Conductor Antal Doráti

A Conversation With Bruce Duffie

Conductor Antal Doráti

A Conversation With Bruce Duffie

Conductor, composer, teacher, author. All of these describe Antal Doráti (1906-1988). A superb musician who traveled the world, he led many fine orchestras and touched innumerable lives both in performance and on recordings. Specific details of these and other accomplishments can be found in the biography at the end of this interview.

It was in anticipation of his 80th birthday that I contacted him and arranged a phone chat. He called it "that awful birthday" and was glad it only happens once. “It is not me who celebrates," he went on, "but my friends. It is always very nice, so one accepts it with pleasure and gratitude." In my opinion, it is we, the public, who have the pleasure (of his music) and should express the gratitude for the work and influence he has had for so many years and over so much repertoire.

Because of the enormous amount of recordings he made, it was natural that

WNIB should be able to present a comprehensive picture of the artistry of

Antal Doráti. We played symphonies and other orchestral music,

ballets, suites and operas, as well as programs of his own original compositions.

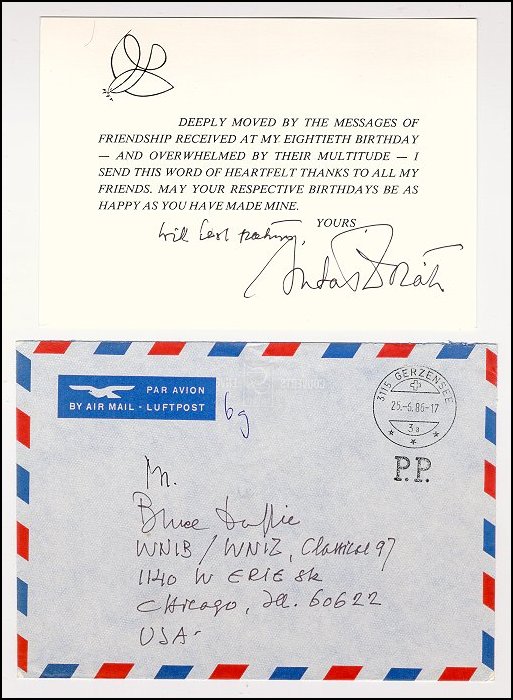

This interview was transcribed and portions were included in an essay that

appeared at the beginning of the monthly WNIB Program Guide.

I also ran some of the audio during the special programs which were aired

throughout the month. Soon thereafter, I received the card which is

shown at right . . . . .

Because of the enormous amount of recordings he made, it was natural that

WNIB should be able to present a comprehensive picture of the artistry of

Antal Doráti. We played symphonies and other orchestral music,

ballets, suites and operas, as well as programs of his own original compositions.

This interview was transcribed and portions were included in an essay that

appeared at the beginning of the monthly WNIB Program Guide.

I also ran some of the audio during the special programs which were aired

throughout the month. Soon thereafter, I received the card which is

shown at right . . . . .

Now, in 2007, I am happy to be able to give new life to this conversation

by posting it, in its entirety, on the internet.

Bruce Duffie: Is conducting something that can be taught, or must it be learned on one's own?

Antal Doráti: This is a big problem. I always say that conducting cannot be taught. However, experience can be shared. In the realm of the arts, practically nothing can be taught. If one knows a lot, one can learn more. The essential ability cannot be given. What makes the fine artist is the talent plus experience. And experience has to be gathered personally - you cannot have it from somewhere else. You cannot get experience-pills, or experience-injections. You have to be there and do it, be it in conducting or singing or painting or whatever. An experienced man could help - not to shorten the road to experience for a younger man, but to show him the path which he can take to make the amount of his errors a little bit less. What I am against is the conducting courses and conducting diplomas. Those are not valid because there is so little to go on except the conducting itself. A performing artist can show what he can do on his instrument, and you can say that you will learn that, after which you will go out and get the experience to perform on the instrument you already know how to play. But in conducting that is not possible because there is no such thing as conducting technique.

BD: There is no instrument on which to learn?

AD: There is the orchestra, but it is not available. You've got to be there and be good enough not to be chased away, and when you stand there year after year, slowly you become a conductor while you are exercising your profession.

BD: In Europe, it seems that a young conductor can learn his craft in the smaller opera houses.

AD: In the olden days - in my youth - that was the only way.

BD: Where does one go today to become a conductor?

AD: Today it is really the same situation. You have to go somewhere. We went where we could, also. In my day, the new world didn't exist as far conducting counted. Nobody went there to learn. When you knew something, then you might be invited to America, but now there is a whole new generation which rightly aspires and demands a place to learn. I don't think the young American needs to go to Europe to learn. There should be enough place for them here.

BD: Are there enough young conductors coming along - or perhaps too many?

AD: This is hard to say. In every generation there are many aspiring ones and a few who arrive. There is nothing unnatural about there being too many at the beginning. That is a normal process.

BD: It is generally accepted that instrumental playing has become more proficient, and the technique has become more solid over the last few years. Is that same thing true with conductors?

AD: No, unfortunately not. Neither the learning nor the teaching nor the experience of the conductors has become greater than it was 50 years ago. However, the general education of people in many places of the world has become better, so the 100 players in the orchestra are better off as well as being better technically.

BD: Are they better musicians, though?

BD: Are they better musicians, though?

AD: Talent wise, no, but they are better prepared. I think there were very good musicians 50 years ago and 100 years ago as well, but today their general schooling is better. They know more geography and history and more of the world today. For instance, I feel much less lonely today in an orchestra than I felt when I was a beginner. I am amongst colleagues now and I wasn't 50 years ago. The difference between my orchestral players was much greater in 1930 than it is in 1980. And I take into account that I've gotten much better also in the meanwhile.

BD: Can conducting be a collaborative art or is it dictatorial?

AD: Well nothing in the world which is dictatorial is good. I think that every art is an art of authority, but between "authoritarian" and "dictatorial" there is a vast difference.

BD: Then let me change the question. Is conducting becoming more collaborative than authoritarian?

AD: Certainly it is becoming more collaborative because orchestral players are much better and more effective collaborators today than they were.

BD: We've been talking about orchestral work, but does the same hold true in the opera house?

AD: I think exactly, yes. The difference between the concert podium and the opera house is the different dimensions of the stage. In the opera house you have the orchestra pit and then the singing soloists, then the chorus and the technical personnel (the stage manager and the stage director as well as the designer), so there is this vast scope of different factors who must collaborate to one goal. I think definitely the collaboration today is much more intimate and more exciting and more interesting. There are also more debates about everything, though.

BD: I was wondering if the balance of power in the opera house was shifting too much toward the stage-director?

AD: This is another matter altogether. In my life it goes by periods. When I began, it was the end of the period of the singer. The singer was the king. Then that was finished and came the epoch of the conductor. It was the conductor who was the king. That is vanishing, and now comes the epoch of the stage-director who is the king. And that will vanish and we of course don't know what comes next, but I hope that the epoch of the composer will be next.

BD: Why does it seem not too many great operas being written today?

AD: We are living in a very vague and confused epoch in which it is very difficult to produce masterpieces, and it is very difficult to recognize masterpieces because of the vastness of the material at hand.

BD: Is it perhaps the public's fault for expecting every new opera to be a masterpiece?

AD: Wasn't that so all the time? I don't think that is the reason. Probably the problem is really that there is less possibility of producing new operas. Every opera house in the world is having financial problems, therefore they have to rely on successful repertoire. To make a new production is a tremendous task, and comparing that against the past, making a new production was a natural thing to do because there were not so many old ones to go with.

BD: Where is opera going today?

BD: Where is opera going today?

AD: I think exactly where every other art form is going - toward its own future, and we don't know what that is. I am very interested in that because I just completed an opera myself, so I am now in the chorus of opera composers. The new opera is called in English The Chosen, and it is a biblical theme. The chosen person is the prophet Elijah. Actually it is the life-story of Elijah, which is immensely dramatic and very exciting. It’s like a whodunit actually.

BD: Is it about to be produced?

AD: That is being negotiated in Europe. I just wrote it because I had to write it.

BD: Is that good advice for young composers - to write things that they have to write rather than waiting for commissions?

AD: Nothing should be written which doesn't have to be written, so the question is the other way around. If I have to write something anyway and by chance it is commissioned, then that is a very fortunate coincidence. But just getting a commission and not knowing what to do, one shouldn't produce a piece. Any creative artistic achievement must be the result of an inner force. Nothing else will do.

BD: You must tell it to the world?

AD: You must tell it, to whom is not important. It's like an outcry. I don't know who will hear me, and I'm not addressing it to any specific person. Even if I'm composing a commissioned piece, I'm not addressing it to the person who commissioned it. Of course I ask if they would like this piece, and they say yes, that's fine. If he says no and I have no other idea, then I just decline the commission. The Detroit Symphony just commissioned me to write something for my own 80th anniversary, and I think that is one of the most touching things that ever happened to me. It was something that I wanted to write anyhow, and then the commission came. I call it a symphonic fantasy, and I gave it a name which is the name of an essay by Erasmus of Rotterdam and is called Querela pacis. It means the complaint of peace. It's something about which we all should think nowadays, the cause of peace. The quote of my title was written in 1517, and the complaint of peace was just as acute as it is today.

BD: You've said of your own compositions that they are "recognizably contemporary but not afraid of melody."

AD: I would say that again, yes. I still believe that.

BD: Are perhaps too many contemporary composers afraid of melody?

AD: I don't know whether they are "afraid of" it. I just use the expression because I have this fancy to use it, but maybe they don't esteem it. Maybe they want to express their things in other ways. I cannot live without melody. It is my melody; it is the melody of this century, but it is a very essential part of music. The three components of life are rhythm, harmony, and melody, and music is the only art which really puts these three elements into the fore. Melody is the element of love. I cannot live without love. I don't know who else can, but I can't. Then there is the element of work and that is rhythm. That is the pulse which makes one go. The heart works in your body and in my body, too, and I work with a certain rhythm. Then comes the tremendous and very human aspect of harmony, which is community. This is the thinking of one person in connection with another, or with another or several more. Of course we can use these elements in connection with our own time, and the very great ones of us can use it in a prophetic way projecting their own force into the future if their talent is so great and their brain is so encompassing.

BD: Is that what makes the individual voices of each composer different - the balance among those three elements?

AD: Perhaps that is one. Also their strength and their direction. One is strong and another is tender.

* * * * *

BD: Let me move the conversation to some of your recordings, and specifically your operatic sets. You've recorded several of the operas by Haydn. Are those special to you?

AD: Yes, because the composer is. I think that Haydn is a composer to re-discover in our days and in our terms.

BD: Can you say why he's been languishing for so many years?

AD: Well, you cannot say he wasn't performed, but he was

performed very sparingly. Only a few of his works were done and were always

repeated. The reason for that, I think, is just human modesty. The taste

of a public is modest; they are satisfied with little. But that is why we

are here - to show them a wider horizon. And if we, as performers, can be

successful in augmenting the public of any great composer we believe in,

then we are already successful people. If, before my recordings and performances,

Haydn had X number of listeners, and after he had X+10, then I have reason

to be pleased.

AD: Well, you cannot say he wasn't performed, but he was

performed very sparingly. Only a few of his works were done and were always

repeated. The reason for that, I think, is just human modesty. The taste

of a public is modest; they are satisfied with little. But that is why we

are here - to show them a wider horizon. And if we, as performers, can be

successful in augmenting the public of any great composer we believe in,

then we are already successful people. If, before my recordings and performances,

Haydn had X number of listeners, and after he had X+10, then I have reason

to be pleased.

BD: Are you happy that the recordings have spread the music to an even wider audience than just the performances in the theater?

AD: I have no recourse to anything else.

BD: Well, should the operas of Haydn be staged today?

AD: They are, in a modest way, and increasingly - some, I'm happy to say, in the wake of my recordings. The Haydn operas are problematic because some have rather weak libretti - weak in our dramatic sense. In his own time, he was very satisfied with them. They didn't have the spark like the Da Ponte libretti did for Mozart, but even Mozart's operas with poorer libretti did not turn out as well for him. But what we think of as poor libretti, when you scratch under the surface, you find they are not really so poor. For instance, they say that Il Trovatore has a poor libretto, but I would not agree. I think that has a splendid libretto. It's outlandish, it's over-romantic, but look at the characters which are shown on the stage and their extreme passions which are shown. You see?

BD: Then it's our responsibility as public or performers to find the good in any libretto?

AD: If there is good, yes, you should find it.

BD: Are there any works which attain popularity or notoriety which are genuinely poor?

AD: For a short period of time, yes. One can find them, but for a long period, no. They always disappear and then never come back. A good work can certainly be in vogue and then disappear, but it certainly will come back at one time or other.

BD: So this is what you've done with the Haydn operas?

AD: I don't know yet. That is for the future to decide. I brought them back, but whether they will stay I don't know. If they don't stay because of my recordings, I am certain that in another 20 years there will be other recordings or performances and then they will stay.

BD: You've recorded so much of Haydn - the operas, concerti, symphonies, minuets, etc. Is there a cohesiveness about his works?

AD: That is a very fine question. I will say yes, and this one of the rare occasions where you can watch the long life of a creative talent which grew during the years. One could say that Haydn began as a talent and ended up as a genius.

BD: Asking just about the operas, you've recorded

eight. Are there any which are your favorites?

See my Interviews with Norma Burrowes, Robin Leggate, Anthony Rolfe Johnson,

Lucia Valentini Terrani,

Ileana Cotrubas,

Arleen Auger, Elly Ameling, George Shirley, Benjamin Luxon, Helen Donath, and Kari Lövaas.

AD: Well, in a way all eight are my favorites. There is a ninth which I've not done yet - Orfeo. There are 6 more operas extent from Haydn, but they are either not complete or they are very small. There are two puppet works and three small operas.

BD: Did you have any problem teaching the Haydn style to contemporary singers?

AD: No, none. They came from very different stables and they did wonderfully. They formed a tremendous unity for these operas.

BD: I'm glad you're happy with the result.

AD: I am indeed. It took seven years. I did other things also during that time, but I made them over seven seasons.

BD: Let me turn to another of your recordings, Bluebeard's Castle. How do you see the work?

AD: I've done it in the theater, in concert, and on the stage. I cannot say how it works as a record. I can only say whether it is a good performance or not. I am not there when it is listened to; I cannot watch the reaction. To read in the newspaper or get the check for which I see how many copies are sold, that doesn't tell me much about the effect of the piece. For instance, I have absolutely no proof that all those people who bought the record really listened to it! In concert and onstage, both can be very effective, but it depends very much on the singers. Of course the orchestra has to be good because it's a great orchestral piece. And then there is the problem of the language. So far, I have not encountered any translation which would give a satisfactory impression on the listener. I would go so far as to say that it is perhaps better to perform it in Hungarian for a public which does not speak Hungarian, than in their own language. There is a spoken prologue, and I have always had that spoken in the language of the audience.

BD: Have you had any experience with this new technique of "supertitles" in the theater?

AD: No, I've never seen them and never worked with them.

BD: I was wondering if this would be the ideal compromise between having opera in the original and yet having the language barrier broken.

AD: Not having seen this, I shudder about it. It is very similar to having subtitles in a movie. That I have seen and that always distracted me. I would first try very hard to have the singers pronounce the text well. In every country where there is a real indigenous opera culture, or let's say a theatrical culture, the opera, in the main, will be performed in the vernacular. The opera in the original language is a special treat. That's the ice cream after a good dinner.

BD: Since Bluebeard is such a short work - running only about an hour - what kinds of works go best with it on the other half of the bill?

AD: I've done other Bartók, The Miraculous Mandarin as a pantomime, or one can do another short opera.

BD: I just wondered if, perhaps, a full evening

of Bartók was too much.

AD: No. If the performances are good, that is very good and very good in style. I've tried several things including performing an orchestral piece. That worked rather well. I've tried other operas such as a baroque opera before it, but I've never tried Cavalleria Rusticana. That would be too obvious. I did once Oedipus Rex by Stravinsky, and that with the Bluebeard was a very intriguing combination. Both are very sad, so it was a very dark evening, but a very powerful one. I also once did Gianni Schicchi. Perhaps the best is to have all Bartók.

BD: What about Il Prigionero of Dallapiccola? Is this really a good work?

AD: Oh, I love it. I made a record of it

just to show how strong a work it is. Since it's an Italian work, you

could combine it with Lo Speziale of Donizetti, which is a comic work,

or L'Isola Disabitata by Haydn. There are many things that would

work. Once in Rome I did it with Oedipus Rex.

BD: Let me ask about The Flying Dutchman. Do you feel yourself

a Wagner conductor?

AD: Oh, yes. I feel myself a conductor. I don't go by being very specialized. I don't think one can do anything very well if one cannot do another thing very well, too. I would go even farther than that and say one must do many other things. But I still recall that recording [with George London, Leonie Rysanek, Giorgio Tozzi, and Karl Liebl]. It was done rather quickly and it was very exciting. I listened to it a couple of times. I never have time to listen to my past recordings much, but I did listen to the Dutchman and it was a good one.

BD: When you're doing a stage work in the theater, how much do you get involved with the stage-mechanics and with the story and the drama?

AD: With the stage-mechanics I don't get involved, but with the story and the drama very much. I'm very deeply involved with this and I talk about it with the singers and the stage-director. If there is no stage-director (as when doing a recording), then I do that part of the work directly with the singers.

BD: I just wondered how much the stage movements affect the way you handle the music.

AD: Oh I think very much indeed, and I hope also the other way around. I hope that the way we are doing the music will affect the staging. That's a mutual influence there.

* * * * *

BD: Do you enjoy making records?

AD: Oh very much. I always did. [Note: To

read an interview with his recording producer Wilma Cozart Fine, click here.]

BD: Is there any danger that the sound which is in the plastic is too perfect?

AD: (laughing) No. There is never a danger that anything is too perfect. The danger is always that it is too imperfect.

BD: What about people who listen to their recordings and then come to the concert expecting that same perfection?

AD: Listening to a recording is different than hearing the

work in a concert hall. One should never be too much addicted to the record.

The real thing is to be there and hear the music and make the music. The

record is really a photograph of a performance, and you criticize a photograph

differently than you criticize a real person. A photograph has to be sharp,

and if you see a strand of hair moving the wrong way it has to be corrected.

But perhaps you see the person a little bit dim because your eyes are a little

bit dim, and then you see a strand of hair moving a little bit, that is very

good because that person made a movement which fits that or provokes that.

Recording is a secondary aspect of music; it is not primary.

AD: Listening to a recording is different than hearing the

work in a concert hall. One should never be too much addicted to the record.

The real thing is to be there and hear the music and make the music. The

record is really a photograph of a performance, and you criticize a photograph

differently than you criticize a real person. A photograph has to be sharp,

and if you see a strand of hair moving the wrong way it has to be corrected.

But perhaps you see the person a little bit dim because your eyes are a little

bit dim, and then you see a strand of hair moving a little bit, that is very

good because that person made a movement which fits that or provokes that.

Recording is a secondary aspect of music; it is not primary.

[Photo at left: Receiving a Gold Record for 1812 Overture]

BD: I'm just wondering if the public has made recordings the primary way they listen to music.

AD: That's too bad. They have to get rid of that notion.

BD: How do we get more people into the concert halls and opera houses?

AD: That is not my realm. We musicians can only do that by doing our best and giving fine performances. We don't have anything directly to do with ticket sales. The matter of getting a public to this or that performance or function has become a rather spurious business. You can whip up enthusiasm and ticket sales if you know how to do that.

BD: Is music becoming too much a business?

AD: Musical business, perhaps so.

BD: Don't you enjoy the extra enthusiasm which is generated by publicists?

AD: If it is the right kind of publicity, I have nothing against it. But it shouldn't take the place of the production.

BD: Let me ask about your Graduation Ball.

AD: That was so long ago I'll have to search a bit in my memory. A young choreographer had this story and presented it to me and asked me to do some kind of musical score to it. So I took a couple of melodies by Johann Strauss and made a ballet of it. It was a very charming thing and it's lasted a long time. That's now 40 years old, a pretty old gentleman.

BD: Do you feel that rock 'n roll is music?

AD: Well, it uses musical sounds. The question is a very complicated one. You could ask me if electronic music is music. I don't know; I can't tell you. I have a very great feeling that we are living in a time of schisms in which there are new arts of sound coming into being which are not music, but for which we have no name yet.

BD: Is it a mistake, then, for composers to try and incorporate these new sounds into their music?

AD: Oh no, by no means. Every new addition is an enrichment.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

AD: Oh yes. I am altogether optimistic about human life, and music is a very integral part of human life as far as I am concerned, and I think, unbeknownst to them, to mankind. Therefore, I think we, as human beings, have a future, so music does, also.

BD: I thank you for all of your performances and your recordings, and for spending this time with me today.

AD: It's very kind of you. In the time that is allotted to me, I hope that I can deserve it a little bit.

=== === === === ===

--- --- ---

=== === === === ===

| The conductor and composer Antal Doráti was one of

the most distinguished musicians of the 20th century.

In 1963 he was appointed Chief conductor of the BBC Orchestra, a post he held for 4 years. This was followed by a similiar position with the Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra (from 1965-1972). Parallel to his European activities he became music director of the National Symphony in Washington in 1970, followed by the same position 1977 in Detroit. At the same time (since 1975) Antal Doráti accepted the Royal Philharmonic's invitation to become their chief conductor. From 1981 he became "Conductor Laureate" for life of 3 orchestras (RPO London, Stockholm Philharmonic and Detroit Symphony). Antal Doráti's recording activities commenced in 1936, his total number of recordings reached nearly 600. Many of them won international prices, amongst others 32 "Grand Prix". His most important recording project was the complete recording of the 107 Haydn symphonies and 8 of the composer's operas. Antal Doráti's influence in the musical world has been highly significant, not only as a conductor. He has an impressive number of compositions to his credit, which are performed worldwide more and more. His teaching activities include regular masterclasses at the Royal College of music in London as well as at the Music Academy in Budapest. Both institutions made him their honorary member. Also masterclasses at the Salzburg Festival, Dartington and Bern - Basel are mentionable.

His distinctions included the post of Honorary President of the Philharmonia Hungarica, four honorary doctor degrees, the rank of Chevalier of the order of Vasa of Sweden, the Cross of Honour, 1st class "Artibus et Litteris" of Austria, the order of "Chevalier des Arts et Lettres" de France and others. The Royal Academy of Music in London honoured Antal Doráti by appointing him an Hon.R.A.M. And in 1983 her Majesty the Queen appointed him an Hon. KBE (Knight of the British Empire) in recognition for his service to music in Britain. Antal Doráti died in his Swiss home in Gerzensee on November 13, 1988. For more information, including complete lists of his compositions and recordings, as well as a few of his paintings, contact the Official Homepage of Antal Doráti . There was also a website for The Antal Doráti Centenary

Society. |

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This interview was held on the telephone on November 3, 1985.

Portions of the interview, along with musical recordings, were used on WNIB

several times thereafter. This transcription was made, and material

from it was used in an article which was published in the WNIB Program Guide

in April, 1986, celebrating his 80th birthday. The complete interview

was posted on this website in February, 2007.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about

his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full

list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the

photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with

comments, questions and suggestions.