|

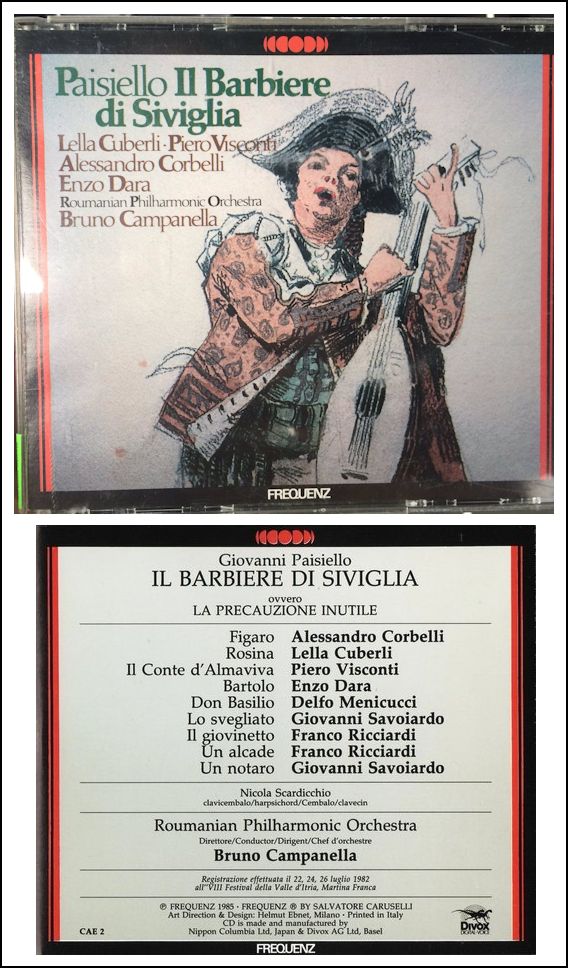

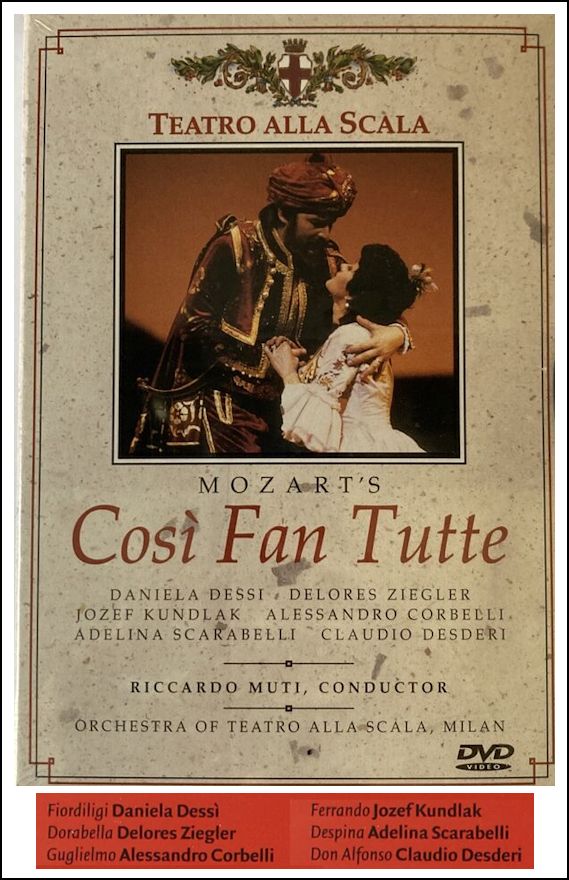

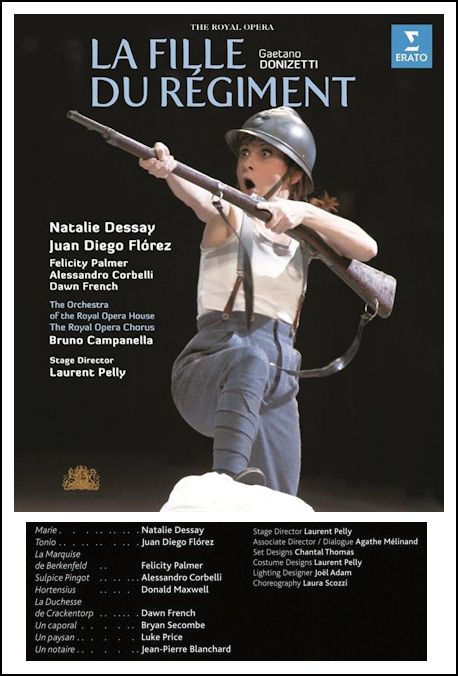

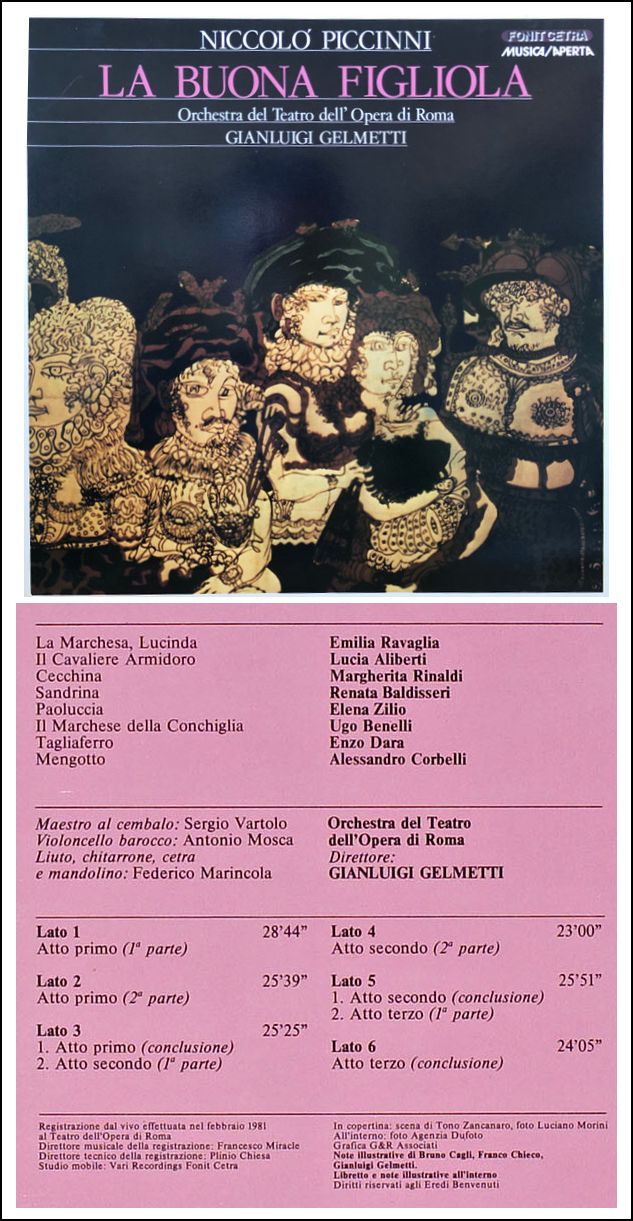

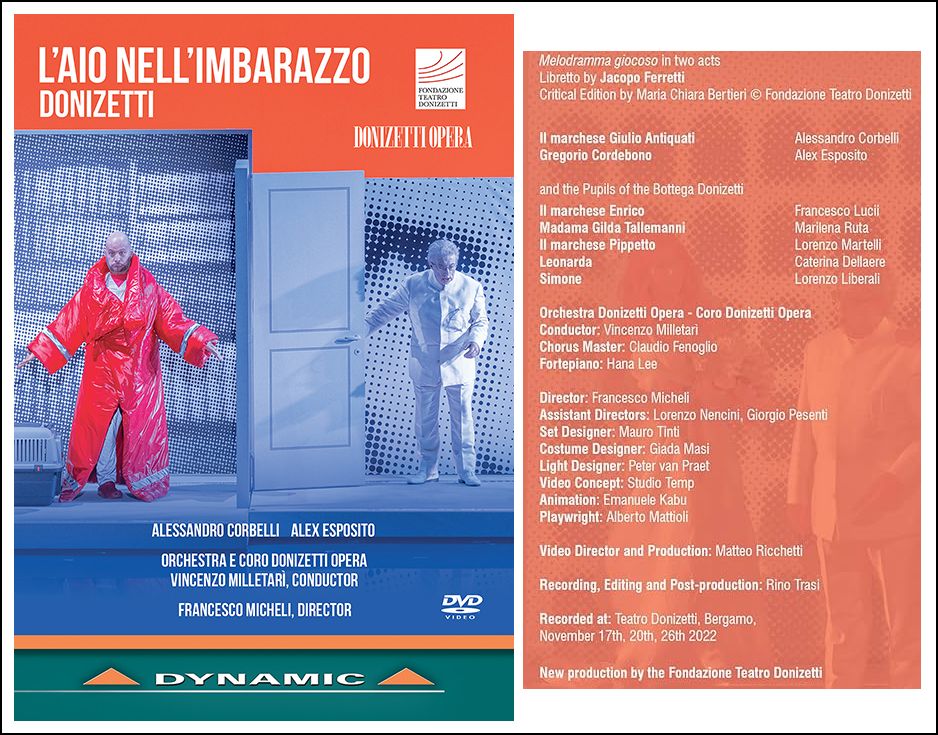

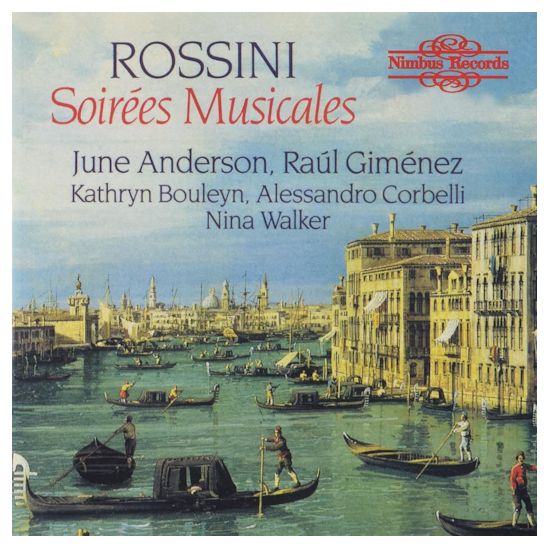

Alessandro Corbelli (born September 21, 1952) is an Italian baritone. One of the world's pre-eminent singers specializing in Mozart and Rossini, Corbelli has sung in many major opera houses around the world, and has won admiration for his elegant singing style and sharp characterizations, especially in comic roles. Corbelli was born in Turin, Italy and studied with Giuseppe Valdengo and Claude Thiolas. He made his debut in 1973 in Aosta, Italy as Monterone in Verdi's Rigoletto. Subsequently, he appeared at La Scala in Milan singing in all three of the Mozart/Da Ponte operas under conductor Riccardo Muti, and also in such cities as Turin, Verona, Bologna, Florence, and Naples, as well as major opera houses in Switzerland, France, Austria, Germany, England, Spain, Israel, and North and South America.At the beginning of his career Corbelli sang lyric baritone roles, but his natural talent for comedy caused him eventually to be typecast in comic parts. Among the buffo roles he has performed and/or recorded are Dr. Bartolo in Rossini's Il barbiere di Siviglia, Taddeo in Rossini's L'italiana in Algeri, Don Geronio in Rossini's Il turco in Italia, Dulcamara in Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore, and the title role of Donizetti's Don Pasquale. He has frequently shown his versatility by singing two roles from the same opera, such as Figaro and the Count in Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro, Leporello and the title role in Don Giovanni, Guglielmo and Don Alfonso in Così fan tutte, and Dandini and Don Magnifico in Rossini's La Cenerentola, among others. Although primarily associated with Italian-language comic roles, Corbelli's résumé shows his wide-ranging interests and versatility, including French and German roles such as Sulpice in Donizetti's La fille du regiment, and Papageno in Mozart's Die Zauberflöte, Baroque opera including Seneca in Monteverdi’s L'incoronazione di Poppea, and a twentieth-century English-language opera, Nick Shadow in Stravinsky’s The Rake's Progress. He has also sung roles in later Italian comic operas, including the title roles in Verdi's Falstaff and Puccini's Gianni Schicchi. He is active in the concert hall as well, performing as a soloist in oratorios and vocal symphonies. |

Alessandro Corbelli with Lyric Opera of Chicago

1986-87 La bohème (Marcello) with Ricciarelli/Daniels, Daniels/Brown, Polozov/Shicoff/Araiza, Washington, Capecchi; Tilson Thomas, Copley, Pizzi 1988-89 Falstaff (Ford) with Wixell, Daniels, Sandra Walker, Horne, Hadley, Swenson, Andreolli; Conlon, Ponnelle 1991-92 L'elisir d'amore (Belcore) with Gasdia, Hadley, Desderi, Futral (Giannetta); Pappano, Chazallettes 2005-06 Cenerentola (Magnifico) with Kasarova, Flórez, Hernandez, Doss, Curnow, Arwady; Campanella, Ponnelle/Asagaroff 2009-10 L'elisir d'amore (Dulcamara) with Cabell/Phillips, Filianoti/Lopardo, Viviani; Campanella, Chazalettes/Liotta 2013-14 Barber of Seville (Bartolo) with Gunn, Leonard, Shrader, Ketelsen, Cantin; Mariotti, Ashford, Pask 2015-16 Cenerentola (Magnifico) with Leonard, Brownlee, Priante, Van Horne, Newman, Rosen; Davis, Font 2017-18 Così fan tutte (Alfonso) with Martínez, Crebassa, Stensen, Hopkins, Tsallagova; Gaffigan, Cox/Ravella, Perdizolla 2019-20 Barber of Seville (Bartolo) with Crebassa, Brownlee, Baczyk, Edge; Davis, Ashford/Faircloth, Pask 2023-24 Fille du régiment (Sulpice) with Oropesa, Brownlee, Miller, Hermalyn; Scarapucci, Pelly/Räth.Thomas Cenerentola (Magnifico) with Berzhanskaya, Swanson, Hopkins, Newton, Castillo, Maekawa; Lin, Ponnelle/Fortner |

|

Henry Kenneth Alfred Russell (3 July 1927 – 27 November 2011) was a British film director, known for his pioneering work in television and film, and for his flamboyant and controversial style. His films were mainly liberal adaptations of existing texts, or biographies, notably of composers of the Romantic era. Russell began directing for the BBC, where he made creative adaptations of composers' lives which were unusual for the time. He also directed many feature films independently and for studios.

No Ken Russell opera is complete without Nazis, and of course the production of La bohème was controversial. Cecilia Gasdia sang Mimì, and Elena Zilio was Musetta. The great-grandson of the composer threatened legal action, as had the great-grandson of Richard Strauss when Russell did Salome. Five years after Russell filmed the Oscar Wilde play, he returns and directs Richard Strauss' opera of the same work. OPERA magazine (October 1993) said of the Bonn production, "The first-night audience did not enjoy the new work. Ken Russell returned thanks for their demonstration of displeasure in his own fashion, by bowing with his behind towards the audience". The singers were Emily Rawlins (Salome), Graham Clark (Herod), Helga Deresch (Herodias), David Pittman-Jennings (Jokanaan), and Marcus Haddock (Narraboth). Dennis Russell Davies conducted the Beethovenhalle Orchestra. The great-grandson of Strauss also threatened legal action. Moving to Madama Butterfly, R John Gruen wrote in The New York Times

on May 22,1983: "There is nothing predictable about Mr. Russell's

handling of Madama Butterfly. While he is hardly the first director

to tamper outrageously with an operatic masterpiece, his treatment

of Puccini's opera is certain to produce some critical and public fireworks.

For one, he has updated Butterfly to World War II, just prior

to Pearl Harbor. For another, he has turned Cio-Cio San into a prostitute

working in the red-light district of Nagasaki. Goro has become her

pimp, while Lieutenant Pinkerton is a callous American opportunist.

The opera ends with an elaborate simulation of the atom bomb falling

on Nagasaki. |

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 15, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1991, 1997, and 1998. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks for Marina Vecci, Production Administrator with Lyric Opera for providing the translation. Also, my thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.