A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

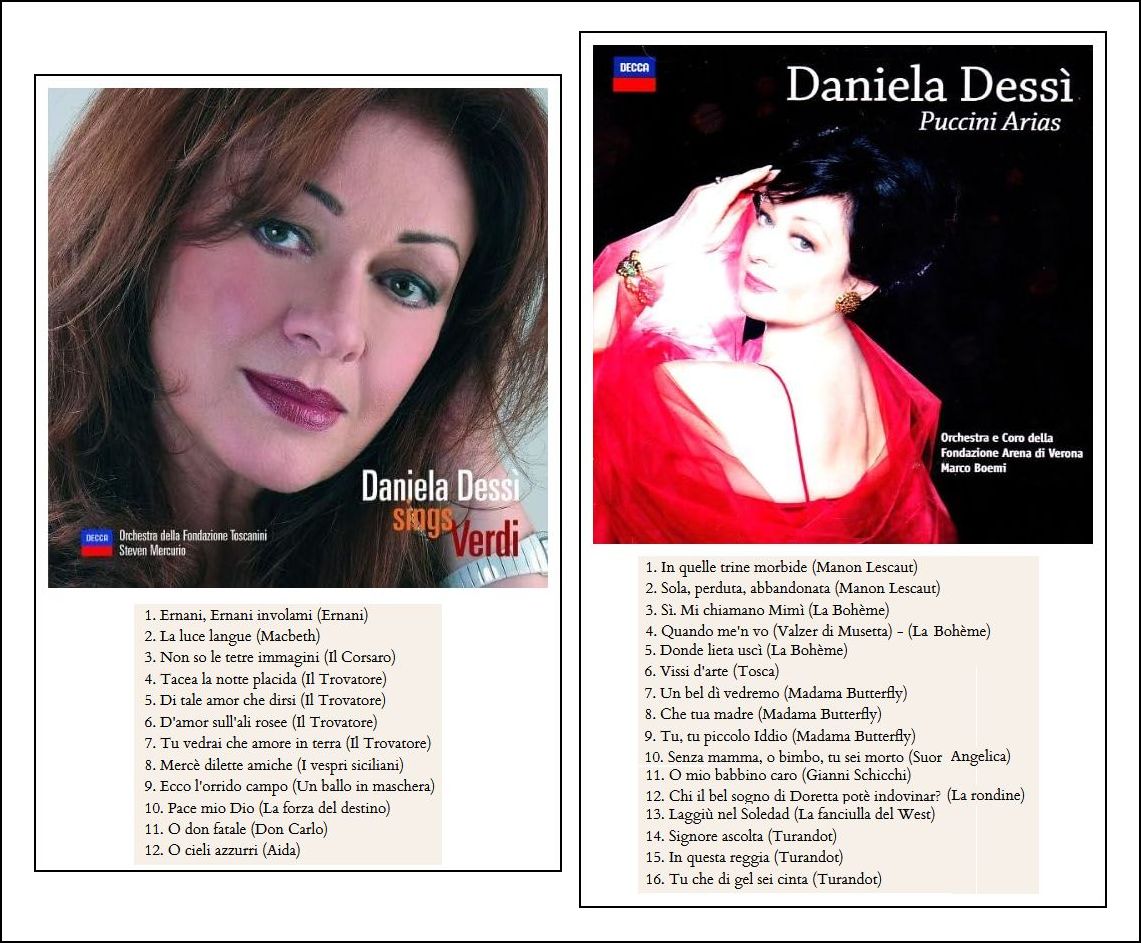

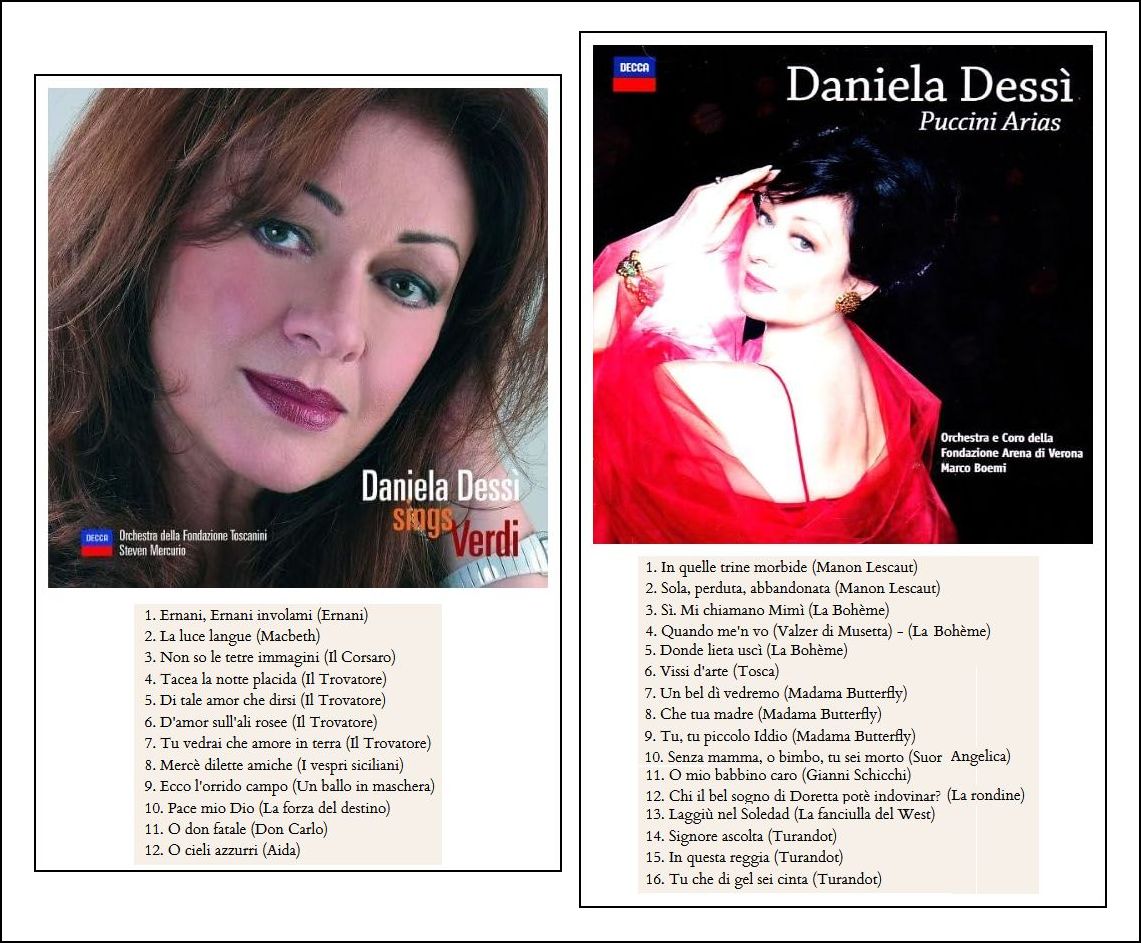

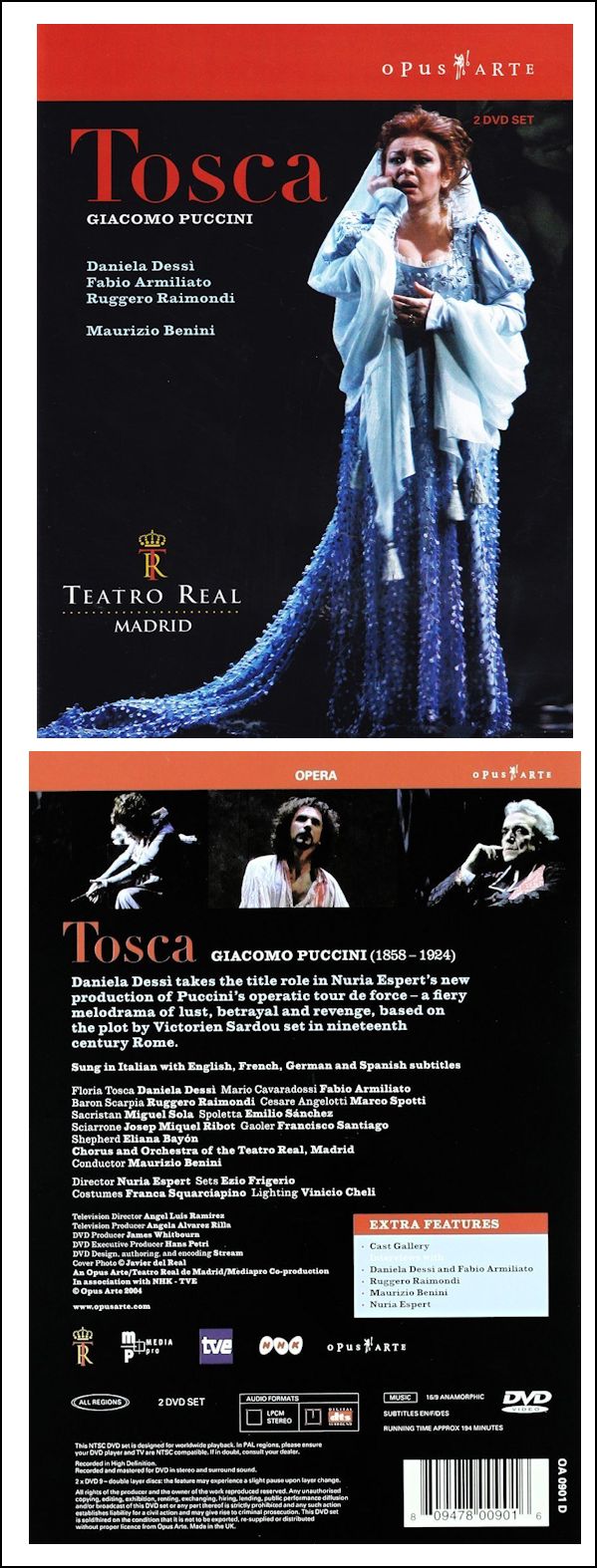

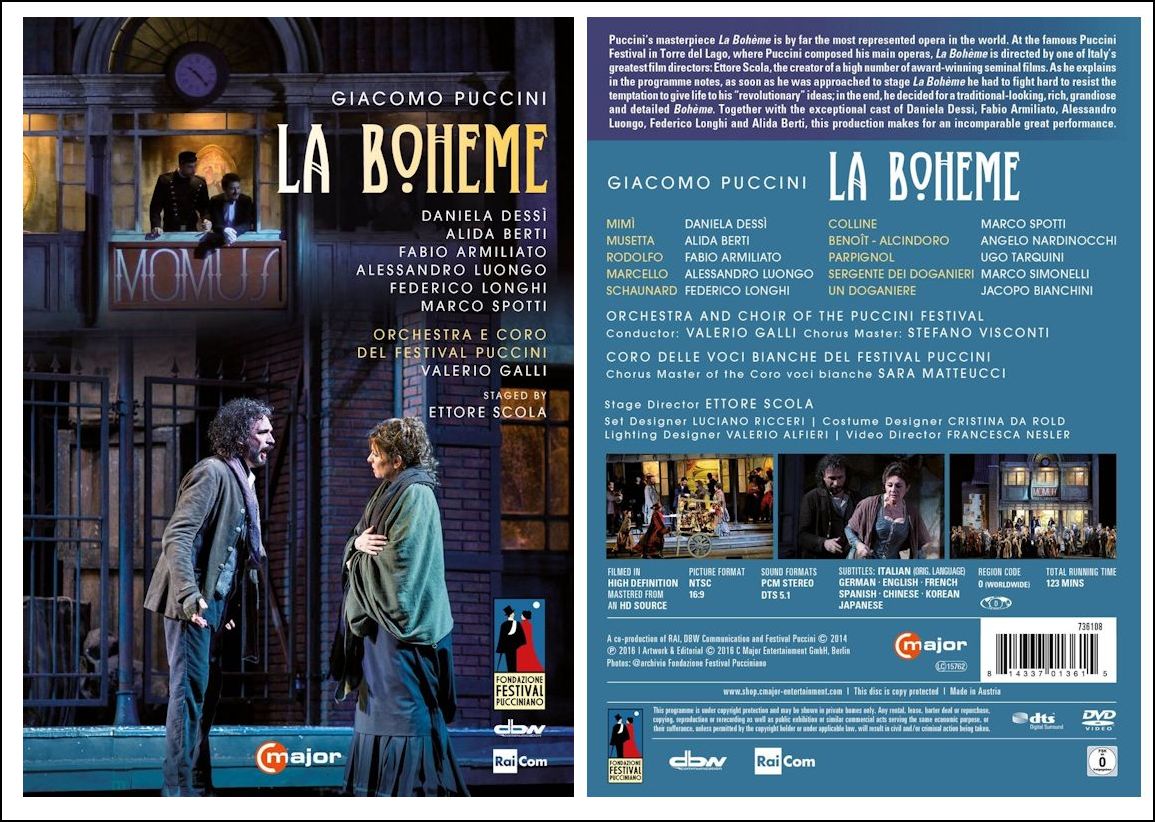

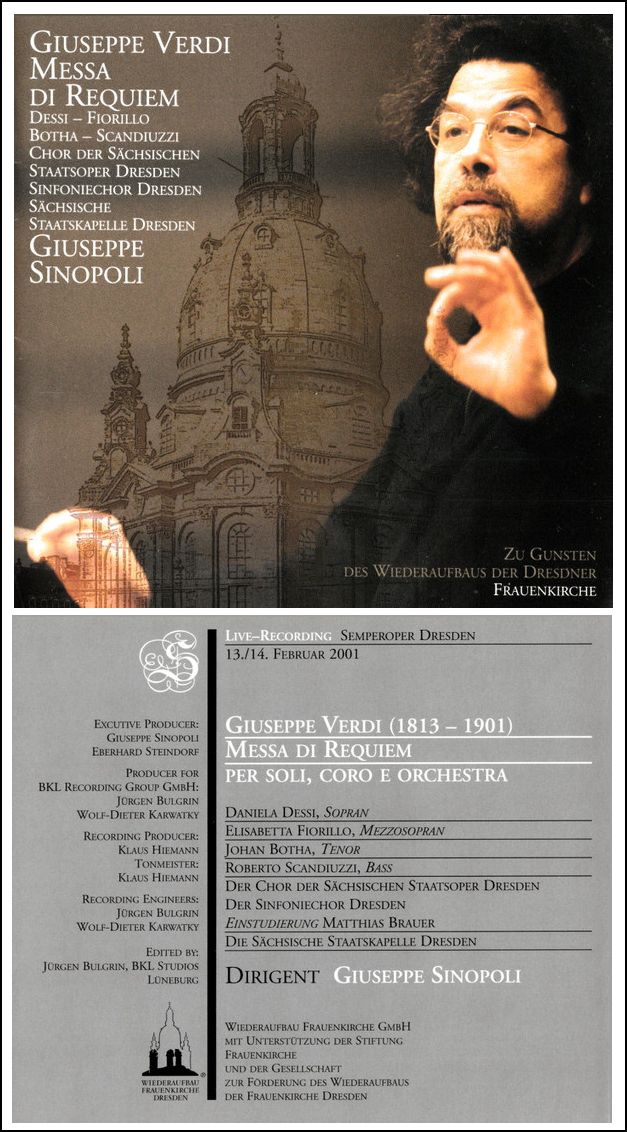

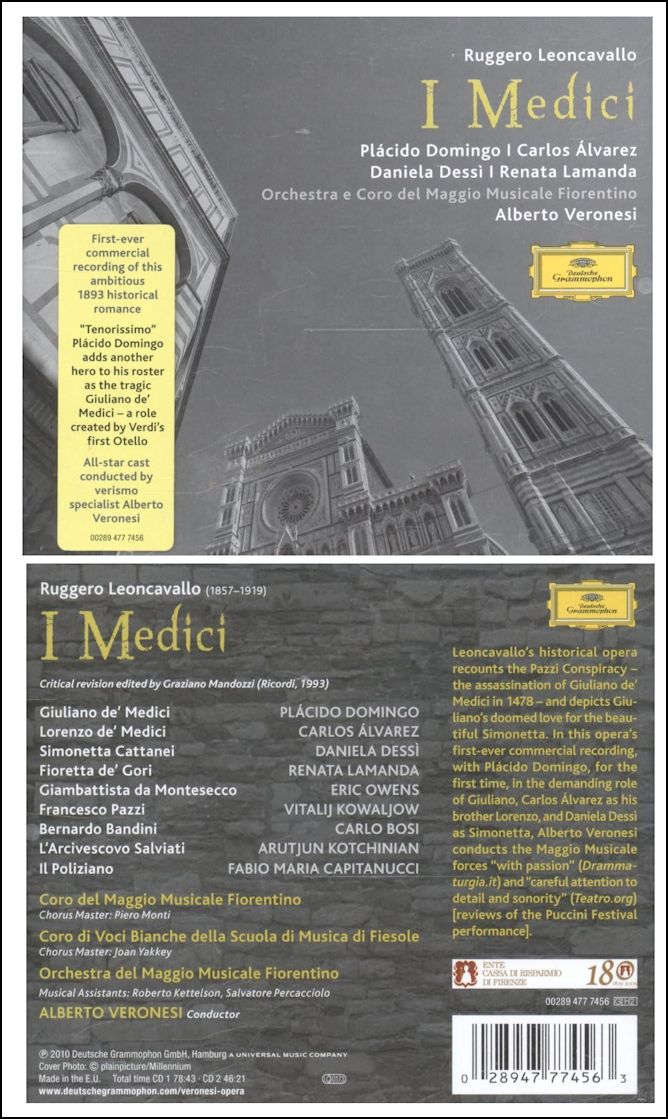

Daniela Dessì (May 14, 1957 - August 20,

2016) is considered one of the world’s leading sopranos and a reference

point for the Verdi, Puccini and Verismo repertoire. Thanks to the beauty

of her voice, a strong technique and an intense dramatic talent, she has

been able to sing from Monteverdi to Prokofiev, performing in more than

seventy different operas. This versatility has significantly been underlined

when, in 2011, she was awarded with the Prize Belcanto “Celletti”, recognized

as an “absolute soprano”. Born in Genoa, she graduated in singing and in piano from the Conservatory “Arrigo Boito” in Parma, later specializing in chamber singing at the Accademia Chigiana in Siena. Since her debut in La Serva Padrona by Pergolesi in Genoa, her career started taking wing. Requested in the world major opera houses and festivals, she has collaborated with great conductors such as Claudio Abbado, Riccardo Chailly, Daniele Gatti, Gianluigi Gelmetti, Carlo Maria Giulini, Carlos Kleiber, James Levine, Lorin Maazel, Zubin Mehta, Riccardo Muti, and Giuseppe Sinopoli. She has worked with the most famous directors, including Roberto De Simone, Pier Luigi Pizzi, Luca Ronconi, Ettore Scola, Giorgio Strehler, Franco Zeffirelli. It is worth highlighting the breadth of Daniela Dessì’s repertoire. It ranges from Baroque and Eighteenth-Century music (with the great interpretations of Don Giovanni, Le Nozze di Figaro, Così fan tutte and La Clemenza di Tito by Mozart with Riccardo Muti conducting) to the works of the early Twentieth Century, mainly focusing on the glorious Nineteenth Century Italian operatic composers (Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti and Verdi). Complying with her vocal evolution, Daniela Dessì has quickly succeeded in establishing herself as one of the leading interpreters for Verdi, Puccini and Verismo. As a matter of fact, she has been the first Italian singer to perform in her country the three roles of Puccini’s Trittico (Giorgetta, Suor Angelica and Lauretta) in the same evening; she has also been the first and only Western soprano to perform Madama Butterfly in Nagasaki, in Japan, on occasion of a tour arranged by the Festival Pucciniano, Torre del Lago. == From the website of the Georg Solti Academia (where

she was on the faculty in 2013) [with addition of her birth/death dates]

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1999 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 15, 1999. Portions were broadcast on WNIB four days later. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to Marina Vecci of Lyric Opera for providing the translation duirng our interview. Also, my thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.