|

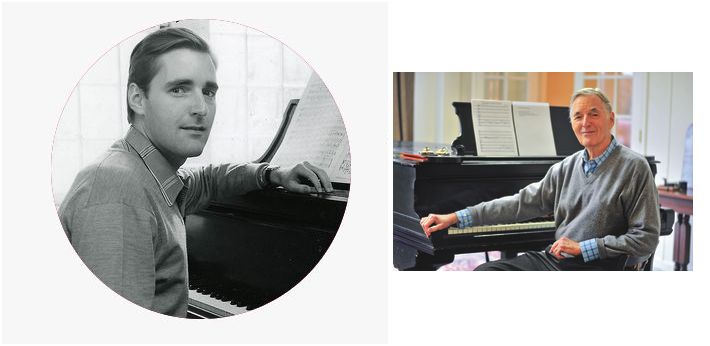

Kenton Coe began his musical training at the Cadek Conservatory in Chattanooga and continued studies in Knoxville before attending Sewanee Academy. He attended Hobart College in upstate New York for two years before entering Yale University, from which he graduated as a History of Music major. He studied composition at Yale with Paul Hindemith and Quincy Porter. He worked privately for three years in Paris with Nadia Boulanger both at the Paris Conservatory and the Fontainebleau School, and received two French Government scholarships at her request. Sponsored by Aaron Copland, Kenton Coe received two fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, where he began his first full-length opera, South, which was premiered in 1965 by the Opera of Marseilles under the direction of conductor Jean-Pierre Marty. A new production of South was given by the Paris Opera with an opening night Gala in the presence of President and Madame Georges Pompidou. A studio recording by the French Radio of this opera was given as a part of their American Bi-Centennial celebration. He has written a one-act comedy, Le Grand Siècle, on a text of Eugène Ionesco, which was premiered by the Opera of Nantes and later recorded for broadcast by the French Radio. Kenton Coe has sketched a second full-length opera, The White Devil, based on the Jacobean play by John Webster and is collaborating with Allen Cargile on a chamber opera based on James Agee's The Morning Watch. In 1989, the Knoxville Opera Company gave, in both Knoxville and Nashville, the highly successful world premiere performances of his third opera, Rachel, based on the tragic love story of Andrew and Rachel Jackson. The libretto was created by fellow-Tennessean and Emmy-Award-winning TV writer, Anne Howard Bailey. == The biography (above) is from the website of the

Bay Area Rainbow Symphony (2013)

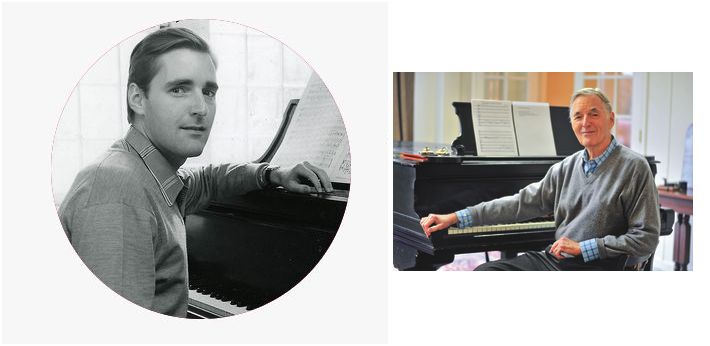

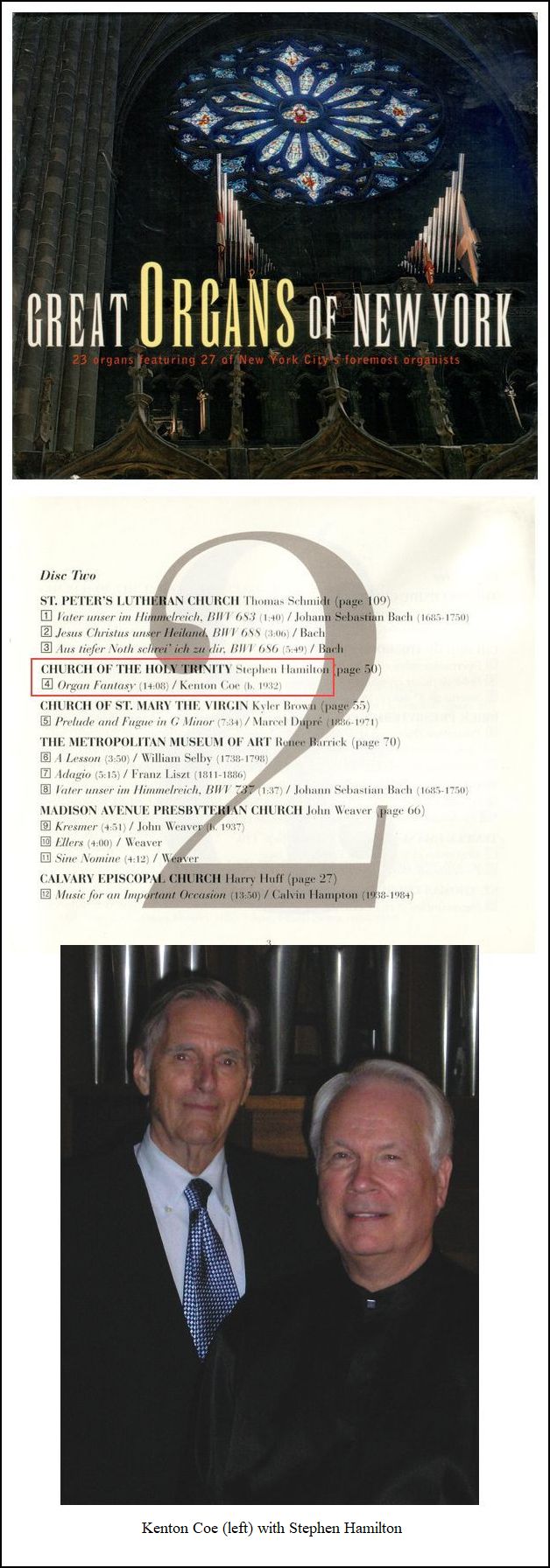

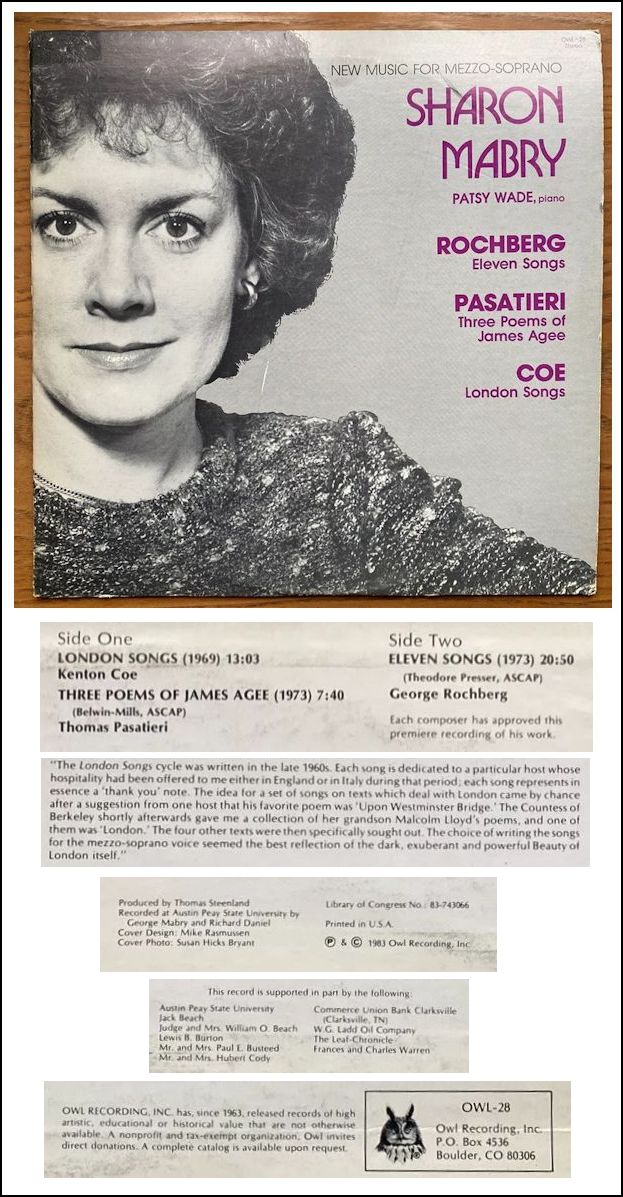

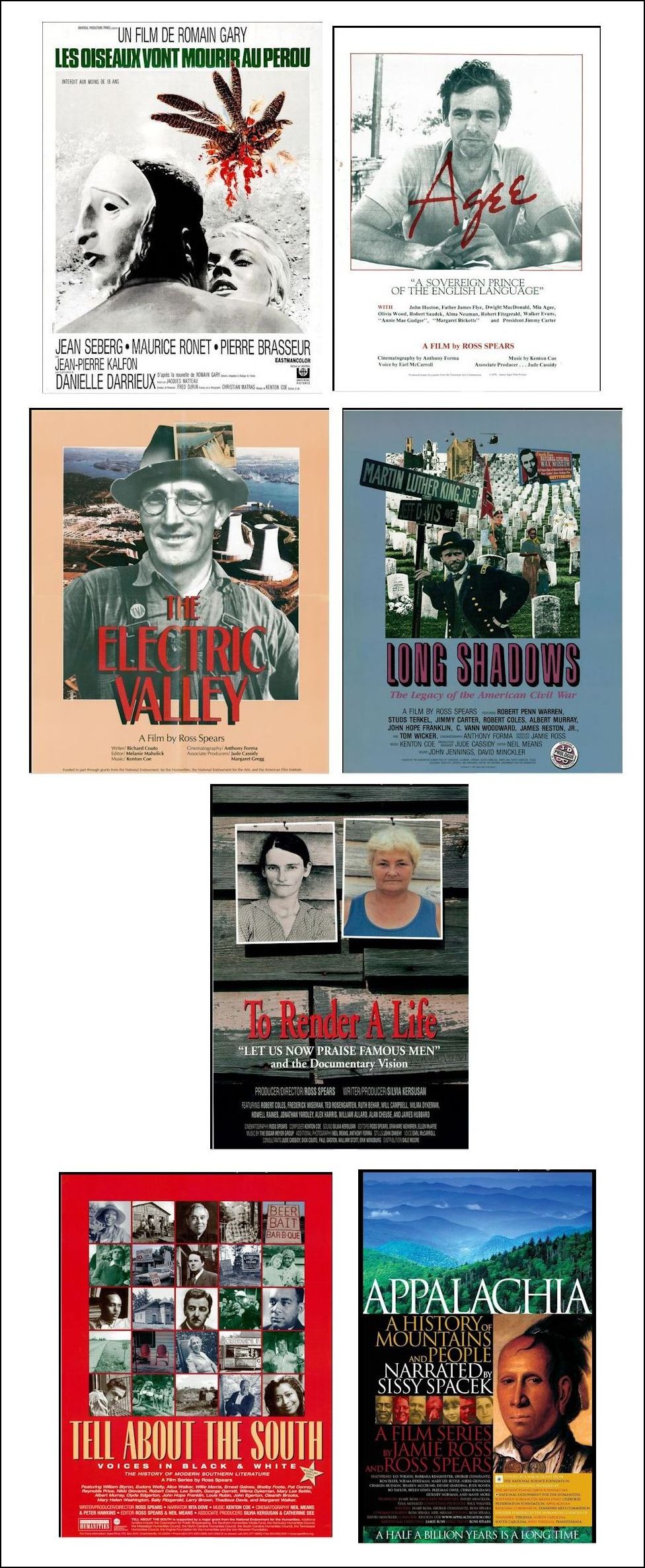

It was during this time that Coe first met Jean-Pierre Marty, a pianist and conductor with whom Coe would share a romantic partnership for most of his life. Coe remained in France until 1957, when he and Marty moved to New York City, where they would remain until Coe returned to Johnson City in 1974 and Marty moved back to France. Aside from a five-year period living in Lake Summit, NC (2007-2012), Coe would stay in Johnson City for the next 43 years, until 2017. He spent his final years in Easley, SC and Asheville, NC, where he died on December 29, 2021. While Coe’s student compositions date to the 1940s, he considered his first mature piece to be the opera “South,” which he began composing in 1960 and worked on until its premiere in 1965 by the Opera of Marseilles, under the direction of Marty. The work, based on Julien Green’s three-act play “Sud” from 1953, would be performed again in 1972 by the Paris Opera, making Coe the first American to have an opera produced by the organization. Coe went on to write a number of stage works (operas, one-act musical plays, and ballets), including the opera “Rachel” on which he collaborated with librettist Anne Howard Bailey and which was premiered by the Knoxville Opera Company in 1989. Coe wrote extensively for piano and organ, including “Sonata for Piano” which was given its American premiere by Kenneth Huber at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. in 1977, and “Fantasy for Organ” (1991) which was commissioned by Stephen Hamilton and served as the focus of Hamilton’s 1992 DMA Thesis. He composed orchestral pieces, works for various chamber ensembles, and various pieces for chorus and vocal soloists. As an active member of the Episcopal Church, Coe also composed numerous anthems and other sacred pieces. Coe also composed over a half dozen film scores, first working with Romain Gary on “Birds in Peru” in 1968, and going on to collaborate with documentarian Ross Spears on a number of films from the late 1970s through the 2010s, including "Agee" (1980) which was nominated for an Academy Award for best feature documentary. Many of Coe’s pieces were written in response to specific commissions, including “Concerto for Organ, Strings, and Percussion” commissioned by the Festival du Commings in 1980; “Scherzo for Clarinet, Brass, and Strings” by the Johnson City Symphony in 1986; “Ischiana” by the Baton Rouge Symphony in 1989; “Purcellular” by the City of London in 1995; and “Architects of Heaven” by the Carolina Concert Choir in Hendersonville, NC around 2008, which Coe once described as “probably the best work I have ever written.” Coe’s work was also supported by various grants, awards, and fellowships throughout the years. This included two ten-week fellowships in 1960 and 1963 from the MacDowell Colony, an artists’ residency and workshop in Peterborough, NH, where he worked on the opera “South” under the sponsorship of composer Aaron Copland; a $75,000 award from the Lyndhurst Foundation in 1985; and various grants from state and federal arts organizations including the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Tennessee Arts Commission. Coe received a number of awards and accolades throughout his life, including the Samuel Doak Award from Tusculum College in 1980, a Governor’s Award in the Arts from the state of Tennessee in 1990, Composer of the Year from the Tennessee Music Teachers’ Association in 1998, and an honorary doctorate degree from East Tennessee State University in 2007. |

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on September 28, 1995. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.