|

Peter Dvorský (born 25 September 1951 in Horná Ves, then Czechoslovakia, now Slovakia.) is a Slovak operatic tenor. Possessing a lyrical voice with a soft, elastic tone, and warm and melodious timbre, Dvorský's repertoire concentrates on roles from the Italian and Slavic repertories. Dvorský has four brothers, three of whom are also successful opera singers: Jaroslav Dvorský, Miroslav Dvorský and Pavol Dvorský. His other brother, Vendelín Dvorský, is an economist. Peter Dvorský studied under Ida Černecká at the Bratislava State Conservatory. There he also enjoyed his first successes at the Slovak National Theatre, making his professional opera debut there in 1972 as Lensky in Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin. He won the national singing contest named after Mikuláš Schneider-Trnavský at Trnava in 1973, and in 1974 he won the first prize at the international Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow. In 1975, he won first place in the singing contest at the Geneva International Music Competition which led to a yearlong apprenticeship under Renata Carosia and Giuseppe Lugga at La Scala in Milan. In the following years, he quickly achieved international fame. He debuted at the Vienna State Opera, where he was particularly successful and popular, in 1976, at the New York Metropolitan Opera in 1977, and one year later at La Scala, Milan. In these years he became one of the leading tenors worldwide. He received several distinctions, among others being a national artist and state prize-winner of the former Czechoslovakia. Since 2006, Dvorský has been the head of the opera house in Košice, then of the opera house of the Slovak National theater (SND) in Bratislava. |

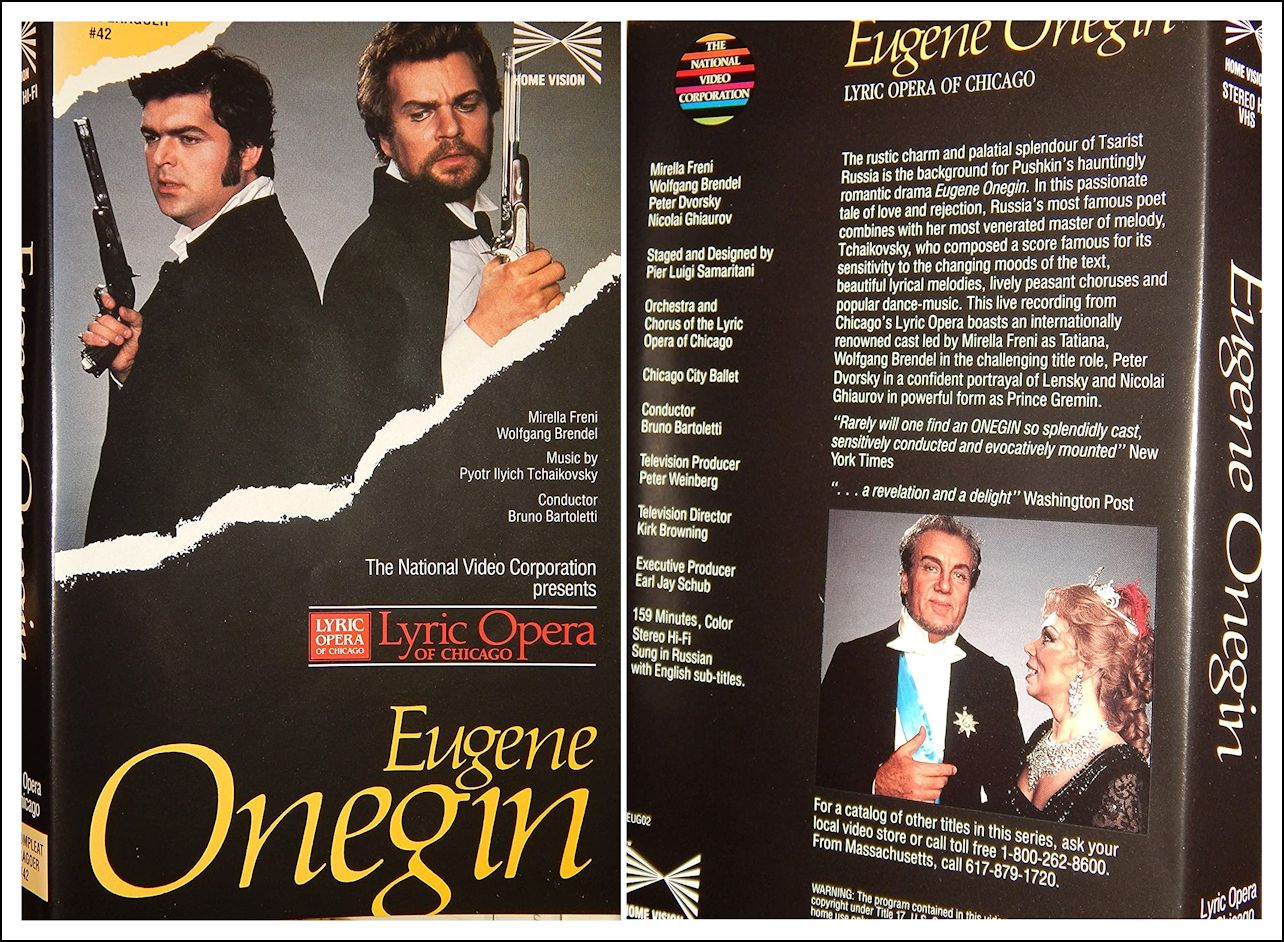

Peter Dvorský first appeared with Lyric Opera

of Chicago as Lensky in Eugene Onegin which opened the 1984 fall season.

Also in the cast were Wolfgang Brendel, Mirella Freni and Nicolai Ghiaurov,

Sandra Walker,

and Jean Kraft.

The opera was conducted by Bruno Bartoletti,

in the production designed and directed by Pier Luigi Samaritani,

lit by Duane Schuler,

and the ballet directed by Maria Tallchief. [Video

cover of that production is shown at the bottom of this webpage.] During

that run, he was gracious to spend a few minutes with me discussing his

various roles, and other musical topics.

Peter Dvorský first appeared with Lyric Opera

of Chicago as Lensky in Eugene Onegin which opened the 1984 fall season.

Also in the cast were Wolfgang Brendel, Mirella Freni and Nicolai Ghiaurov,

Sandra Walker,

and Jean Kraft.

The opera was conducted by Bruno Bartoletti,

in the production designed and directed by Pier Luigi Samaritani,

lit by Duane Schuler,

and the ballet directed by Maria Tallchief. [Video

cover of that production is shown at the bottom of this webpage.] During

that run, he was gracious to spend a few minutes with me discussing his

various roles, and other musical topics. BD: [With a gentle nudge] Do you promote yourself

in the last act?

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Do you promote yourself

in the last act?|

Suchoň's original conception was to write the opera using two different styles - a quasi-impressionist style to accompany the thoughts of the characters, and a more realistic, nationalist style to accompany external events. Traces of this dualism remain in the score, although Suchoň realized his original ideas were impractical. Although the premiere was successful, the governing Slovak Communist

Party insisted that the original ending be changed to make it more 'optimistic'.

Other serious changes were forced on the composer, involving dismantling

the very important 'framework' to the opera which posited the story as

the result of a wager between the Poet and his Double (spoken roles),

and, inevitably, the toning down of any references to Christianity. At

first Suchoň refused to make any alterations; the opera was withdrawn

from the repertoire. Pressure from his musical colleagues, who realized

the importance of the work, induced him to change his mind, and this

'revised version' was performed in Czechoslovakia and abroad in the 1950s,

the original ending only being restored in 1963. Complete reconstruction

of the original, including the participation of the Poet and his Double,

had to await the composer's centenary in 2008, when Suchoň's work as originally

conceived was performed in Banska Bystrica.

|

The reason why the Czech composers are not so well-known

is that there are not so many as there were in Italy or France at the time.

Although the three major ones are fairly well-recognized in the West

now, many operas are fairly often represented around there. But managers

from the West never go to see what happens in Czechoslovakia, and this

might be a reason why things are not exported so much. Czech artists

are now very much in demand, and they could do something with the Czechoslovakian

composers. Then those operas could enter the repertory because they’re

beautiful. One by Ján Cikker (1911-1989), which is called

Hra o láske a smrti [Play of Love and Death, after

Romain Rolland], is a beautiful, beautiful opera, but there’s only a small

tenor role. It’s very difficult to put on, so nobody sees it, nobody

hears it, and nobody knows it, but it’s a wonderful, wonderful work.

People tend to think that nothing important musically really happens there,

which is not true, of course. Also, there are singers that are just

wonderful in Czechoslovakia who are not coming very much to the rest of

Europe.

The reason why the Czech composers are not so well-known

is that there are not so many as there were in Italy or France at the time.

Although the three major ones are fairly well-recognized in the West

now, many operas are fairly often represented around there. But managers

from the West never go to see what happens in Czechoslovakia, and this

might be a reason why things are not exported so much. Czech artists

are now very much in demand, and they could do something with the Czechoslovakian

composers. Then those operas could enter the repertory because they’re

beautiful. One by Ján Cikker (1911-1989), which is called

Hra o láske a smrti [Play of Love and Death, after

Romain Rolland], is a beautiful, beautiful opera, but there’s only a small

tenor role. It’s very difficult to put on, so nobody sees it, nobody

hears it, and nobody knows it, but it’s a wonderful, wonderful work.

People tend to think that nothing important musically really happens there,

which is not true, of course. Also, there are singers that are just

wonderful in Czechoslovakia who are not coming very much to the rest of

Europe. BD: Do you enjoy singing?

BD: Do you enjoy singing?

© 1984 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 14, 1984. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1996. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.