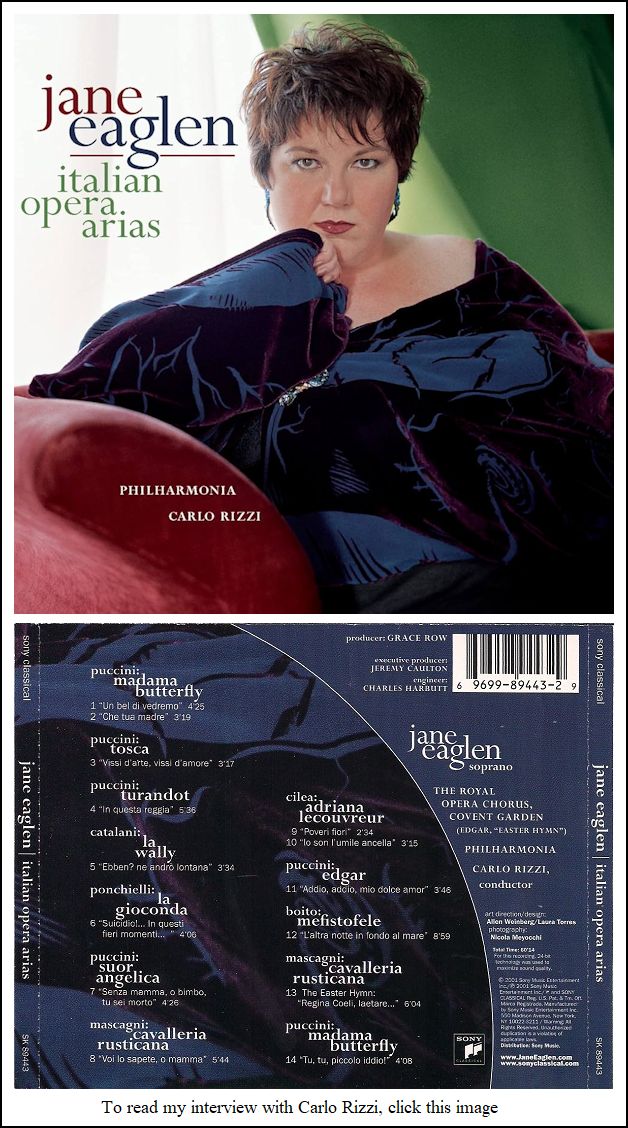

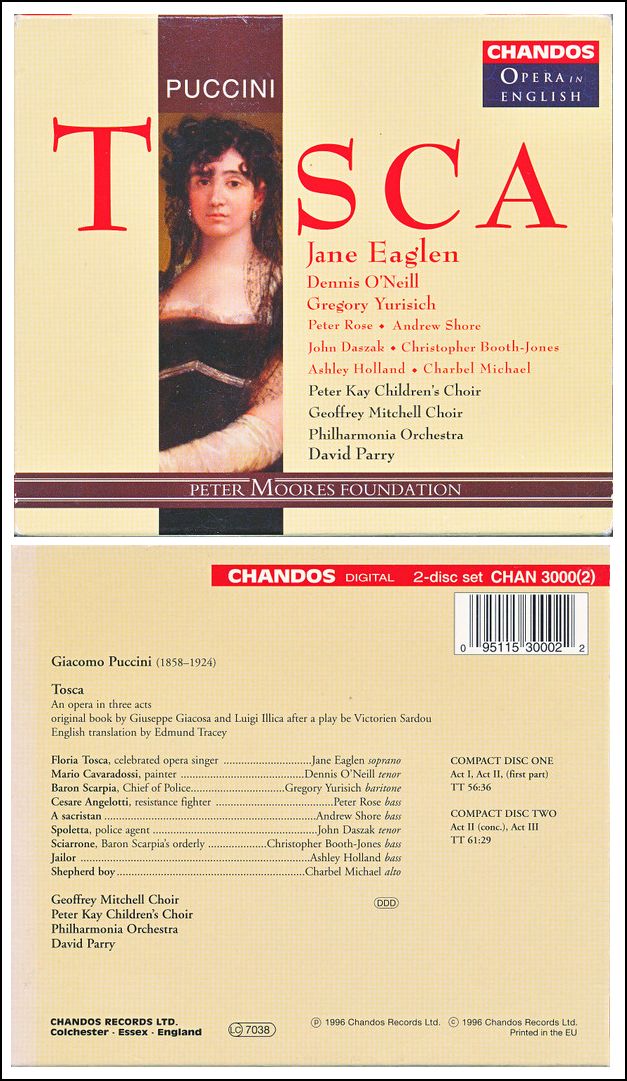

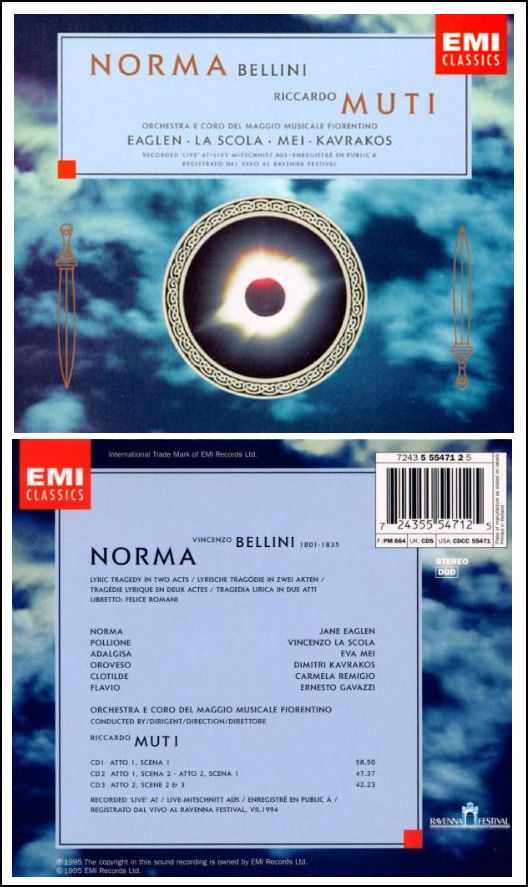

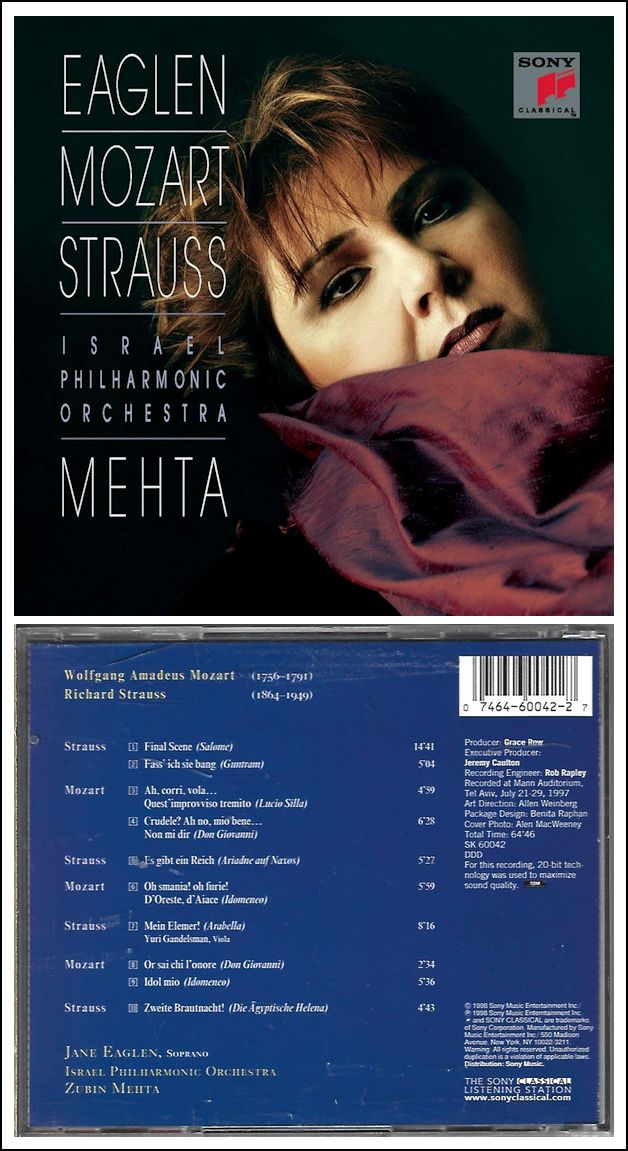

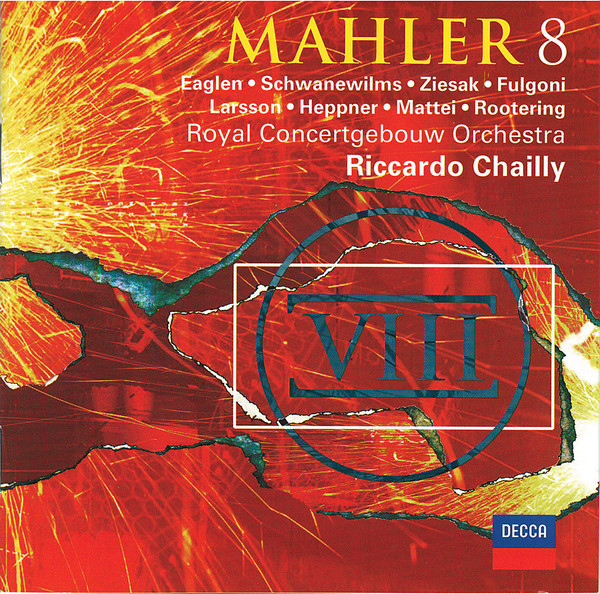

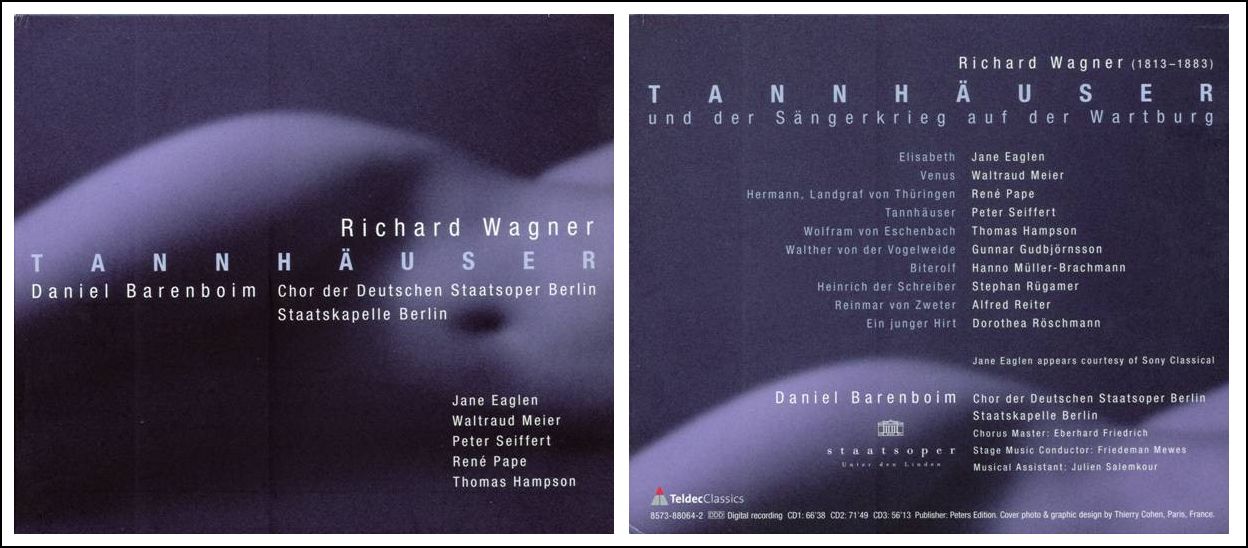

Jane Eaglen (born 4 April 1960) is an English dramatic soprano particularly known for her interpretations of the works of Richard Wagner and the title roles in Bellini's Norma and Puccini's Turandot. Her career at the Metropolitan Opera started with Brünnhilde in the Ring Cycle. She has performed at all major houses globally such as La Scala, the Metropolitan Opera House and many others. She currently resides in Boston, MA as a voice teacher at the New England Conservatory. She is the President and founder of the Boston Wagner Society. She spends her summers instructing at the Merola opera training program for emerging artists. Every year she judges several voice competitions including the Laffont-Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions. Eaglen was born in Lincoln, England, and attended South Park High School there. She started piano lessons at the age of five, continuing until she was sixteen. Her piano teacher then suggested she take singing lessons, and for a year she studied with a local teacher. After being turned down by the Guildhall School in London, Eaglen auditioned at age eighteen for Joseph Ward, the voice professor at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester. Ward recognized her potential, and took Eaglen on as a student. Within weeks Ward had directed her toward roles such as Norma and Brünnhilde. In 1984 she joined the English National Opera, and she spent a couple of years singing the First Lady in Mozart's Die Zauberflöte and Berta, the servant in Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia. Other roles included Leonora in Verdi's Il Trovatore. She was also cast as Santuzza in Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana. Eaglen broke into the major opera scene when she was cast as Donna Anna in Mozart's Don Giovanni at the Scottish Opera. She went on to sing Brünnhilde, and the title roles in Tosca and Norma with that company. She made her American debut as Norma in 1994 with the Seattle Opera as a last-minute replacement for Carol Vaness, and followed, two weeks later with Brünnhilde at Opera Pacific, a last-minute replacement for Ealynn Voss. Her first Isolde came in 1998 with the Seattle Opera, a company she has returned to consistently. She repeated the role in 1999 at the Metropolitan Opera and in 2000 in Chicago. Besides the standard repertoire, she sang Helen in the world premiere of Amelia by Daron Aric Hagen at Seattle. Her work on the concert platform includes performances of Strauss’ Four Last Songs with Daniel Barenboim with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and Gerard Schwarz with the Czech Philharmonic; Strauss' final scene of Salome with Zubin Mehta and the New York Philharmonic, and Richard Hickox and the London Symphony Orchestra; Wagner's Immolation Scene with both Bernard Haitink and Jeffrey Tate and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and Zubin Mehta and the NY Phil; Verdi's Requiem with Daniele Gatti and the Orchestra of St. Cecilia, Rome; Mahler's Eighth Symphony with Klaus Tennstedt; Nabucco with Riccardo Muti for the Ravenna Festival; Gurrelieder with Claudio Abbado for the Salzburg and Edinburgh Festivals; Die Walküre and Siegfried with James Conlon in Cologne; and many others. Her recording of Wagner's Tannhäuser with Daniel Barenboim for Teldec earned a Grammy for 'Best Complete Opera'. Eaglen was named an honorary Doctor of Musical Arts in 2005 by McGill University, Montreal. Formerly a member of the voice faculty at Baldwin-Wallace College and the artistic faculty of the Seattle Opera Young Artists Program, she frequently teaches master classes. In July 2009, Eaglen received an honorary doctorate from Bishop Grosseteste University College Lincoln. She became a Doctor of the University College. In 2010, Eaglen was named International Fellow in Voice at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama (RSAMD) in Glasgow, where she will give master classes and recitals. She is a Fellow of the Royal Northern College of Music. == Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

See my interview with Thomas Hampson

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Eaglen's apartment in Chicago on January 26, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two days later, and again that fall, and in 1998 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.