A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

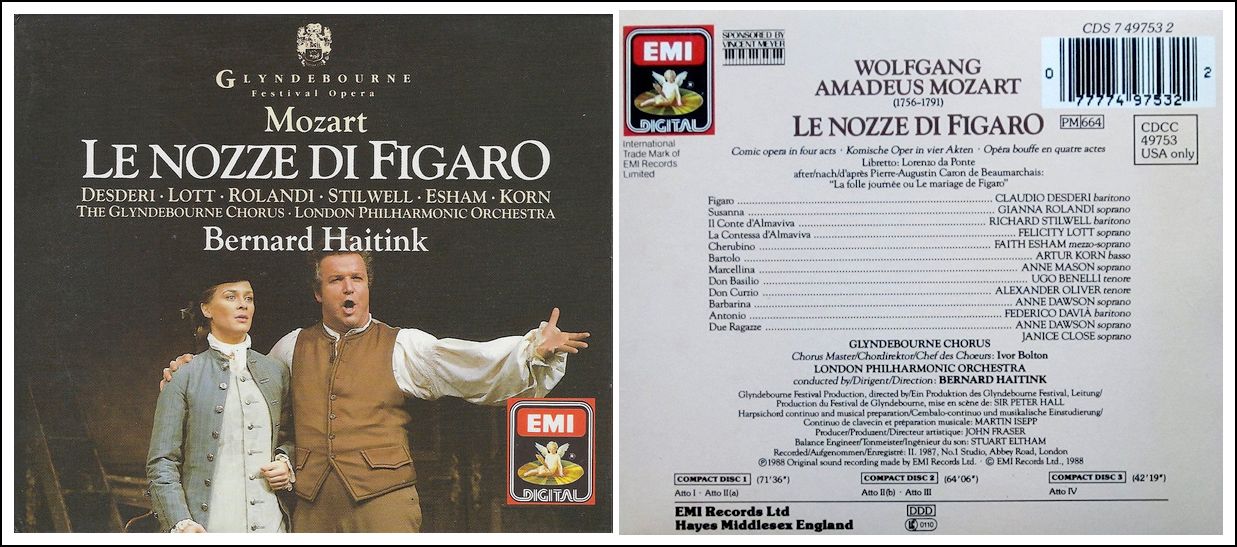

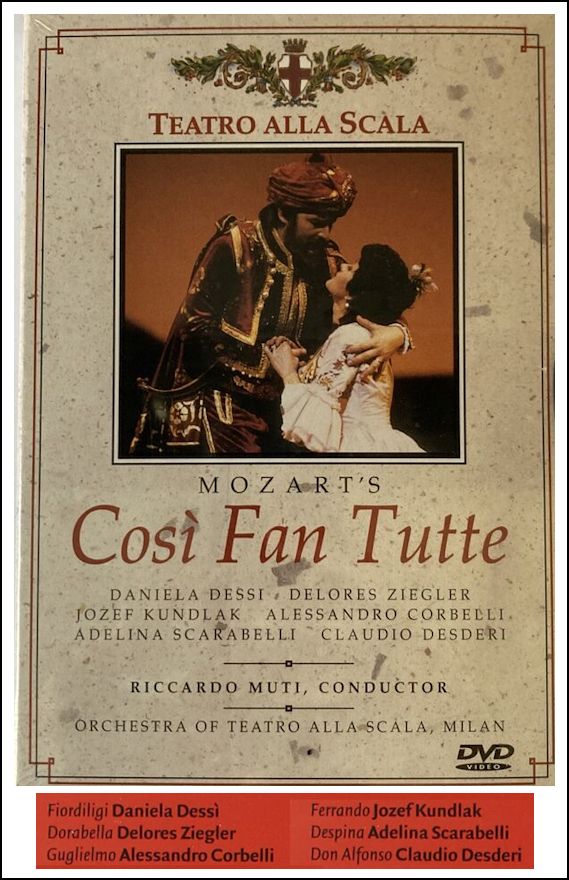

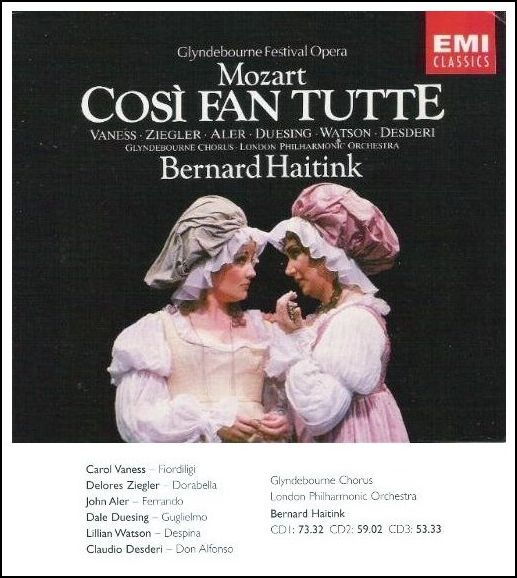

See my interviews with Gianna Rolandi, Richard Stilwell, Felicity Lott, Faith Esham, Bernard Haitink and Sir Peter Hall

|

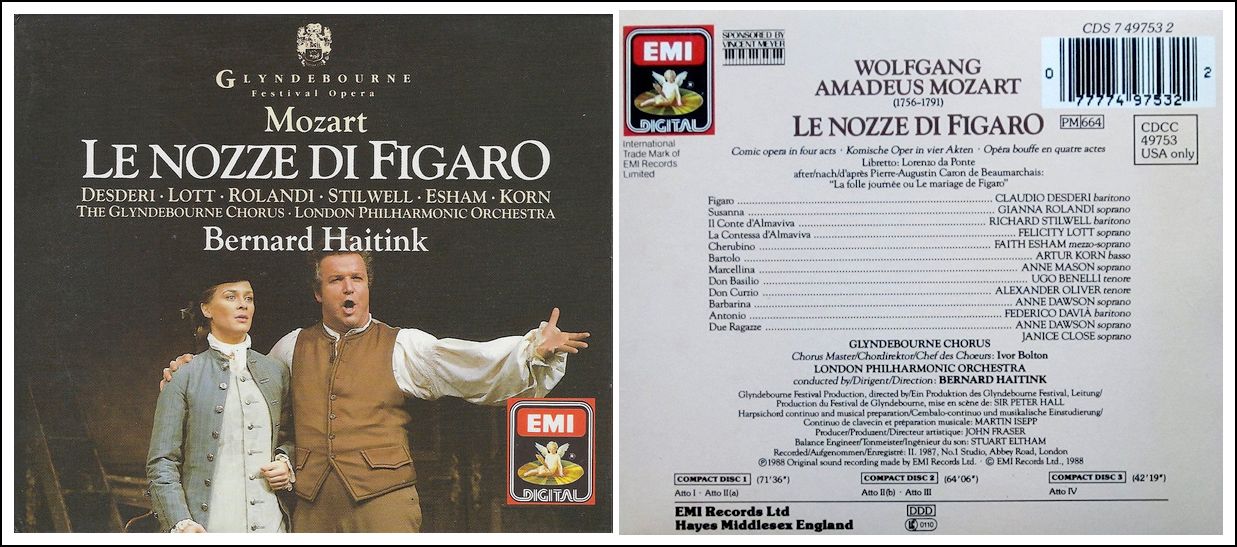

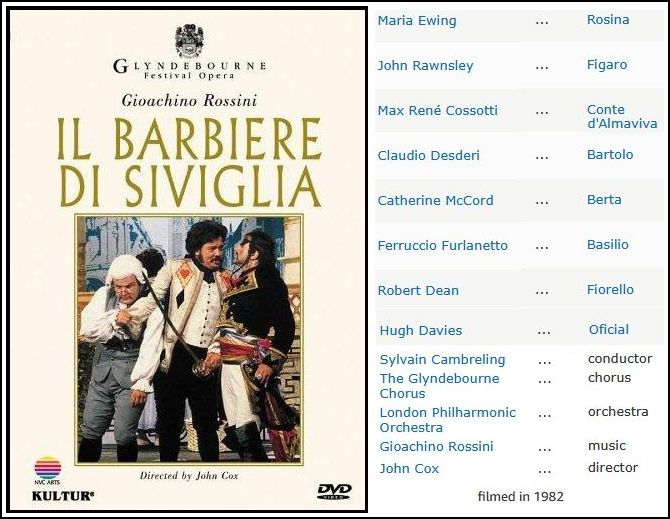

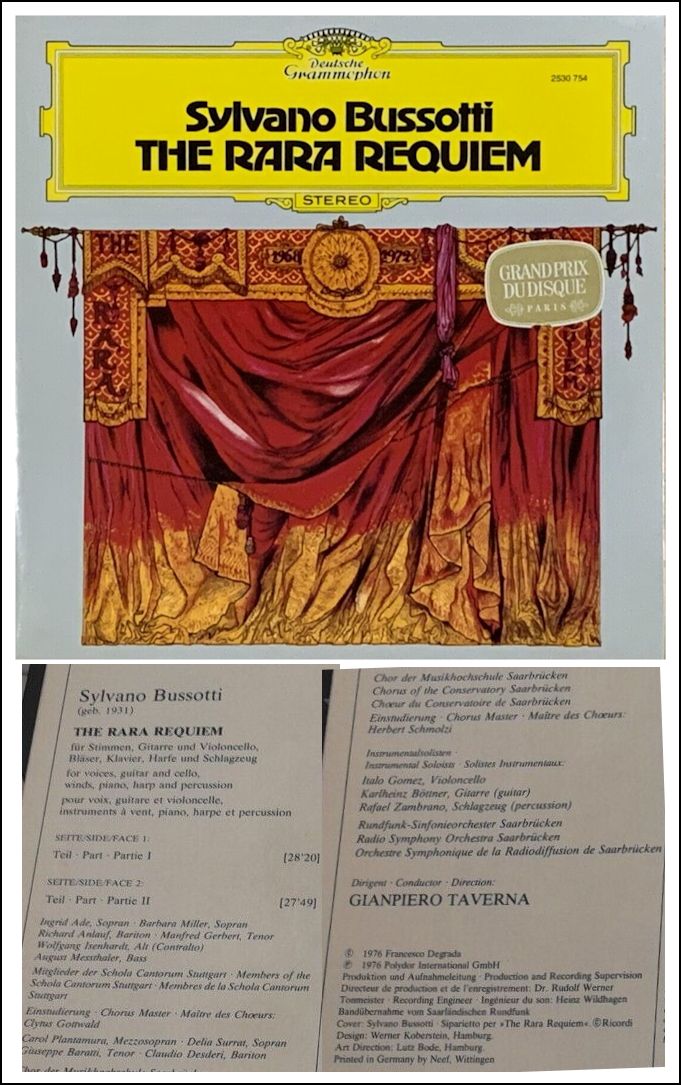

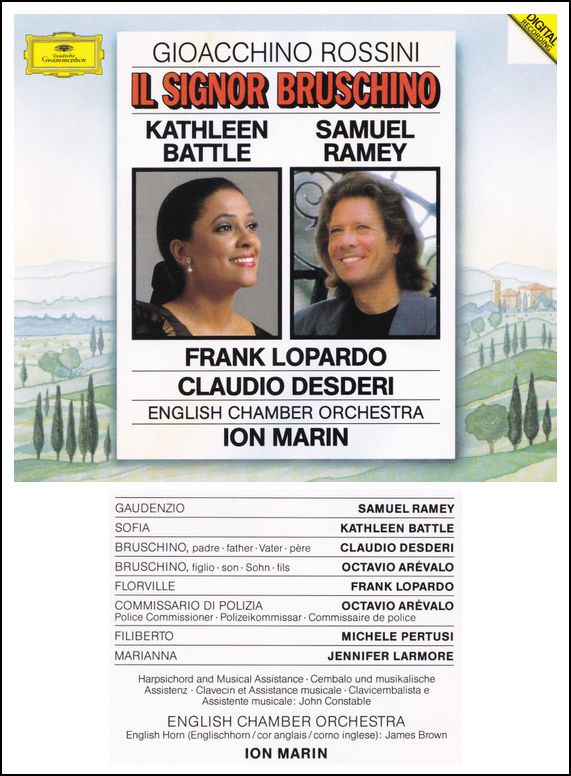

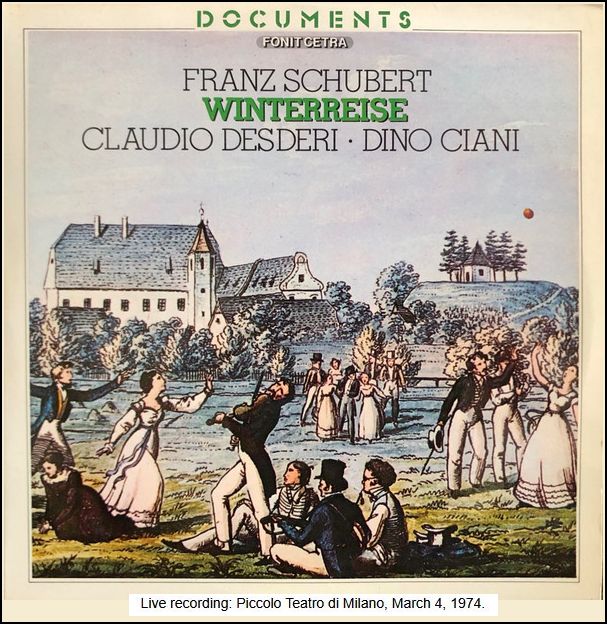

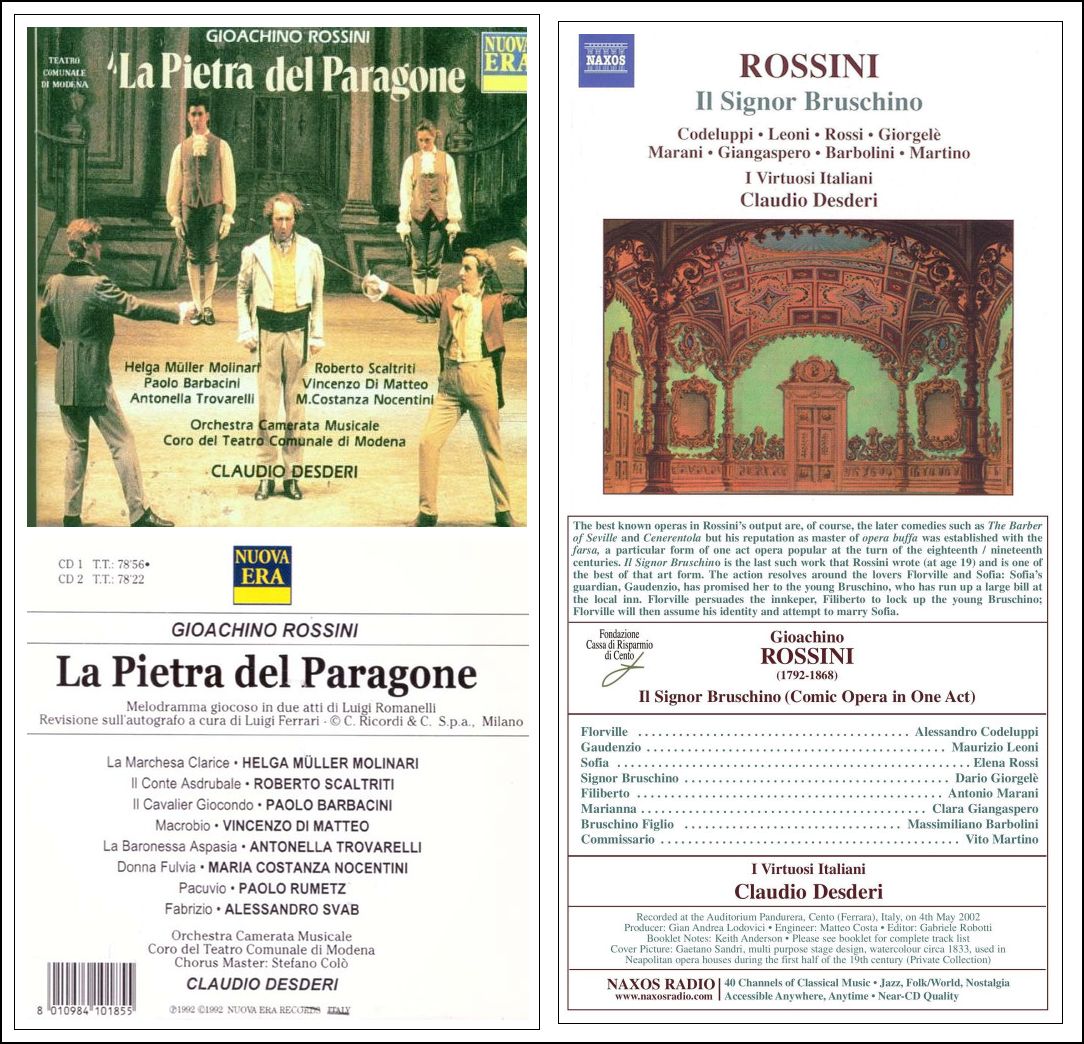

Claudio Desderi (April 9, 1943 in Alessandria - June 30, 2018 in Florence), known for his buffo roles, was the son of Italian composer Ettore Desderi, and came to fame after his 1969 debut at the Edinburgh Festival in Rossini’s “Il Signor Bruschino.” From there he became a fixture at Salzburg, Glyndebourne, and Pesaro in Mozart and Rossini roles. At La Scala, Milan, he sang in “La Cenerentola” and “l’Italiana in Algeri,” conducted by Claudio Abbado and directed by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle. He would also perform Mozart’s Da Ponte trilogy conducted by Riccardo Muti and directed by G. Strehler. After retiring from his singing career, he would become the artistic

director of the Teatro Verdi from 1991 to 1998 and the Teatro Regio from

1999 to 2001. He would also become the superintendent of the Teatro

Massimo from 2002 to 2003. He was also a formidable teacher. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

Claudio Desderi at Lyric

Opera of Chicago

1977 Barber of Seville (Bartolo) - with Stilwell, Ewing, Alva, Montarsolo, Hynes, Andreolli; Bellugi, Gobbi, Peter J. Hall 1983 Cenerentola (Don Magnifico) - with Baltsa, Blake, Nolen, Harman-Gulick, Sharon Graham, Crafts; Ferro, Ponnelle 1988-89 Don Giovanni (Leporello) - with Ramey, Vaness, Mattila, Winbergh, McLaughlin, Cowan, Macurdy; Bychkov, Ponnelle 1989-90 Barber of Seville (Bartolo) - with Allen, von Stade, Lopardo, Ghiuselev, Lawrence; Pinzauti, Copley, Conklin 1991-92 L'elisir d'amore (Dulcamara) - with Gasdia, Hadley, Corbelli, Futral; Pappano, Chazalettes, Santicchi 1993-94 Così fan tutte (Don Alfonso) - with Vaness/Magee, Ziegler, Rolandi, Lewis, Black; Davis, Sir Peter Hall 1994-95 Barber of Seville (Bartolo) - with Allen/Braun, von Stade/Mentzer, Blake, Ghiaurov/Halfvarson; Rizzi/Behr, Copley, Conklin 1996-97 Un Re in Ascolto [Berio] (Friday) - with Lafont, Harries, Rambaldi, Devlin, Begley, Woods, Langton; Davies, Vick, Dyer |

© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on December 19, 1991. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1993. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.