| [Posted Monday, November 30, 2009] Richard Cumming

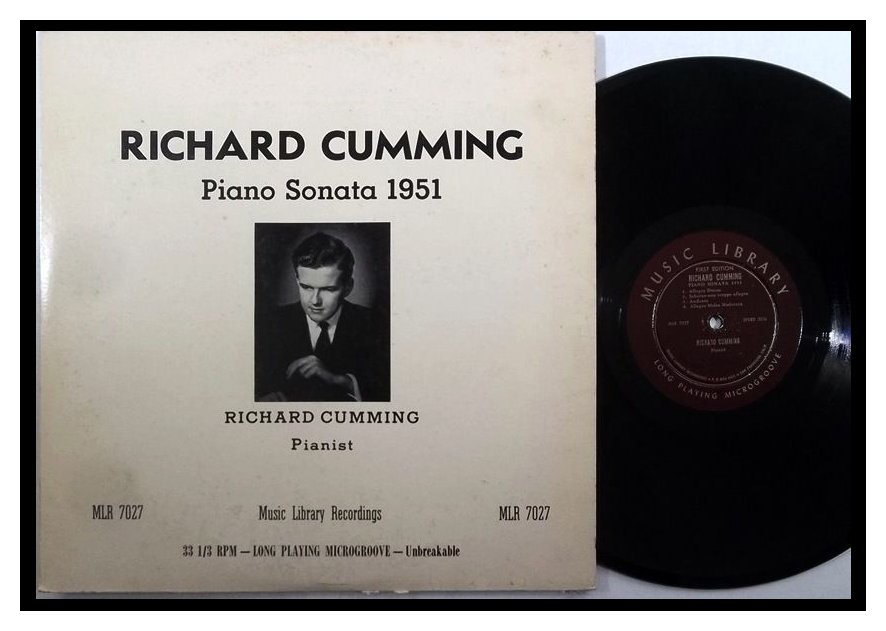

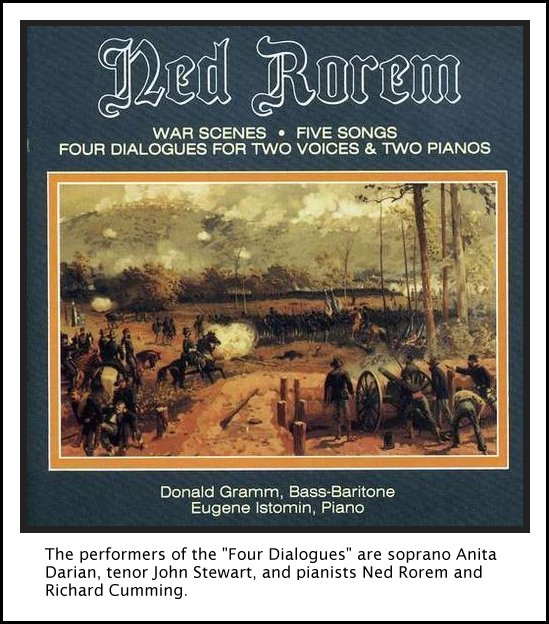

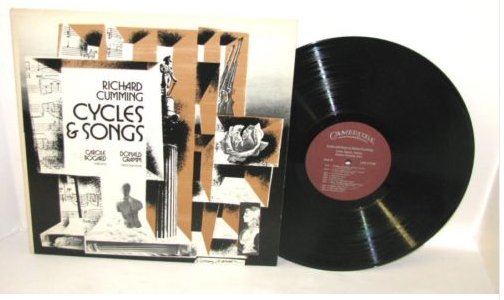

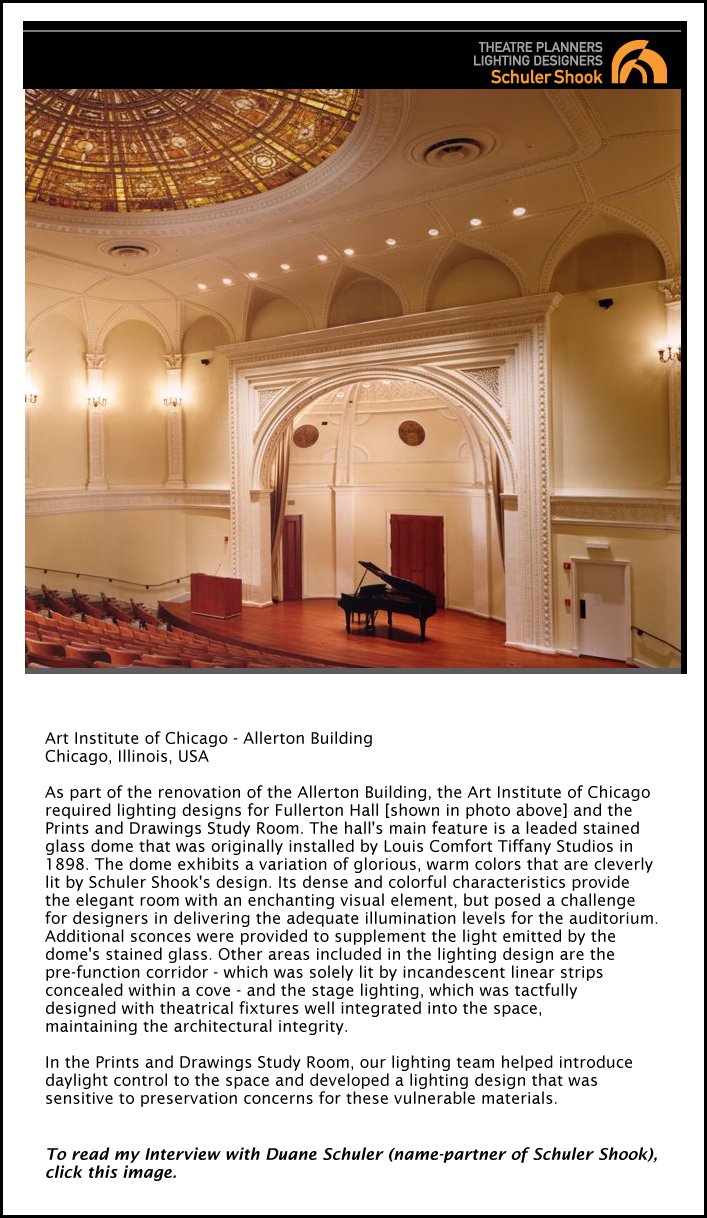

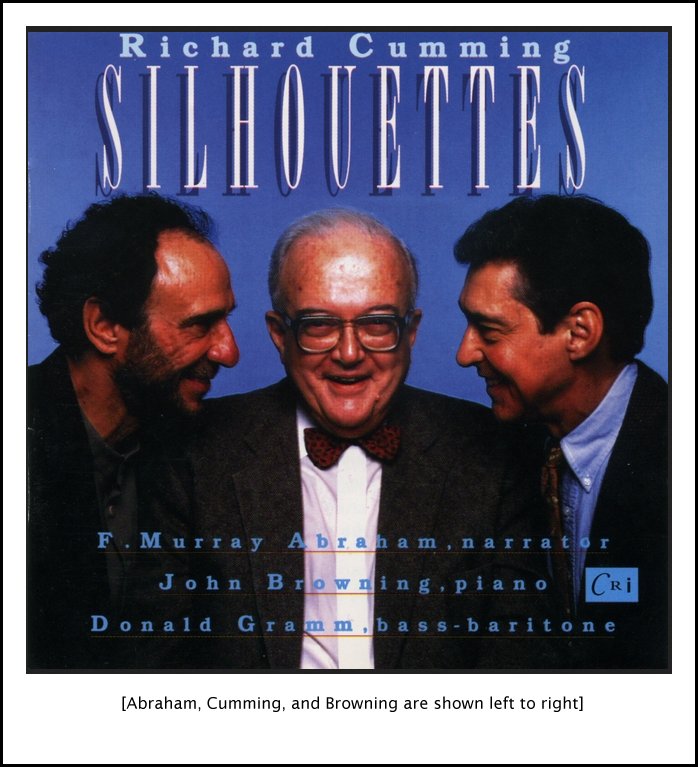

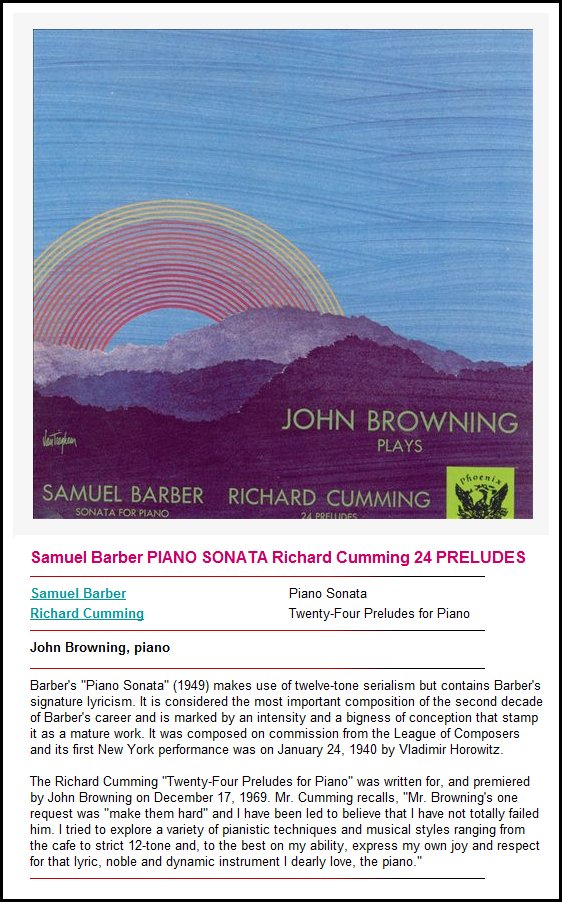

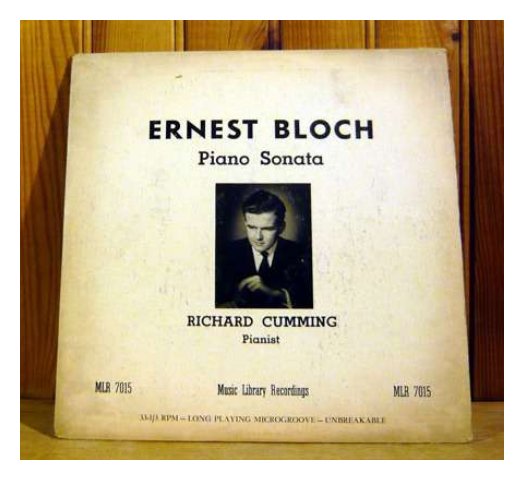

(June 9, 1928 - November 25, 2009) My cousin, Richard Cumming (known to friends and family as Deedee) died on Wednesday, at the age of 81. He was a composer, pianist, teacher, and for 25 years, the composer-in-residence at the Trinity Repertory Company in Providence, Rhode Island. Deedee would be known to Hartford audiences for two works the orchestra performed. Passacaglia was presented on the (now defunct) Rush Hour series several years ago. I commissioned the work when I was still a student at the University of California, Berkeley, and needed another short work to fill out a noon concert program that included Brahms's Serenade no. 2 for small orchestra. Not wanting to be accused of blatant nepotism (of which Deedee loved to say, "it's okay, dear, as long as you keep it in the family. . ."), I was going to leave it at that, but after a number of players and audience members remarked to me how much they liked Deedee's Passacaglia, I kept my ears to the ground for another work from his pen; when he told me that his Aspects of Hippolytus was looking for a first performance, I jumped at the chance, and the HSO presented the work on its Masterworks series. Richard Cumming's music was always unabashedly tonal, well before it was de rigeur to write that way. In the 1950s and 1960s, most classical composers wrote music that could be terribly forbidding, and many didn't care whether you liked their music or not. Only with the advent of Minimalism from Messrs. Riley, Glass, Reich and Adams did classical music begin to become more accessible -- but Deedee was there long before them. The great American pianist, John Browning (1933-2003), recorded Deedee's 24 piano preludes, then later his Silhouettes. Browning and Cumming were close friends as well as great colleagues; John premiered Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto in 1962. (I had hoped to bring him to Hartford to perform the work.) Deedee told me, "Sam was taking his time on the concerto, even though a number of us kept reminding him that John needed time to learn it before the premiere. Well. . . damned if Sam didn't get the finale [which is excruciatingly difficult -- ec] done just a week or two before the concert date, but John being John, he did the whole work, and the finale, from memory." Deedee was scary smart, with a wonderful command of the English language. Books surrounded his apartment in Providence, and when I asked him if he'd read them all, he quickly responded, "yes, most of them 2 or 3 times." If a fine writer were to take up the project of writing a Richard Cumming biography, it would be a great read, if only for the stories. He had a laugh that could easily fill a room. Even when he was cranky or irritated, he seemed to be smiling; any room he entered was quickly filled with his mirth. He was a fabulous pianist, touring the world in recital with the soprano, Phyllis Curtain (1921 - ). The late bass-baritone, Donald Gramm (1927-83, who was known for his brilliant portrayal of Boris Godonov at the Met), was another singer who worked regularly with Deedee. He studied with Roger Sessions, and Ernest Bloch was a musical grandfather to him. When Arnold Schoenberg gave composition classes in Los Angeles, Deedee signed up. (It drove the other students crazy with envy that Schoenberg referred to all of them by their surname -- except for Deedee.) Time spent with Deedee was invariably a learning experience. One time he recounted a story of his time on tour with Igor Stravinsky. I think Deedee began the stint as his musical assistant, but ended up doubling as his valet, making sure he had plenty of vodka in his room. Like so many Russian men, Igor liked the hard stuff, and Deedee was a good drinking buddy. (I think his daily vodka and milk on the rocks -just before bedtime- was introduced to him by Stravinsky.) I first met Deedee (technically speaking, my first-cousin-once-removed) 35 years ago, when I was a horn player with little design on becoming a conductor. He was as tall as me, but bigger, somehow, contributing to his larger than life persona. He asked me if I'd like to play something with him; I suggested the Hindemith Horn Sonata, and he played the difficult piano part brilliantly, at sight. I was awestruck. . . this guy is a relative of mine? Where did he come from, and why didn't anyone in my family tell me anything about him before that day? The fact that he was homosexual (and openly so) might have had something to do with that, long before it was remotely socially acceptable, even in the most liberal cultural circles. What I will always take with me, though, is the music he introduced to me. Strauss's Elektra. Barber's Knoxville: Summer of 1915. Ned Rorem's song cycle, Flight from Heaven. When I got to 'Upon Julia's Clothes,' Deedee began screaming, "Is that not the best song of the 20th century? Damn! I wish I'd written that. . ." -- From a Blog, posted by Edward

Cumming at 12:26 AM, November 30, 2009

[To read more about Edward Cumming, click here.] -- Names which are links (throughout this webpage) refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD |

Bruce Duffie: [Before actually beginning]

Let me get you some more water before we start.

Bruce Duffie: [Before actually beginning]

Let me get you some more water before we start. BD: Tell me the joys and sorrows of writing for

the voice.

BD: Tell me the joys and sorrows of writing for

the voice. BD: I take it you are basically pleased with

the performances of your works that you’ve been involved in, and the ones

you’ve heard?

BD: I take it you are basically pleased with

the performances of your works that you’ve been involved in, and the ones

you’ve heard? BD: You spent about thirty years of your life when

you and maybe a very select handful of others were the only ones writing tunes.

Had everyone lost this ability or desire?

BD: You spent about thirty years of your life when

you and maybe a very select handful of others were the only ones writing tunes.

Had everyone lost this ability or desire? RC: Oh, my God, it’s awash with it! [Both

laugh] Oh, sure! Oh, yeah, I’m a juicy composer. I write

twelve-tone pieces, too. The Preludes

are twelve-tone pieces. The D Major

is strict twelve-tone. It’s very funny, I think. People say,

“Oh, it’s such a moving piece,” and I say, “Well, I’m glad you’re moved.

I worked hard on it.” The G Minor

is based on a row and it’s treated very tonally, and that, oddly enough, sounds

very old fashioned now to me. I loved the G Minor when I wrote it. I thought,

“This is a really, really important piece.” Well, I don’t know that

it is. I really don’t care that it is. It’s been so long since

I’ve written those pieces, but it’s fun to hear them. I had a wonderful

experience last week or two weeks ago. I was looking for a piece that

I knew I had written. I knew I had written something, and between moving,

first from the west coast from San Francisco to New York, living for years

in New York and then pillar to post, and finally settling something in Providence,

Rhode Island, there’s still a lot of music in drawers somewhere. So

I thought, “Enough of this! You do

this every time you’re looking for something, and you know you wrote it, and

you know it’s around.” I went through and I spent

four days just taking everything out of the drawers and cataloging everything,

just putting them in folders and finally just putting the folders back in

alphabetical order. All the stuff that is printed or published or bound,

that’s fine. That’s on the shelf. That takes up three shelves.

We now have six drawers filled with, quite often, the originals of those

manuscripts and a lot of things are sketches. Be that as it may, one

thing I found, I’d written a symphony in the summer of ’57! It’s a

little symphony, but it’s a three-movement symphony, and I ran across it.

It’s all scored and it’s not bad! [Laughs] I was so pleased.

People kept saying, “When are you writing a symphony?” and I’d say, “Oh,

I don’t know. The symphony? I don’t think it’s dead but I don’t

think I’m ready to do one.” Well, I have written a symphony and I’m

very pleased with it. It’s very nice. I might re-do the second

movement. The first and third movements are very nice.

RC: Oh, my God, it’s awash with it! [Both

laugh] Oh, sure! Oh, yeah, I’m a juicy composer. I write

twelve-tone pieces, too. The Preludes

are twelve-tone pieces. The D Major

is strict twelve-tone. It’s very funny, I think. People say,

“Oh, it’s such a moving piece,” and I say, “Well, I’m glad you’re moved.

I worked hard on it.” The G Minor

is based on a row and it’s treated very tonally, and that, oddly enough, sounds

very old fashioned now to me. I loved the G Minor when I wrote it. I thought,

“This is a really, really important piece.” Well, I don’t know that

it is. I really don’t care that it is. It’s been so long since

I’ve written those pieces, but it’s fun to hear them. I had a wonderful

experience last week or two weeks ago. I was looking for a piece that

I knew I had written. I knew I had written something, and between moving,

first from the west coast from San Francisco to New York, living for years

in New York and then pillar to post, and finally settling something in Providence,

Rhode Island, there’s still a lot of music in drawers somewhere. So

I thought, “Enough of this! You do

this every time you’re looking for something, and you know you wrote it, and

you know it’s around.” I went through and I spent

four days just taking everything out of the drawers and cataloging everything,

just putting them in folders and finally just putting the folders back in

alphabetical order. All the stuff that is printed or published or bound,

that’s fine. That’s on the shelf. That takes up three shelves.

We now have six drawers filled with, quite often, the originals of those

manuscripts and a lot of things are sketches. Be that as it may, one

thing I found, I’d written a symphony in the summer of ’57! It’s a

little symphony, but it’s a three-movement symphony, and I ran across it.

It’s all scored and it’s not bad! [Laughs] I was so pleased.

People kept saying, “When are you writing a symphony?” and I’d say, “Oh,

I don’t know. The symphony? I don’t think it’s dead but I don’t

think I’m ready to do one.” Well, I have written a symphony and I’m

very pleased with it. It’s very nice. I might re-do the second

movement. The first and third movements are very nice. RC: If you have any thought that you might like

to do anything else, then by all means do something else. Composing

doesn’t get easier. The technical thing of being able to put notes down

on paper and knowing the ranges and instrumental difficulties and things like

that finally become second nature. Those things become easier.

Taste and choice, those very difficult things to even define become harder

and harder. Then there is the tyranny of that blank paper! There

are some mornings I just don’t want to do that three hours. I promise

you that I just don’t! But I do, and I really sit there. Being

an objective person, I don’t really like to waste time, and so the little

old mind starts working and something comes out. If nothing else, I’ve

got parts to copy, and nothing is more tedious that that. I’d rather

compose than copy parts. Oh golly, what advice? Just study!

Just know as much as you possibly can! The more tools one has — and

we’re in a position now that the tools are becoming available! I’m not

just talking of twelve-tones and aleotoric and repetition and minimalism.

We’re talking machine time! We’re talking fabulous abilities of what

computers can do, but computers can be no better than the things that are

fed into them. So again, it is that whole thing of technique!

Just go and know your masters. As Bloch said, “Don’t go to the books!

Don’t go to the books. If you want to study counterpoint go to Palestrina,

go to Orlando. If you want to study harmony, go to Bach. If you

want to study form, go to Mozart and Beethoven. If you want to study

orchestration, go to Wagner, Strauss, Ravel. Books, books, books, books

— so dangerous are the treatises. Schools, schools, schools are so

problematic.” But you’ve got to study and experience the voluptuous

joy of finding out the secrets of Mr. Bach and Ravel! My God, what

wonderful secrets are there! The more tools and the more skills you

have, but computers are labor-saving only if you’ve done the labor to put

into them.

RC: If you have any thought that you might like

to do anything else, then by all means do something else. Composing

doesn’t get easier. The technical thing of being able to put notes down

on paper and knowing the ranges and instrumental difficulties and things like

that finally become second nature. Those things become easier.

Taste and choice, those very difficult things to even define become harder

and harder. Then there is the tyranny of that blank paper! There

are some mornings I just don’t want to do that three hours. I promise

you that I just don’t! But I do, and I really sit there. Being

an objective person, I don’t really like to waste time, and so the little

old mind starts working and something comes out. If nothing else, I’ve

got parts to copy, and nothing is more tedious that that. I’d rather

compose than copy parts. Oh golly, what advice? Just study!

Just know as much as you possibly can! The more tools one has — and

we’re in a position now that the tools are becoming available! I’m not

just talking of twelve-tones and aleotoric and repetition and minimalism.

We’re talking machine time! We’re talking fabulous abilities of what

computers can do, but computers can be no better than the things that are

fed into them. So again, it is that whole thing of technique!

Just go and know your masters. As Bloch said, “Don’t go to the books!

Don’t go to the books. If you want to study counterpoint go to Palestrina,

go to Orlando. If you want to study harmony, go to Bach. If you

want to study form, go to Mozart and Beethoven. If you want to study

orchestration, go to Wagner, Strauss, Ravel. Books, books, books, books

— so dangerous are the treatises. Schools, schools, schools are so

problematic.” But you’ve got to study and experience the voluptuous

joy of finding out the secrets of Mr. Bach and Ravel! My God, what

wonderful secrets are there! The more tools and the more skills you

have, but computers are labor-saving only if you’ve done the labor to put

into them.

Arts

Week hosts Richard Cumming, composer

Richard Cumming was born in Shanghai, raised in the Philippines and schooled

in the American West under such teachers as Rudolf Firkusny and Lili Kraus.

for piano, and Ernest Bloch, Arnold Schoenberg and Roger Sessions in composition.

He has toured 49 of the 50 United States. Canada. Europe and the Far East

as solo pianist. Assistant Conductor for the Santa Fe Opera, and accompanist

for such artists as Helen Vanni, Phyllis Curtin, Donald Gramm. Florence Kopleff,

Mildred Miller. Anna Russell, Martial Singher and Jennie Tourel. He has taught

at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, the University of Saskatchewan

and the Rhode Island Governor's School for Youth in the Arts for which he

has also served as Director in 1970.

Richard Cumming was born in Shanghai, raised in the Philippines and schooled

in the American West under such teachers as Rudolf Firkusny and Lili Kraus.

for piano, and Ernest Bloch, Arnold Schoenberg and Roger Sessions in composition.

He has toured 49 of the 50 United States. Canada. Europe and the Far East

as solo pianist. Assistant Conductor for the Santa Fe Opera, and accompanist

for such artists as Helen Vanni, Phyllis Curtin, Donald Gramm. Florence Kopleff,

Mildred Miller. Anna Russell, Martial Singher and Jennie Tourel. He has taught

at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, the University of Saskatchewan

and the Rhode Island Governor's School for Youth in the Arts for which he

has also served as Director in 1970.His compositions, published by J.&W. Chester in London and Boosey and Hawkes in New York, have been performed throughout the world by John Browning, Rudolf Firkusny, Donald Gramm, Cornell MacNeil, Helen Vanni, the New York Philharmonic, amongst others, and have gained him awards from the National Federation of Music Clubs, ASCAP, the Ford and Wurlitzer Foundations. He has composed the music to over 50 plays for such theatres as the Phoenix Theatre in New York, the Milwaukee Repertory Theatre. ESSO Repertory Theatre on nationwide TV. California's Marin Shakespeare Festival, Princeton's McCarter Theatre, the Loretto Hilton Center in St. Louis and the Trinity Square Repertory Company in Providence, Rhode Island, where he is currently in his sixth season as Composer-in-Residence and Director of Project Discovery. Since the first of this year, he has been traveling in the United States as a Consultant for the National Endowment for the Arts and the recording of his 24 Preludes for Piano has been released on DESTO Records as performed by the brilliant young American pianist, John Browning. [CD re-issue is shown farther up on this webpage.] |

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at my home in Chicago on September

26, 1988. Portions were broadcast (along with recordings) on WNIB in

1993 and 1998. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this

website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.