David DeBoor Canfield (b. 23 September 1950, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.) is an American composer and entrepreneur.

Canfield's mother, June DeBoor Canfield, was a former violinist in the Columbus Philharmonic under Izler Solomon, and his father, Dr. John Canfield, had founded the Fort Lauderdale Symphony Orchestra (now the Florida Philharmonic) just before the younger Canfield was born, and was a music educator. It was natural, therefore, that Canfield's earliest musical studies (beginning at age six) in piano, violin, music theory and composition were all with his father, although by the time he had reached high school, these lessons had greatly diminished in frequency due to his father's busy schedule, and Canfield's increasing interest in the subject of chemistry. It was in chemistry, in fact, that he was accepted as a major at Stetson University in 1968, although he received a full scholarship from the school for playing in the University Orchestra, of which he was concertmaster for a year and a half.

Midway through his junior year, Canfield transferred to Covenant

College, where his father was head of the music department, to study music,

and he became the first composition major to graduate from that school.

Taking two years off from his education after graduation, he played violin

professionally in the Fort Lauderdale Symphony, the Miami Opera Association

and the Miami Beach Symphony Orchestra. In 1974, Canfield decided to begin

graduate school and was accepted into Indiana University. His composition

teachers there included John Eaton, Bernhard Heiden and

Frederick Fox. Canfield was awarded the MM in Composition in 1977 and

the DM in Composition in 1983.

Midway through his junior year, Canfield transferred to Covenant

College, where his father was head of the music department, to study music,

and he became the first composition major to graduate from that school.

Taking two years off from his education after graduation, he played violin

professionally in the Fort Lauderdale Symphony, the Miami Opera Association

and the Miami Beach Symphony Orchestra. In 1974, Canfield decided to begin

graduate school and was accepted into Indiana University. His composition

teachers there included John Eaton, Bernhard Heiden and

Frederick Fox. Canfield was awarded the MM in Composition in 1977 and

the DM in Composition in 1983.

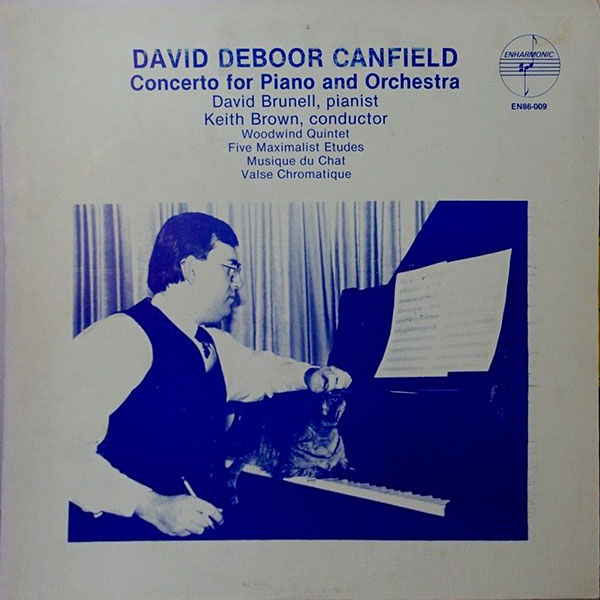

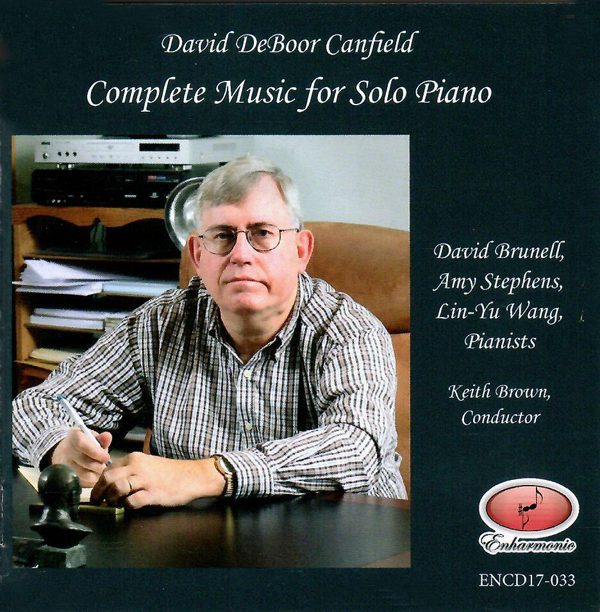

While at Indiana University, his dissertation piece, Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, won the Dean's Composition Competition and was premiered by David Brunell, piano, and Keith Brown, with the Indiana University Orchestra.

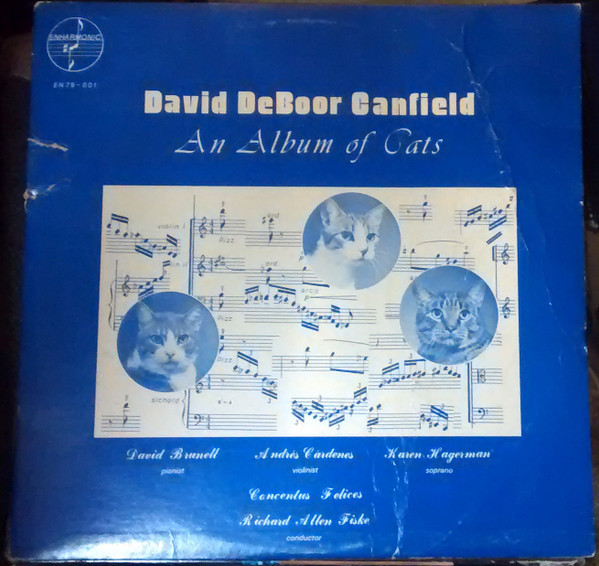

Not interested in pursuing a career as a teacher of composition, Canfield then began Ars Antiqua, which in a short time became the world's largest mail-order business devoted to classical LP records. He also compiled, during the course of running this venture, the world-wide standard price guide for classical records, the latest edition of which contains almost 200,000 different records on all formats. He retired from this business in 2005.

During the 27 years he ran his record business, however, he has continued to compose and receive numerous performances of his works, which include the premiere of his Piano Sonata in Geneva, Switzerland, at the Festival European International in 1990, his Toccata and Fugue in E-Flat Minor in Holland in 1997, and his Overture: The Spirit of Challenger by two different orchestras.

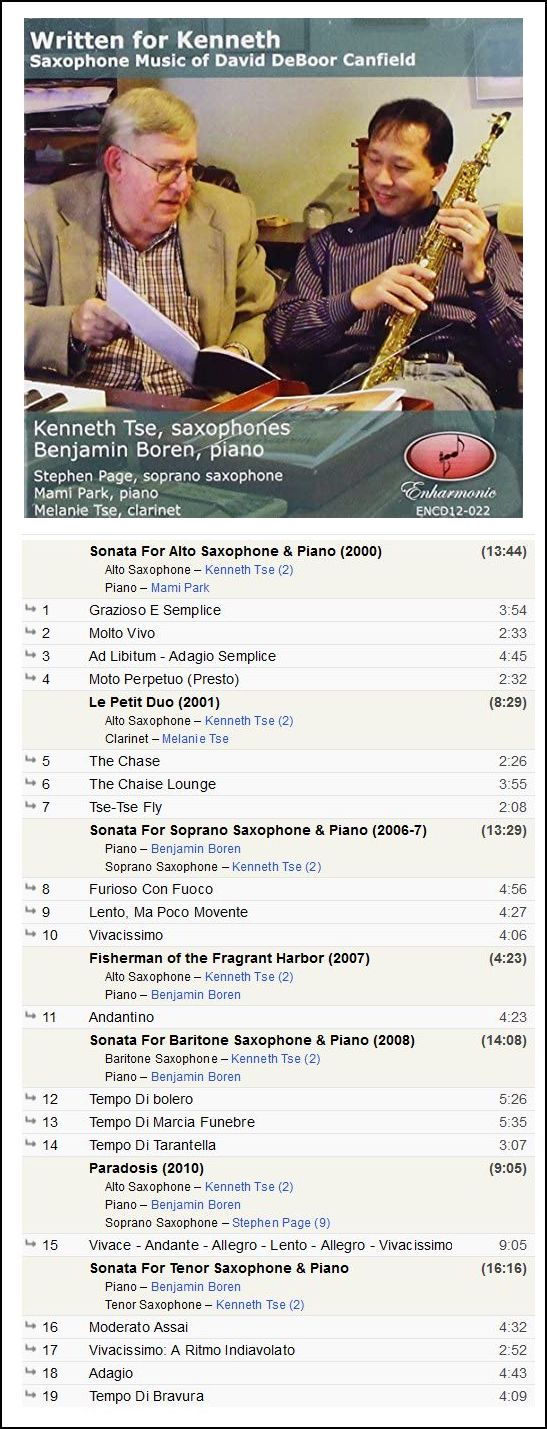

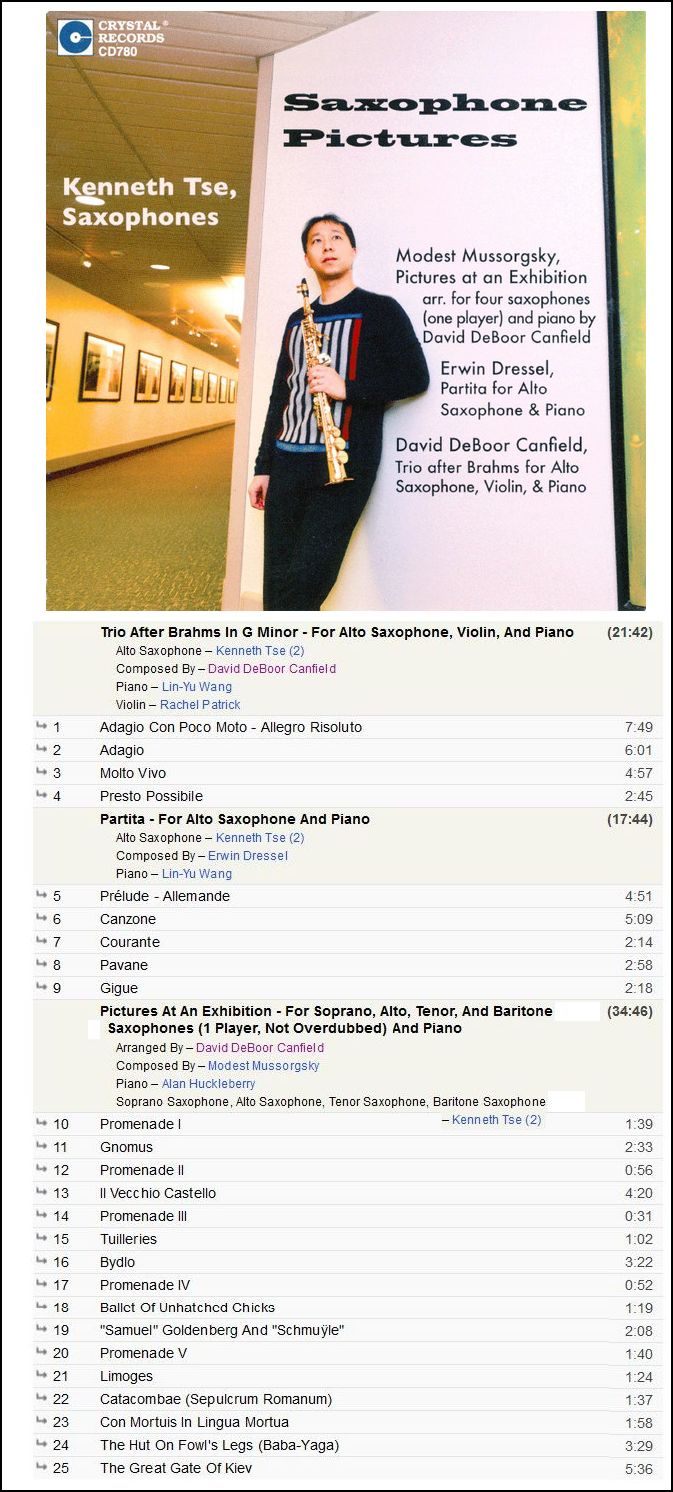

Canfield is the composer-in-residence of the Bloomington Pops Orchestra, which has performed more than a dozen of his pieces. The largest scale of these, the American Patriot Overture, scored for large orchestra, chorus, auxiliary brass and cannons, the Pops performed three times. In 1986, Canfield won the Jill Sackler Cello Composition Contest with his Prisms for Violoncello Quartet and Orchestra of Violoncellos. This work was premiered at the Third American Cello Congress by Laszlo Varga, conductor, and an orchestra comprising some of the world's most distinguished cellists. It was subsequently performed at the Eva Janzer Memorial Concert at Indiana University in October, 2000 under the direction of faculty member, Emilio Colon. In February of 2001, a three-day festival featuring Canfield’s music was presented by the faculty and students of the University of Central Oklahoma at Edmond, OK. A number of works were premiered at this festival, including his Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano, by the dedicatee, Kenneth Tse, who is on the faculty of the University of Iowa. Tse has performed it widely, most recently at the World Saxophone Congress in Minneapolis. Also premiered at this same festival was his Sonata for Trumpet and Piano, performed by James L. Klages, who is on the faculty of the University of Central Oklahoma. In 2003, The Proclamation, a 90-minute oratorio jointly composed with his father was premiered in Bloomington, Indiana to critical and audience acclaim.

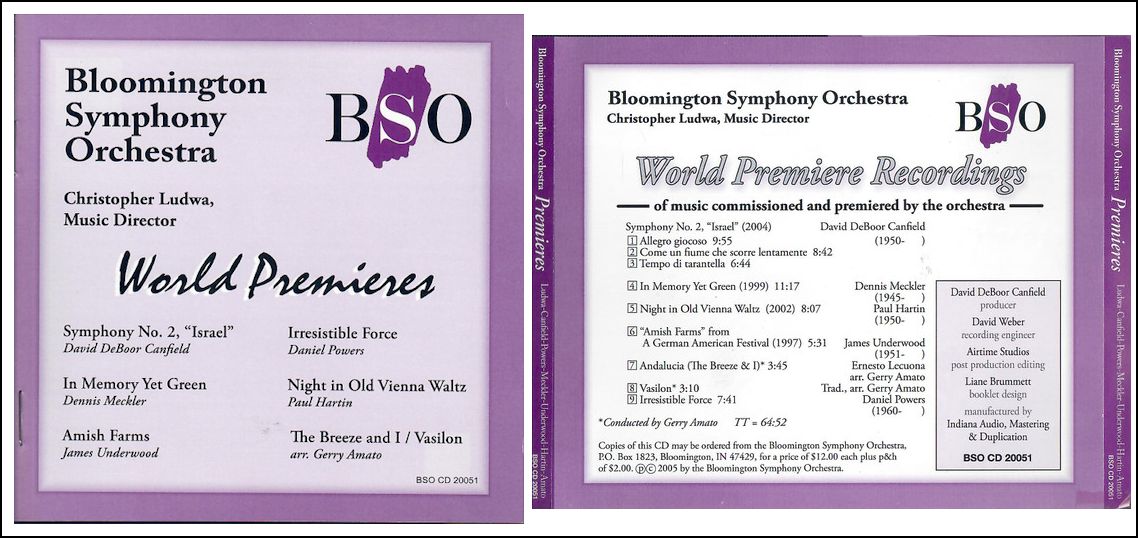

In January, 2005, Canfield’s Symphony No. 2 Israel was premiered by the Bloomington Symphony Orchestra, and his Symphony No. 3, Retrospective, was premiered in 2005 by Stephen Pratt and the Indiana University Symphonic Band.

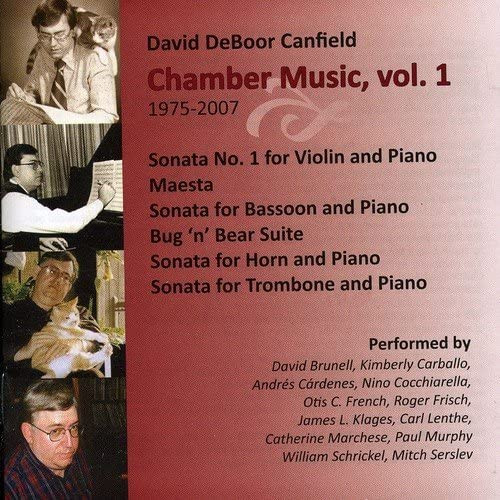

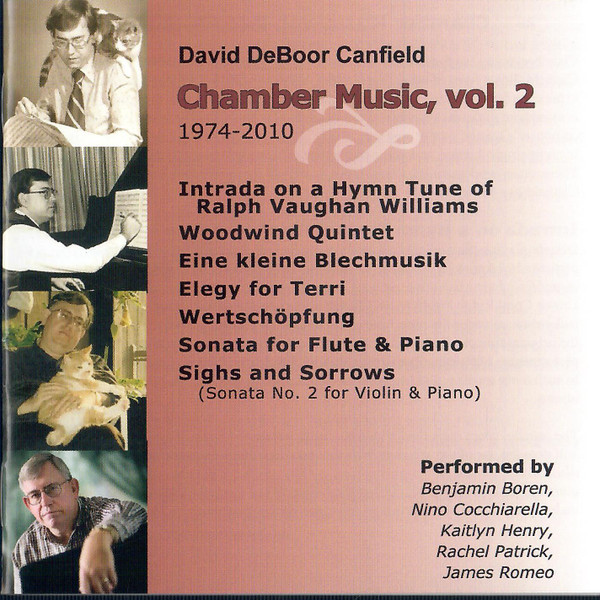

Canfield's list of works includes three symphonies, several works

for solo organ, a string quartet, a string trio, sonatas for trumpet,

piano, bassoon, horn and alto saxophone, two violin sonatas, two concert

overtures and a suite of orchestra pieces for a projected ballet. Also

in his canon are a number of works for brass ensemble, including Oklahoma

Requiem, Intrada on a Hymn Tune of Ralph Vaughan Williams, Microtonal

Fanfare and the Bug 'n' Bear Suite and several solo piano

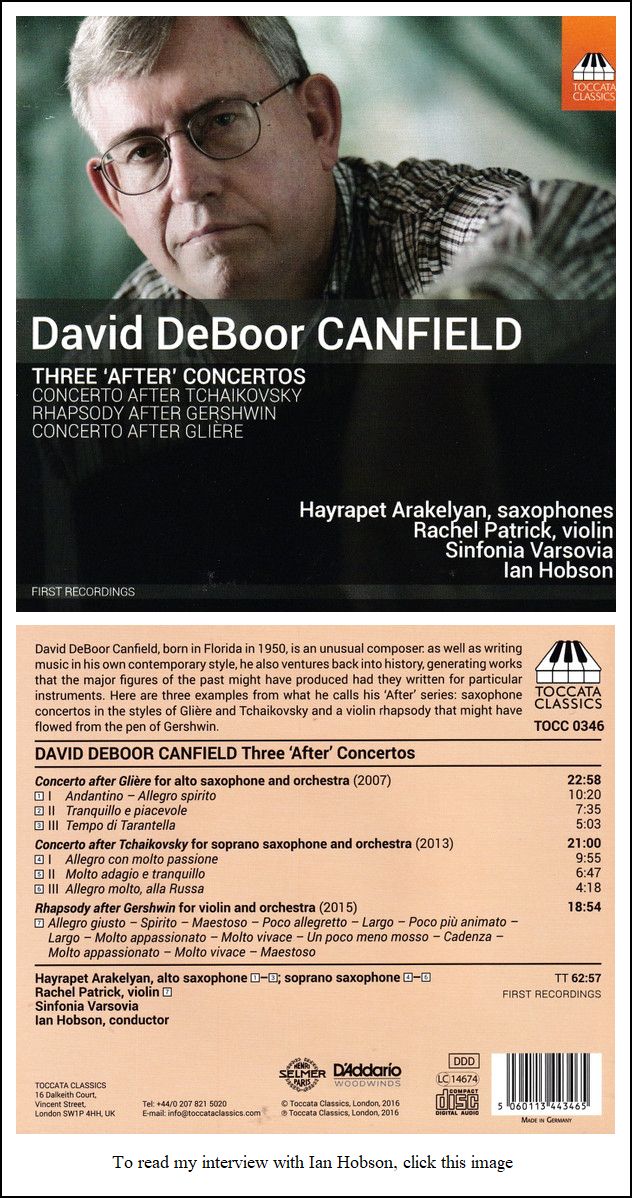

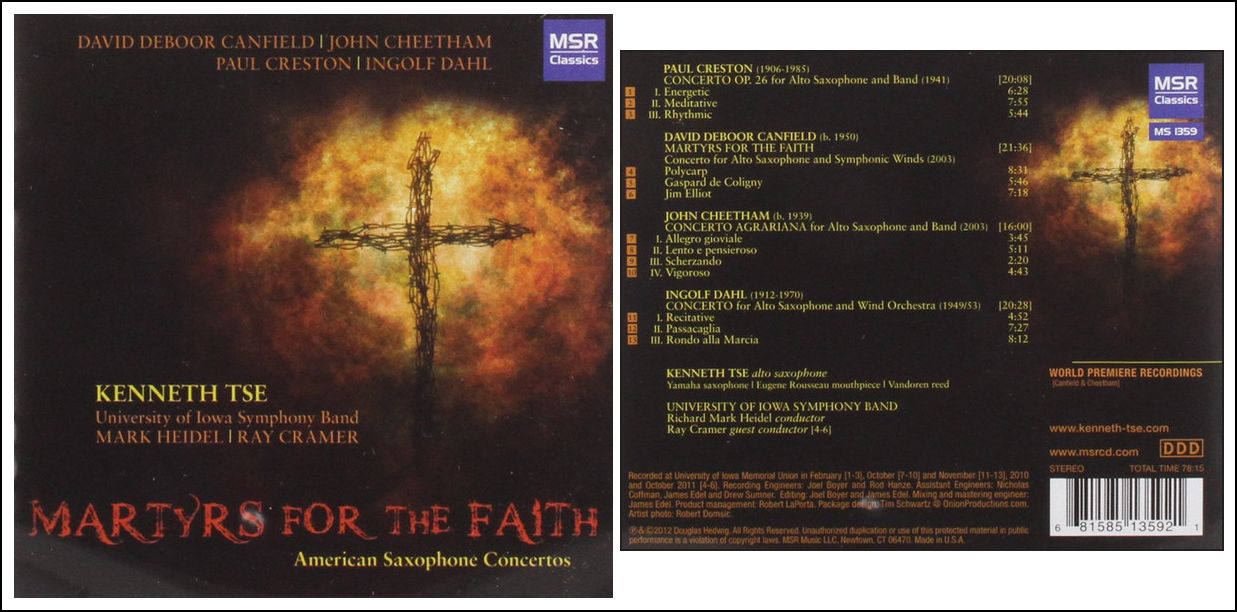

pieces. In July of 2006, his Martyrs for the Faith: Concerto for Alto

Saxophone and Symphonic Winds was a featured work at the World Saxophone

Congress in Ljubljana, Slovenia.