|

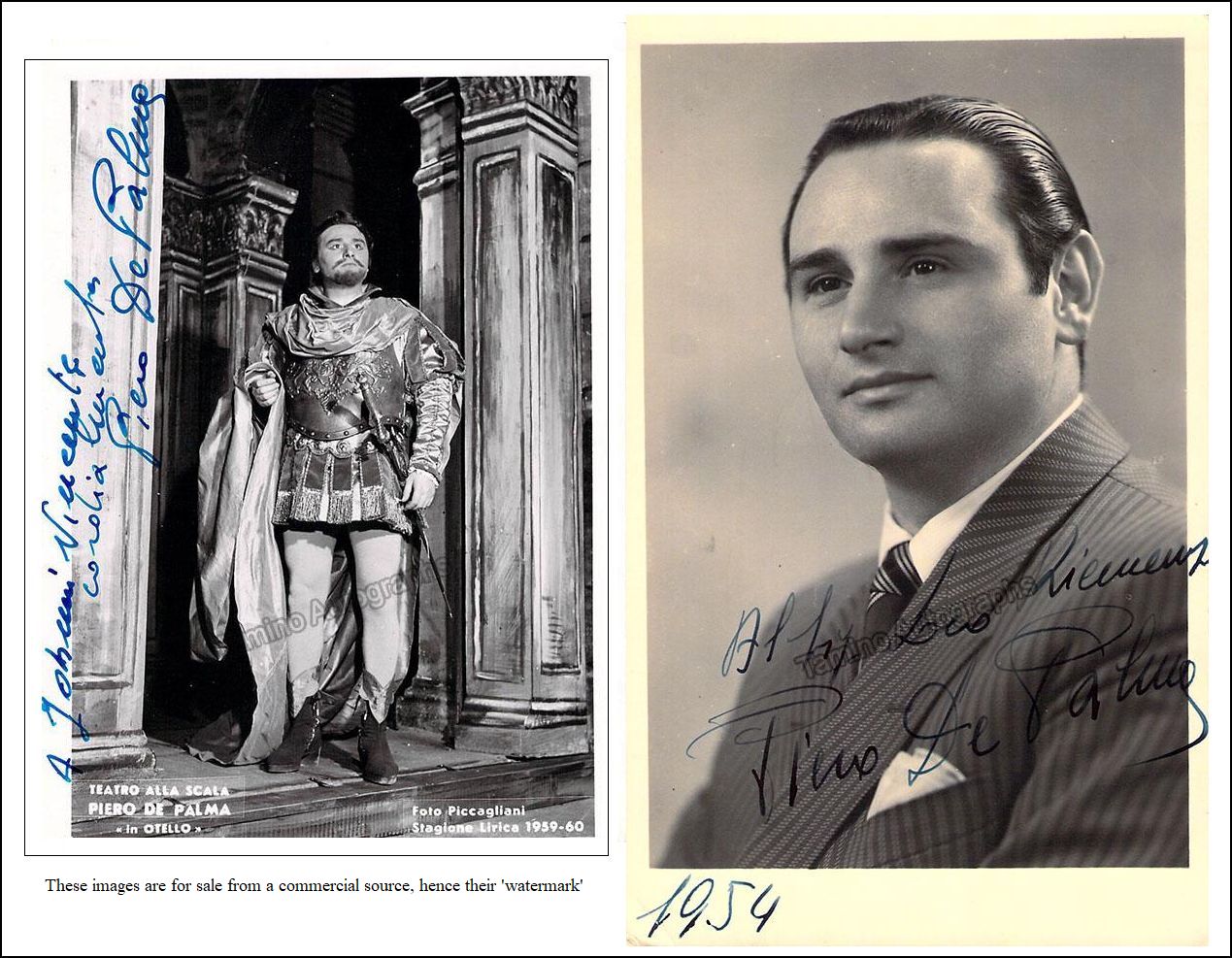

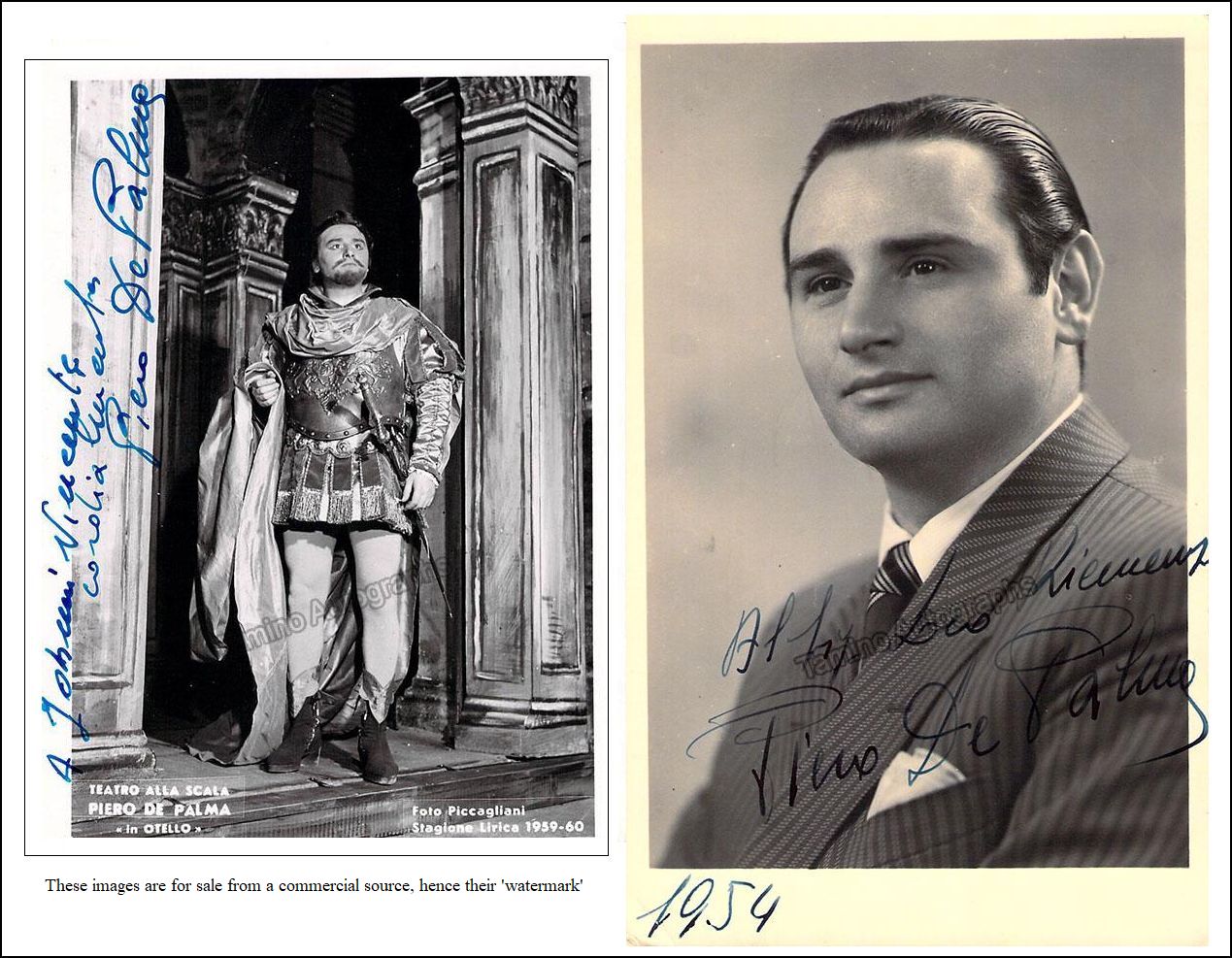

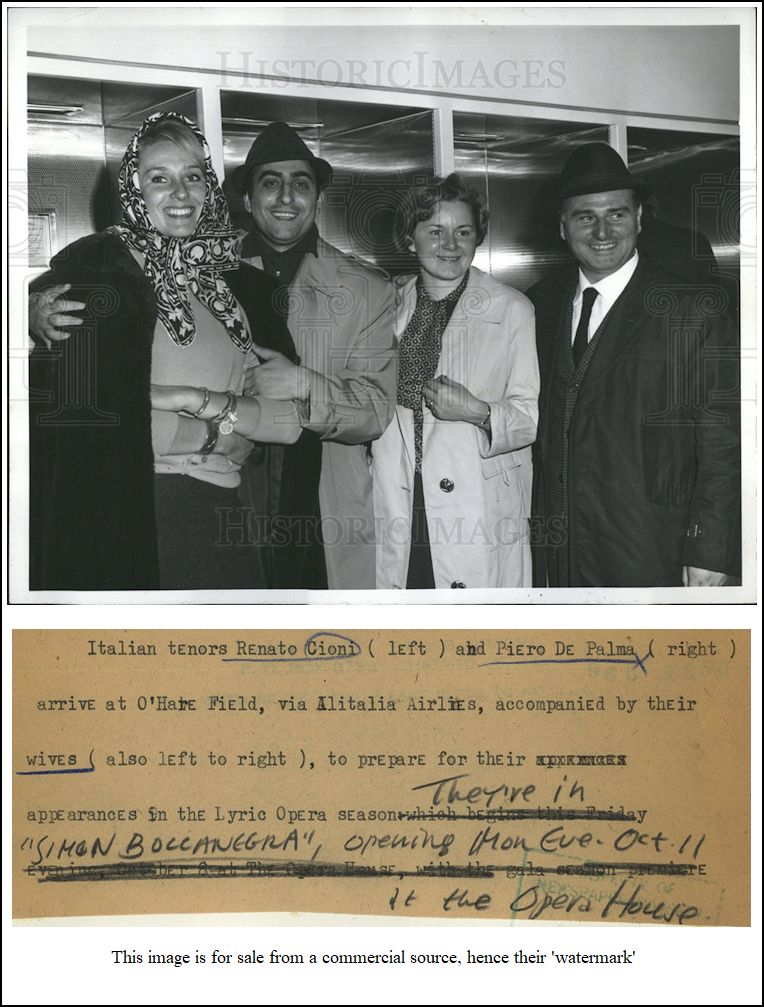

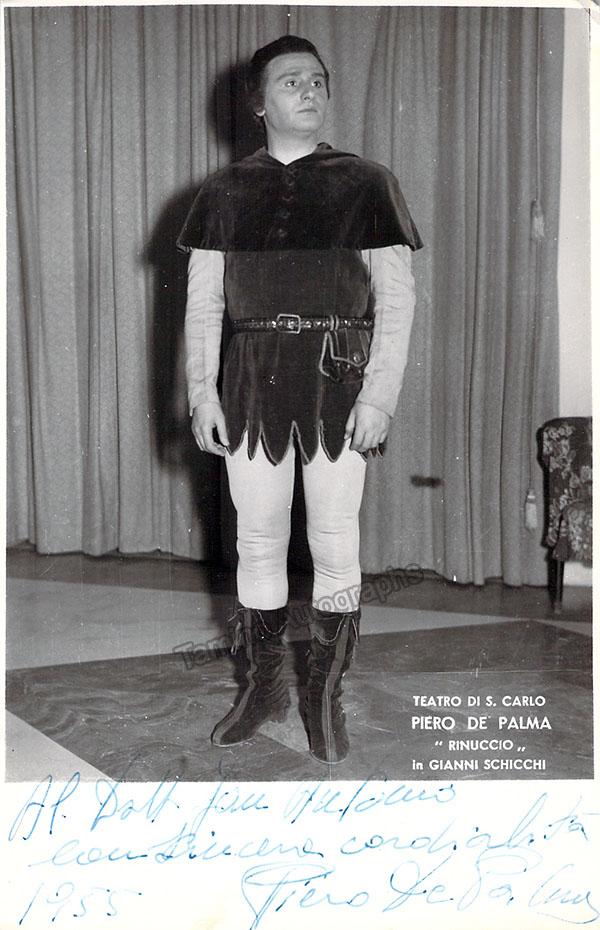

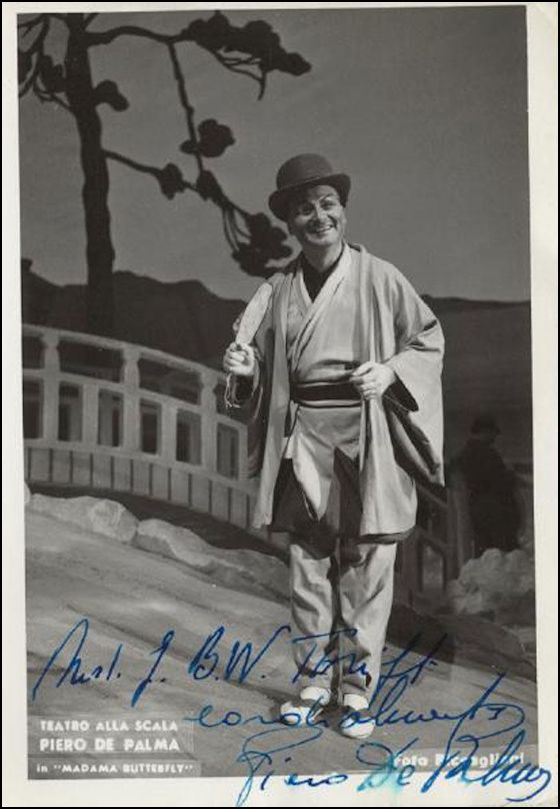

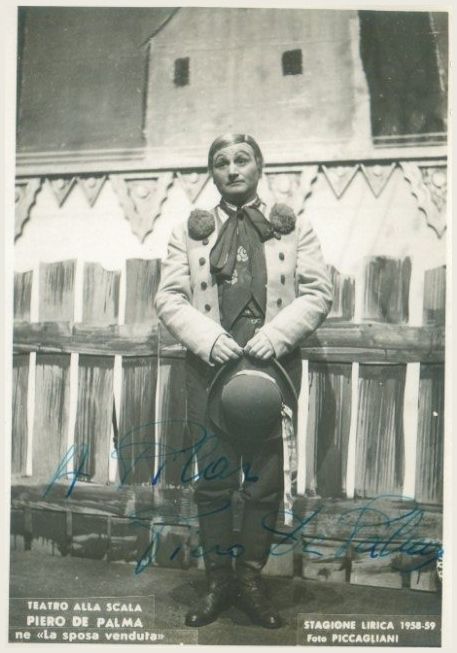

Piero De Palma (31 August 1925 – 5 April 2013) was an Italian operatic tenor, particularly associated with comprimario roles. After choral and concert work, he began his operatic repertoire career in 1948 by singing on Italian radio (RAI). He made his stage debut in 1952 at the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, where he performed regularly until 1980. The same year saw his debuts at the Rome Opera and the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino. He then went on singing throughout Italy, appearing in Genoa, Palermo, Catania, Trieste, and Bergamo. He also appeared at the Baths of Caracalla and the Verona Arena, and made his debut at La Scala in Milan in 1958. He performed for numerous seasons regularly at The Dallas Opera, and made his Metropolitan Opera debut as Dr. Cajus in Falstaff in 1992. He made a specialty of character roles, and became perhaps the finest

and most famous of all postwar comprimario artists. He possessed a fine

voice and was an outstanding actor. He sang an estimated 200 roles throughout

his career, among his most famous were Dr. Cajus in Falstaff and Pong

in Turandot. Other notable roles included Basilio, Normanno, Malcolm,

Borsa, Gastone, Cassio, Spoletta, Edmondo, Goro, and Spalanzani. He sings

on over 130 opera recordings from the 1950s to the 1980s, including multiple

recordings of operas in different roles, e.g., Pong, Pang, and the Emperor,

in various recordings of Turandot. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

© 1992 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 31, 1992. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1998. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to Marina Vecci of Lyric Opera for translating, and to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.