|

Early automotive events of

specific

interest - a chronology

1892

1894 Henry G. Morris and Pedro G. Salom

construct and test a

battery-operated

car 1895 Morris & Salom build 4 Electrobats, as they call their new car. Pope

Manufacturing Co., Hartford, CT,

manufacturers

of the Columbia bicycle, 1896 Morris & Salom form the Electric

Carriage & Wagon Co.,

concentrating on A.L. Riker forms the Riker Electric

Motor Co. in Brooklyn, NY.

(One

of the first 1897 Isaac L. Rice,

president of Electric

Storage

Battery Co, and the Electric Boat Co., May -

Production begins on the Columbia

Electric

by the Pope Manufacturing Co. The vehicles 1899 The automobile division of Pope Manufacturing Co. becomes the Columbia Automobile Co.. The Riker

Electric Motor Co. is taken over

by

Electric Vehicle Co. Production of the Riker car Dodge brothers work for

Canadian Typothetac Company in Windsor,

Ontario.

Organize the 1900 The Columbia

gasoline

car goes into production, with the engine in front instead of under the

Columbia

Automobile

and

the Electric Vehicle Co. merge to form the Columbia & Electric

Carl Breer builds his first car - a steam car. Evans & Dodge Bicycle Co. taken

over by

National Cycle & Automobile Company, April 17 - James Churchill Zeder

born, Bay

City, MI (youngest brother of Fred M. Zeder). 1901 Columbia &

Electric

Vehicle, renamed the Electric Vehicle Company, acquires the Selden

Dodge brothers move to Detroit, MI

and open

a shop on Beaubien Street making bicycles The Graham brothers, Joseph C.,

Robert C.

and

Ray A, begin a glass-manufacturing Waltern P. Chrysler marries Della

Forker

and

is promoted to foreman at Salt Lake City. 1902 Jonathon Dixon Maxwell, of Detroit,

MI,

joins

with Charles B. King and W.T. Barbour to Dodge brothers get contract to build 3,000 transmissions for Olds Motor Works. Frederick J. Haynes accepts job as manager of H.H.Franklin Company, Syracuse, NY. Walter P. Chrysler accepts job as

manager of the

Colorado and Southern shops in Trinidad, CO. 1903 J.D.Maxwell leaves Northern and goes

to

work

for the Briscoe brothers, Detroit sheet metal The Electric

Vehicle

Company joins with nine other car manufacturers to form the Licensed

The

National

Association

of Automobile Manufacturers conducts an Endurance Test Albert A. Pope

withdraws

from the Electric Vehicle Company, and

begins

production of the Dodge brothers equip their plant to

build

engines

for Ford in return for 10% interest in Ford 1904

The Pope company sets up the Pope-Tribune car in Hagerstown, MD, and the

The Mud Larks hold a Reunion Dinner at Madison Square Garden, during the Auto Show. Three

other firms are formed this year, all independent of each other as well

as the Columbia The Alden Sampson company had a

contract to

build the Moyea chassis and running gear for After a

rival set

of drivers from another firm make a new time of 72 hours 46 minutes,

The Stoddard-Dayton car is built by

John

Stoddard,

son of Henry Stoddard, a Dayton paint 1905 Alden Sampson takes over the

Consolidated

Motor

Co. The Moyea becomes the Sampson. The Maxwell-Briscoe in production with shaft drive instead of the usual chain drive. Roy D. Chapin and Howard E. Coffin,

leave

their

jobs as engineers with Oldsmobile, and with Walter P. Chrysler becomes division chief for of the Fort Worth and Denver City Railroad. Owen R. Skelton becomes engineer for

Pope-Toledo

Company. 1907 Frank Briscoe (one of the Briscoe

brothers)

provides financial backing for a light car designed The Columbia four introduces dual carburetors. The economic

recession

of the year brings about the downfall of the Pope empire. The Overland

Owen R. Skelton becomes transmission specialist for Packard Motor Car Company. Walter P. Chrysler becomes

superintendent

of

the shops of the Chicago & Great Western 1908 Talks between the Briscoe brothers

and

William

C. Durant to form one big automobile Columbia

introduces

Model

XLVI, a 4-cylinder gasoline engined vehicle that drove an With sales sliding at Thomas-Detroit,

Hugh

Chalmers is brought on board from National Cash Walter P. Chrysler attends the Chicago Auto Show and purchases a Locomobile. David A. Wallace becomes a machinist

at

Buick

Motor Company. 1909 The Electric Vehicle Company becomes the Columbia Motor Car Co. Howard E. Coffin and Roy D. Chapin

design a

new lighter car and leave Chalmers-Detroit to February 24 - Hudson Motor Car

Company

formed,

by Roy D. Chapin and Howard E. Stoddard-Dayton forms the Courier Car

Co.,

Dayton, OH, to produce a lower-priced car, Carl Breer and Fred M. Zeder employed with Allis-Chalmers. Walter P. Chrysler becomes work

superintendent

of the American Locomotive Co. Herman L. Weckler joins American

Locomotive,

where he meets Walter P. Chrysler. 1910 The United

States

Motor

Company is formed, taking control of Maxwell-Briscoe Motor Co., Alden Sampson was run basically as a

hobby,

the owner not caring if profits were produced Dodge brothers build a new plant in Hamtramck, MI Hugh Chalmers, E.R.Thomas and Roy D.

Chapin

groups dispose of their holdings in the others The Chalmers-Detroit dropped "Detroit" . Now known as Chalmers. Hudson Motor Car Company builds its

new

assembly

plant in the Pointe Claire area of K.T.Keller becomes chief inspector at

Maxwell-Briscoe

plant in Tarrytown, NY. 1911 Production of the Alden Sampson

company

moved

to Detroit. Truck production continues 1912 Columbia produces a sleeve-valved model, the Columbia-Knight, with 410-cid Knight engine Stoddard introduces a 525-cid sleeve-valved Stoddard-Knight Benjamin Briscoe leaves United States Motor Co. and forms Briscoe Motor Co., Jackson, MI September 12 - the United States Motor Company in receivership Walter P. Chrysler hired by Charles W. Nash, president of Buick Motor Company, as works manager in Flint, MI at annual salary of $6,000. Chrysler helped to raise production from 20 cars a day to 550. K.T. Keller leaves Maxwell-briscoe to become the general superintendant of Northway Motors, a subsidiary of General Motors Company Frederick J. Haynes leaves H.H. Franklin Company for Dodge Brothers December 31 - the Maxwell-Briscoe company becomes the Standard Motor Company, a Delaware corporation. The company is headed by Walters Flanders (of E.M.F. fame) 1913 The Columbia, Brush, Stoddard and Courier end production January 25 - The Standard Motor Company becomes the Maxwell Motor Company *

* *

* *

* *

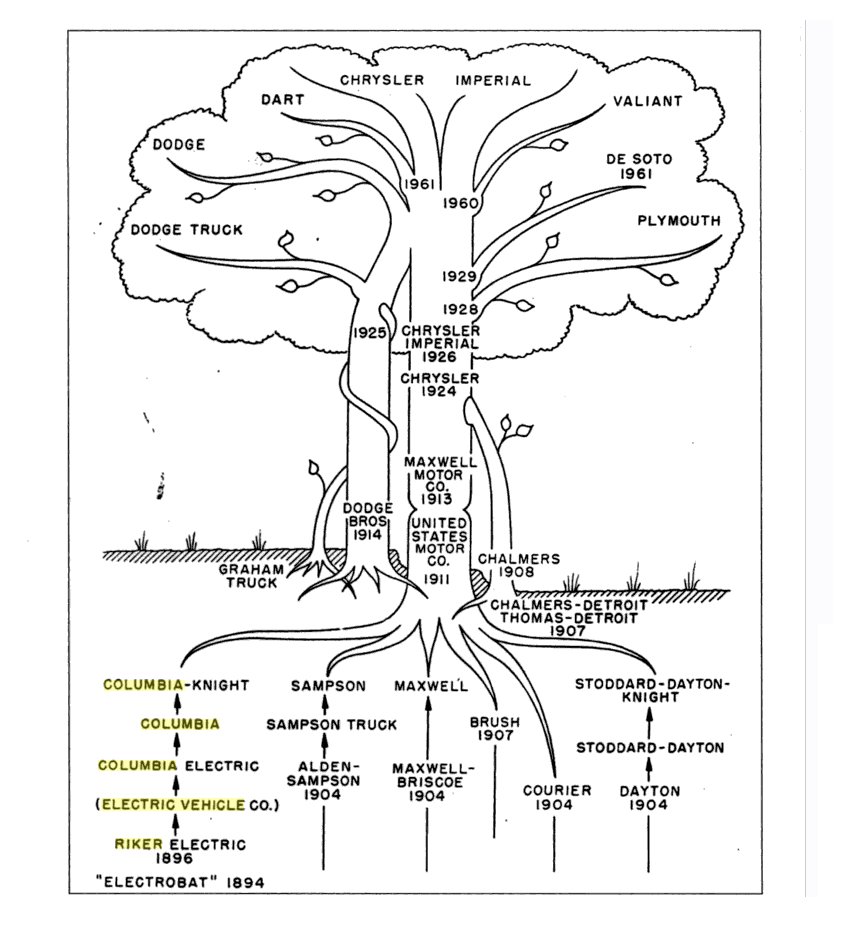

One of the main roots of the

Chrysler Corporation is  |

Below is a section from a much longer presentation.

The idea that the Electric Vehicle Company was a failure

is only correct in light of the larger overall picture.

However, in its day the company was very successful,

and a played a major role in the development of the

automobile in this country and around the world!

|

The Electric Car and the Burden of History: David A. Kirsch Reprinted from Business and Economic

History, Volume Twenty-six, no. 2, Winter 1997. Copyright

©1997 by the Business History Conference. ISSN 0894-6825.

The Failure of the Electric Vehicle Company, 1897-1901 In the spring of 1897, the Electric Carriage & Wagon Company established the first motor vehicle service in the United States. Using approximately a dozen vehicles, the EC&WC's electric taxicabs were intended to compete with the horse-drawn cabs then in service on the streets of New York City. A central claim of the dissertation is that this venture-and its many progeny-represented a legitimate alternative technological system to that embodied by the choice of internal combustion. How did the vision of motorized road transportation put forward by engineers Henry Morris and Pedro Salom differ from that shared by the other automobile manufacturers of the day? Among the several distinguishing features of Morris and Salom's effort, the most important was their decision to retain ownership of the experimental motor vehicles. Morris and Salom were convinced that the motor car-regardless of its motive power-was as yet too complicated and unreliable to be entrusted into the hands of lay operators. Recognizing the latent demand for motor service, Morris and Salom opted to create a transportation service company rather than a simple automobile sales company. In this respect, the two pioneers differed not only from the typical internal combustion vehicle producers, but also from other electric vehicle manufacturers as well. Morris and Salom's strategy was based upon the model of livery stables that leased horses and carriages by the trip, by the day, or even by the month. They chose not to sell artifacts into the hands of unsuspecting and untrained owners, but instead to design an integrated transportation system. Their initial operating results, self-reported in the automotive press after six months of service, suggested that their vehicle service was not yet competitive with the horse-drawn cabs. Daily mileage averaged approximately 11 miles per cab, and using cost estimates from studies conducted at MIT in the early 1910s, the electric vehicle service was almost certainly a money loser during its first half-year. Yet, regardless of its initial profitability, the venture established an alternative to horse-drawn passenger transportation service and demonstrated sufficient potential to encourage the owners to expand the fleet from a dozen to over 100 electric vehicles. Over the course of the following four years, the electric vehicle service started by Morris and Salom blossomed into the largest automobile enterprise of the day. At its height the Electric Vehicle Company was both the largest vehicle manufacturer and the largest owner and operator of motor vehicles in the United States. With multiple assembly plants, operating companies in the half-dozen largest cities in the country, and sales agents from San Francisco to Mexico City to Paris, the EVC was also one of the first American motor vehicle makers to move away-however tentatively-from the small-scale production of custom-made vehicles that dominated the emerging industry in the 1890s. Rather, the expansive, multi-divisional corporate structure of the EVC anticipated some of the innovations in corporate governance-Alfred Chandler's managerial revolution-which would spread through the rest of the automobile industry in the decade following the collapse of the EVC. Unfortunately, following its takeover by the Whitney-Philadelphia syndicate, the Electric Vehicle Company also became synonymous with trust building, stock jobbing, financial chicanery, and the infamous Selden patent. Had the EVC succeeded in establishing profitable operating companies in major urban areas, and had those companies attracted customers, suppliers, and infrastructure providers to the electric vehicle bandwagon, it is possible to envision a radically different transportation system today. As it was, the enterprise was beset by problems, from production delays and warehouse fires to shareholder suits and blistering public attacks. Although several regional operating companies were established and perhaps 2,000 vehicles distributed to them, by 1902 all had declared bankruptcy, and the parent company was reduced to little more than a holding company for the contested Selden patent. The assets of the New York branch were transferred to a local operator, and the vehicles were used intermittently for service in and around Central Park for several more years. An unfavorable legal decision and an economic downturn would ultimately force even the EVC itself into default in December, 1907, ending once and for all the founders' dreams of electric cabs on every corner in every major American city. Between its humble beginnings and its ignominious collapse, the EVC demonstrated that electric vehicles could provide valuable transport service. |