|

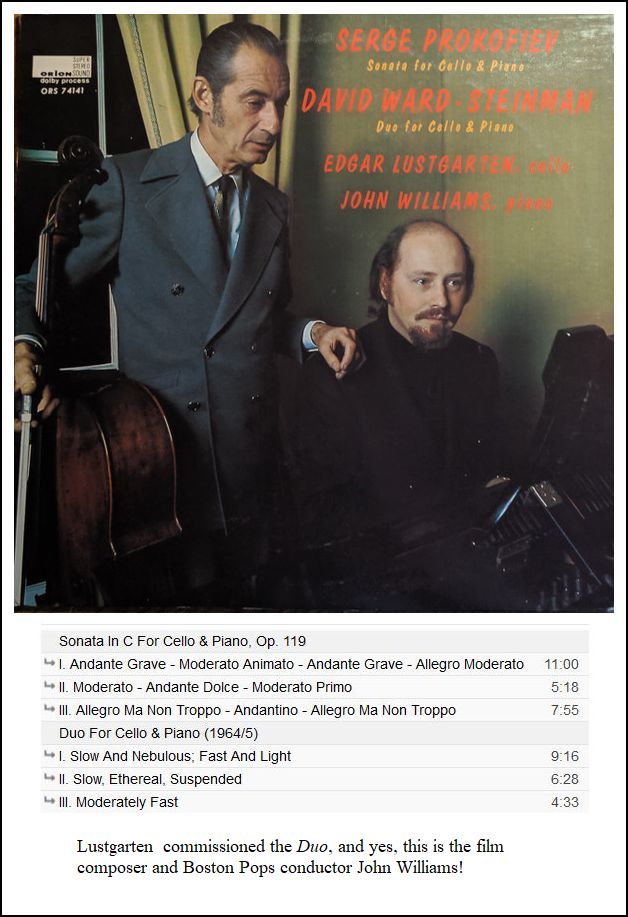

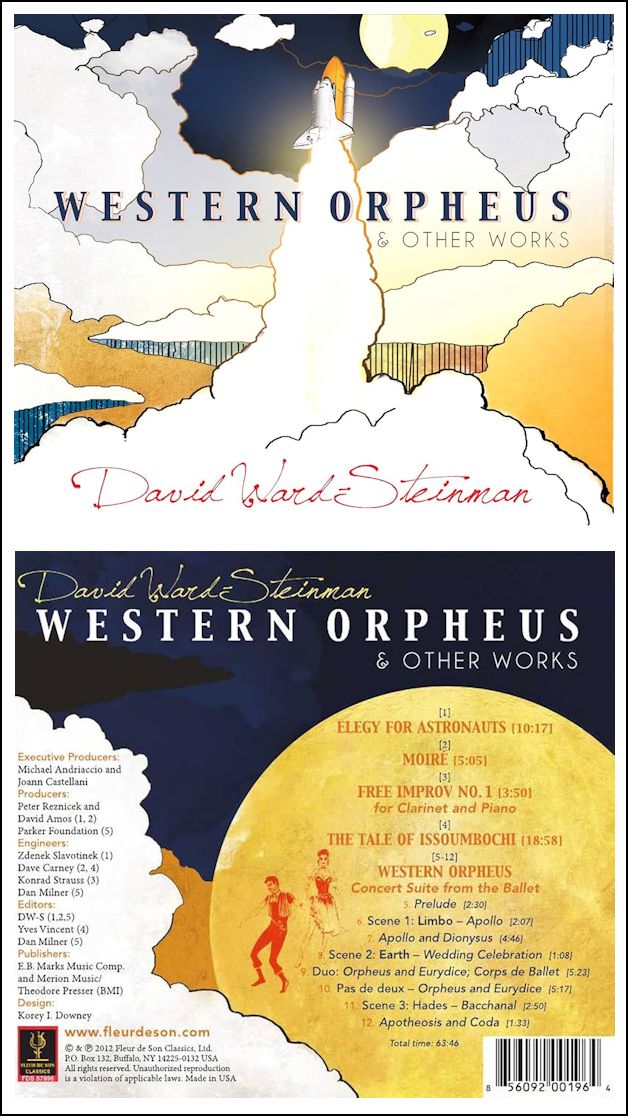

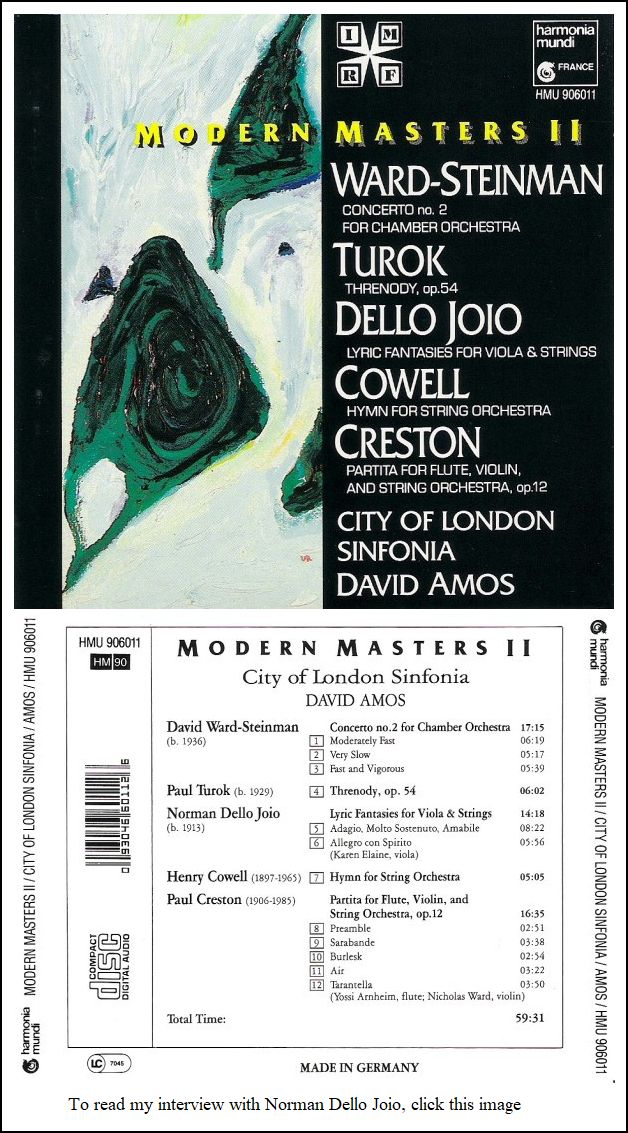

David Ward-Steinman (November 6, 1936 – April 14, 2015) was an American composer and professor. He was the author of Toward a Comparative Structural Theory of the Arts, and co-authored Comparative Anthology of Musical Forms. Ward-Steinman studied at Florida State University and the University of Illinois, where he received the Kinley Memorial Fellowship for foreign study. After receiving his doctorate, he was a fellow at Princeton University from 1970. His teachers included John Boda, Burrill Phillips, Darius Milhaud (at Aspen, Colorado), Milton Babbitt (at Tanglewood) and Nadia Boulanger. He studied piano under Edward Kilenyi, and in 1995 attended a course at IRCAM. He was Composer-in-Residence and Professor of Music at San Diego State, becoming Distinguished Professor of Music Emeritus there, and he was also an adjunct Professor of Music at Indiana University. From 1970 to 1972, Ward-Steinman was the Ford Foundation composer-in-residence for the Tampa Bay area of Florida and he spent 1989–90 in Australia under a Fulbright Senior Scholar Award, with residencies at the Victorian Centre for the Arts and La Trobe University in Melbourne. Ward-Steinman received number of commissions, most notably from

the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 12, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that year, and again in 1991 and 1996; and on WNUR in 2007, and 2014. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.