Composer Gordon Binkerd

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

At the end of May of 1988, I had the pleasure of speaking with Gordon

Binkerd on the telephone. He was charming and witty, and thought carefully

about his responses to my questions.

Portions of the interview were used on WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago, and

now I am glad to be able to present the entire conversation.

Bruce Duffie: You spent a number of years

teaching and also composing. How did you balance those two sides

of your career?

Gordon Binkerd: Pretty much by teaching in the

winter, and composing in the summer.

BD: Did you get enough time to compose?

Binkerd: I guess not, but you have to make a

living. But I still got a great deal of music written, so I shouldn’t

complain. The question is if you have unlimited free time, you

tend to waste it, and I made very good use of my summers as far as composition

is concerned.

BD: Did you ever bring anything back with you

in the fall, and continue working on it while you were teaching?

Binkerd: Yes, of course! There are things

that I can do during the winter months. I could copy music, or copy

parts. They will always take a lot of time, but they’re necessary,

and you don’t have to have any need of staying in order to do them.

BD: It’s just the busy work involved?

Binkerd: It’s just something you can do at any

time, without any prolonged planning or need for prolonged free time.

So, that’s where it worked out. I usually would keep something going.

Maybe not large pieces, but small pieces. I used to have a habit of

getting up early in the morning —

maybe three or four o’clock

— and I did that for a number of years.

It got almost to be a habit of mine. I would wake up then and be

ready to go, but I don’t anymore. [Laughs] There’s no need

to anymore because I have retired from teaching. I retired at the

minimum age. I was fifty-five, and I had taught here for twenty-one

years. I reached the point in the University Retirement System when

I could retire. Naturally, they take a percentage off your retirement

benefit if you only teach twenty years.

BD: But you retired so that you would have more

time for composing?

Binkerd: I retired so that I would have all my

time for it. That was in 1971, so I got a big stretch of time that’s

been absolutely my own.

BD: I trust you’ve made good use of it.

Binkerd: Oh, yes.

BD: Are most of the pieces that you compose on

commission?

Binkerd: Most are, yes.

BD: When you get commissions, how do you decide

if you will accept them, or postpone them, or reject them?

Binkerd: The first thing is how much money is

involved, and the second one if it is a project that I feel I am capable

of doing. Nobody could commission me to write an opera, or a band

piece. I wouldn’t know how to go about it. I’ve never had

any experience in those, and at my age, I would never agree to write a

symphony for anybody. That’s passed. I wrote four and that’s

enough. I couldn’t do it again.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] You and Brahms?

Binkerd: [Laughs] Brahms was 67 when he

died. I’m 72 now.

BD: When you’re writing a piece of music, are

you always in control of the pencil, or are there times when that pencil

is really in control of your hand?

Binkerd: That’s something that is more applicable

to a poet or a novelist than a composer. There are so many slips

between the cup and the lip in composition that you’re constantly changing

— at least I am

— from writing at a desk, which is all

done mentally, and consulting the piano, where the fingers are very much

involved. Perhaps it would be best to say that anything that comes

extraneously at me, comes while I’m at the piano.

BD: But once you start writing it down, I assume

that you tinker with it?

Binkerd: Oh, my goodness, yes! That’s all

it is — tinkering.

BD: Then how do you know when you’ve tinkered

the right amount, and you must go on?

Binkerd: [Laughs] It takes a lot of time,

and I just stay with it. It does take a lot of rewriting. One

of the hard lessons I learned from novelists is that a novel is not written

until it’s been revised, and recopied, and rewritten maybe twice or maybe

three times, and maybe more. That’s a terrible burden to take on if

you’re writing a symphony. You finish and you say now you’ll rewrite

it. It’s just a labor I can’t conceive of anymore.

BD: Did you often revise after hearing the piece?

Binkerd: Oh yes, always.

BD: Then are there a number of early versions

of pieces which are still around?

Binkerd: Well, I try to get rid of them, but

there are a few in various places.

BD: So what do we tell the future historians

who want to play your Urtext of a work?

Binkerd: Pretty much the printed versions are

what I would like. I finally got them to a place where they were

as right as I could make them.

* * *

* *

BD: Do you also do some conducting?

Binkerd: No. I did some when I was in college

but I have never been active. I’ve had church choirs and things like

that, but I don’t consider myself in any respect as a conductor.

BD: I just wondered how much you got involved

in the performance of your work.

Binkerd: I’m a pianist, so I’ve done quite a

bit of that.

BD: Are you the ideal interpreter of your piano

music?

Binkerd: In a way I am, even though I don’t have

the technique anymore that I used to have. I don’t practice at all,

so it’s largely gone. But without any kind of egoism, I could say

that I play in the way that I think they should be. [Laughs]

BD: Are there ever times when performers will

find things in your scores that you didn’t know you had hidden there?

Binkerd: That’s bound to be true, yes.

I don’t know if I’d hidden them there, but there are things that have

hidden themselves, and they show up sometimes when a performer learns

a piece, and gets familiar with it, and plays it with some kind of understanding.

If I ever knew they were there, I’d forgotten about them, and that does

happen all the time.

BD: Have you basically been pleased with the

performances you’ve heard of your music over the years?

Binkerd: Oh, yes! Just this past Sunday,

I went to a concert of my music in a little town you’ve never heard of,

Marinette, Wisconsin [about an hour North of Green Bay], and it was

one of the greatest concerts I’ve ever attended as far as the ability of

performers. It was absolutely incredible.

BD: The technical ability was very high.

Was the musical ability also high?

Binkerd: Oh yes, I should say so. Two young

people from Minneapolis did a performance of a violin sonata of mine. They

came over to Marinette and played, and it will never be played that well

again, I guarantee it. Never.

BD: Is that something you would hope to get a

good copy of the tape, and maybe license it for a recording?

Binkerd: [He laughs] I would like to, and I’ve

talked to them about it. When they go to Minneapolis, they said they’ll

definitely find a place and record it. Then we will see what we’ve

got. It’s hard to find a studio that’s well equipped, and also has

a wonderful piano in it.

BD: I asked you about performances, but have

you basically been pleased with the recordings that have been made, because

they have more general distribution?

Binkerd: Not entirely, no. There are two

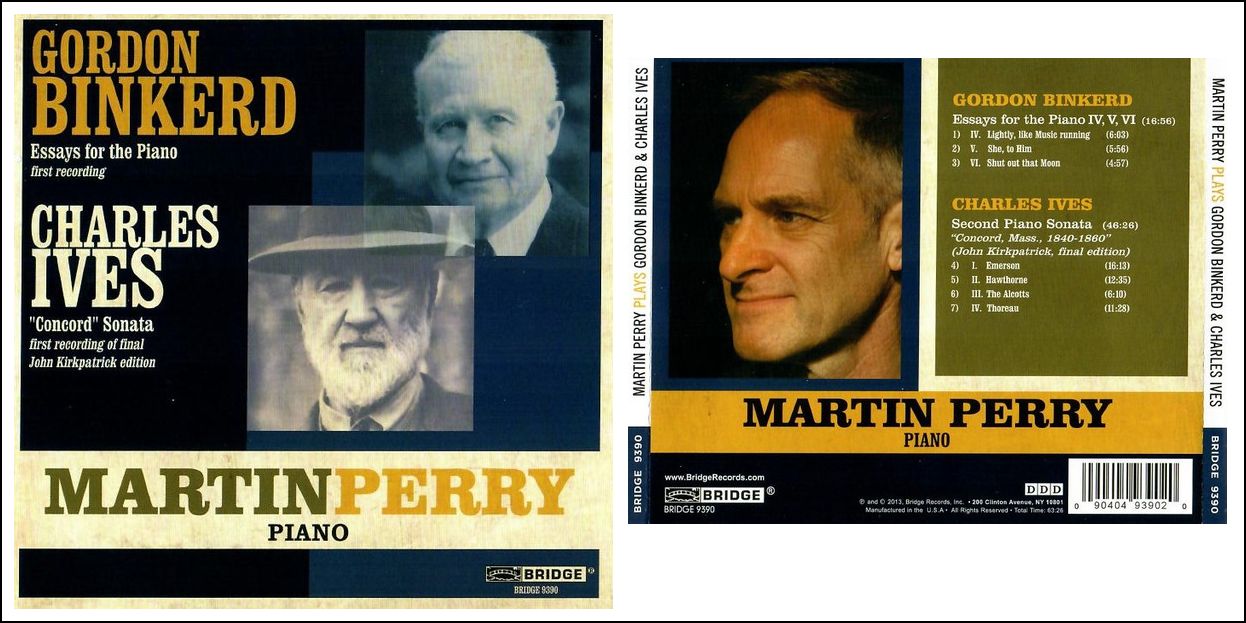

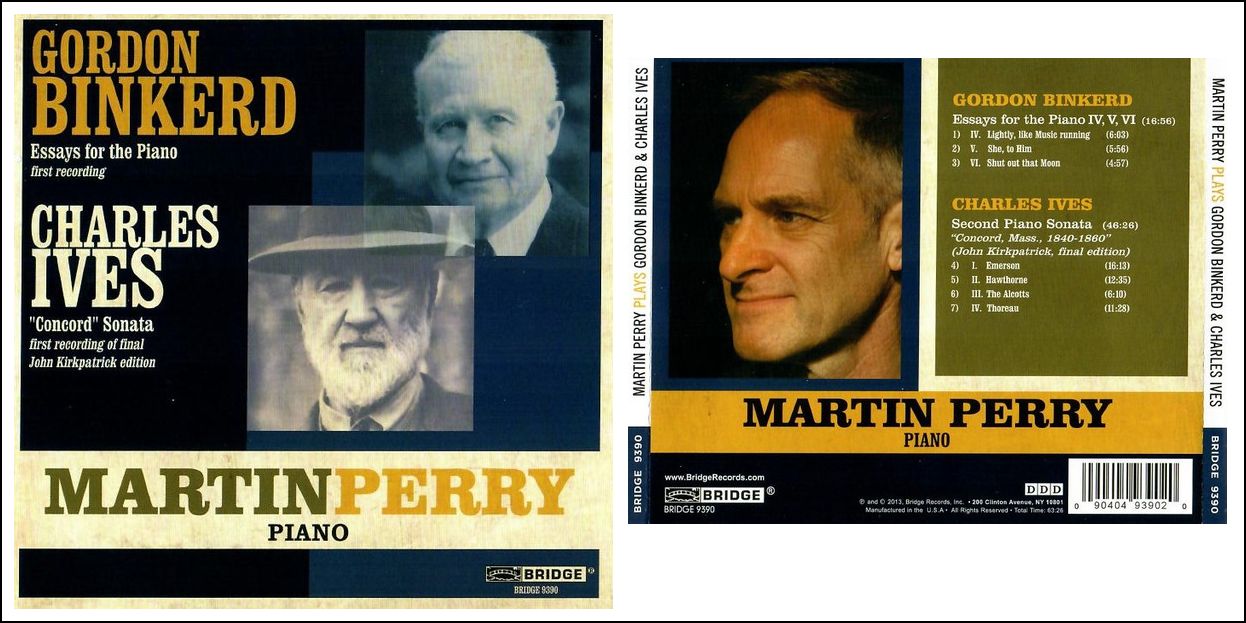

recordings that are unbeatable —

the Piano Sonata [shown at

right], and the Cello Sonata [shown below-left]. Those

are on CRI. The Piano Sonata was made by a colleague of mine,

pianist Stanley Fletcher, right here in our auditorium on our own recording

set-up. We went to New York to do this at the invitation of CRI,

and Stanley just couldn’t find a piano that suited him. We did it

in Steinway Hall, and he had higher standards than I do, and he just couldn’t

find a piano that did what he wanted to do on it. So, we came back

here and did it all over again, and it is just superb! It is the

last word.

BD: You should be grateful that he has such high

standards. [Vis-à-vis the recording shown at right, see my

interviews with Ernst Bacon,

and Menahem Pressler.]

Binkerd: I should say! I’m grateful to

him in many, many ways.

BD: What about the Symphony No. 2, [shown

below-right] which is also on CRI? Are you pleased with that?

Binkerd: I’m pleased with that, yes. It

was made in Oslo by the conductor of the Honolulu Symphony, George Barati.

He did a very good job. It was done in difficult circumstances

there. The piece has three horns parts in it, and they’re all very

high. The second horn player in an orchestra is not accustomed to playing

high. It’s usually divided up that the 1st and 3rd play high, and

2nd and 4th play low. Barati wrote to me about the trouble he had.

They had very little time with the orchestra, and just one rehearsal.

It all happened early one Sunday morning. They had struggled, and they

couldn’t find an alto flute for the very prominent part in the second movement.

I got a cable from them, asking if I would agree to a saxophone playing

that solo.

BD: Did you agree or not?

Binkerd: No, I didn’t agree! [He laughs]

They eventually found an alto flute, but I can’t imagine a European

orchestra without access to an alto flute player or instrument.

Anyway, it’s still a very good performance of that piece.

BD: I’m glad you’re pleased with it. As

far as the horn part, did you write it specifically to be difficult,

or is that just the way it had to come out?

Binkerd: To tell you the truth, it never occurred

to me that the second horn was going to have problems.

BD: Maybe you should put a note in the score

that you need a 2nd horn player who can play up there.

Binkerd: [Much laughter] Lots of orchestras

have an Assistant First Horn, and they divide up the high parts so they

don’t bleed out their lips. Anyway, it was surprisingly good, I thought.

BD: There’s also a record of Sun Singer

that was made by the University of Illinois.

Binkerd: That’s not available anymore.

In fact, the piece is not available. I buried it.

BD: [Surprised] Why???

Binkerd: It was a first-ever writing for orchestra,

and it was something that I thought shouldn’t live.

BD: What are you going to say when I

dig up the recording of it [shown above!]?

Binkerd: You mean in an old library, or something?

Well, don’t judge me by it, that’s all I can say! On the other

hand, everybody here thought it was a wonderful piece, they really did.

BD: Then who is the best judge of whether a piece

is good — is it the composer,

or is the public?

Binkerd: I suppose it’s the conductor.

There was an extra-musical reason why this was popularized. There’s

a very large statue by Carl Milles (1875-1955) of Sun Singer in

Allerton Park [shown below], which is part of the university.

That helped to sell the piece, I think. Rafael Kubelík

did the performance. Then, he brought the University Symphony up

to Orchestra Hall in Chicago and gave a concert which included that piece.

So, he liked it.

BD: [Smiling] Well, there you are.

[With a gentle nudge] If Kubelík likes it, who are you to

say it’s no good???

Binkerd: Yes! [Laughs] So did

Bernie Goodman, who was our conductor here for many years. He took

the orchestra on a South American State Department tour all over the whole

continent down there, and he played that work every time. The disc

that was done here was done by him. I rewrote it partly when he went

down to South America, and it was better then. I still think that

it’s possible to get more out of that piece, but I just think that life is

not long enough. It’s very hard to go that far back in time and try

to rebuild something. Usually, you end up by wounding it more than

you are helping it.

BD: What about the Symphony No. 1 on Columbia

[shown above-left]?

Binkerd: That recording was not a very happy occasion.

The St. Louis Symphony had a director, Edouard van Remootel, and

he wasn’t the best by any means. It turned out better than I thought

it would, but our orchestra played that piece so much better than the

St. Louis Symphony did. There just wasn’t any comparison. At

any rate, it was recorded. I should say something about the recording

of the Second Symphony [shown at right]. A lot of the copies

were mis-labeled. That record has a symphony by Ulysses Kay on it, and this

symphony of mine. Lots of those labels got reversed, and all kinds

of people have their opinion of me based on Ulysses Kay’s piece. [Both

laugh]

BD: My copy is on a cassette, because the LP is no longer

available.

Binkerd: I guess things are passing out. I had

the greatest trouble getting a record player that plays through your system.

They’re just a think of the past. I’ve also got thousands of recordings

on reel-to-reel tapes, and I can’t find a real-to-real tape machine anymore.

I finally found one, but it was not easy, and it doesn’t have all the speeds

on it that my tapes need.

* * *

* *

BD: What advice do you have for young composers

coming along today?

Binkerd: [Thinks a moment] I guess I don’t

have any. I don’t know what I would say to a person who wanted that

for his life.

BD: Is there any chance that we have too many

aspiring young composers?

Binkerd: No, I don’t think so. I just think

that U.S. of A. is not the place where a person can become a composer

if he expects to exist on it. Many get involved with teaching, like

I did. So, composing becomes almost a hobby.

BD: [With trepidation] Are you optimistic

about the future of music?

Binkerd: No!

BD: [Somewhat shocked] Not at all???

Binkerd: Not terribly, no. Why... are you?

BD: Let’s say I’m hopeful. [Both laugh]

Binkerd: At least we can relish an awful lot of

good music from the past.

BD: Are there any pieces being written today

that come anywhere near the standard of the great works of the past?

Binkerd: Oh yes, certainly. When you say

‘today’, if you mean the Twentieth

Century, we have Hindemith, Bartók, Walter Piston...

BD: Are there any in the last twenty years?

Binkerd: I’m not really in a position to talk

about that. I sort of dropped out of everything. I don’t go

to concerts anymore. I’ve been up to these concerts that have been

given here in the Midwest in the last three or four years, but that’s about

it. I don’t ever go to New York. I don’t ever expect to see New

York again, and I never come to Chicago. I go to St. Louis once in

a while because I have a doctor there treating my eyes, but that’s about

it.

* * *

* *

BD: Let me ask you a philosophical question.

In music, where is the balance between an artistic achievement and an

entertainment value?

Binkerd: Music has to entertain on some level,

otherwise you’re not going to listen to it. We had

a terrible stretch of music in the pits, ever since Schoenberg unloaded

his twelve-tone system on us. We have had this long period of time

where music has not pleased anybody, and so there’s very little entertainment

value in that music. I just think practically all of it’s been a

waste of time, but I have had enough of it. People are now jumping

off the band wagon, and looking around for something that has some kind

of relationship to the human psyche. I think that’s a good sign.

I did it a long time ago.

BD: Then let me ask this... What do you

feel is the real purpose of music in society?

Binkerd: Everything has been dealt a body-blow

by television, and music probably more than any of them. That’s where

people go for their entertainment. Maybe they don’t in big cities,

but they do everyplace else, and what you get on television is what they

give you. There’s a certain amount on public television which is

worthy, and, of course, television sets are not the world’s greatest reproducers

of music, but they’re better than nothing. Recordings are probably

the answer. A person can buy a recording and play it themselves.

[Pauses a moment] I don’t know... I think the world is in terrible

shape, and music goes right along with it.

BD: So, there’s no hope at all? [Both laugh]

Binkerd: No, I don’t say that, but I don’t envy

a young person starting out on his mature life, reaching the age of twenty-one

or twenty-five, and deciding he’s going to be a composer. But maybe

I’m all wrong!

BD: You spent twenty years teaching. Did

you notice any great change in the students, either in their ability or

attitude over that time?

Binkerd: No, they are always very good students all

the time. If you are talking about composer students, I am thinking

more of performers. I don’t think one should expect to find compositional

talent just lying around too much. It’s a very specialized field,

and lots of people have only part of the picture. You can be a person

with a tremendous ear and no imagination. You can be a person with

tremendous imagination and have a terrible ear, or find out when it’s too

late that you didn’t learn how to play the piano, because it’s so important

for a composer to be able to play the piano. What eventually comes

up in an individual is always accidental. You just mix everything, and

whatever comes up can be wonderful, or it can be flawed somewhere. Everybody

has got some kind of flaw in their professional equipment. But there

are plenty of people in this country so as to get a few composers. We’ve

had some good ones.

BD: [Optimistically] So we are still getting

good ones?

Binkerd: Ah, I don’t know. Two things have

changed the way young people go into composition. One is jazz music,

which has become stronger and stronger in its influence, and the other

is movie scores. Sometimes they call them ‘sound tracks’. That’s

going to be a place where composers will find themselves going more and

more, especially if they happen to have the background of experience of

playing in a dance band, and knowing that kind of procedure.

BD: Are these good things, or just things?

Binkerd: I don’t why they shouldn’t be good.

Shostakovich was very proud of his film scores, and he had lots of them.

We never hear them, but he thought that was an important part of his output.

Prokofiev also. Film scores are perfectly valid, and worthwhile

to play.

BD: Did you do any film scores?

Binkerd: No, I never had any.

BD: Would you write some if you’re offered them?

Binkerd: [Laughs] No, I wouldn’t. You

have to learn the technique. Copland did some when he was young, but

I wonder if he would have done them if he began when he was twice the age

he was when he did them. That’s something you have to start early with...

as so many things are.

BD: Do you feel that you are part of a lineage

of composers?

Binkerd: Yes, I do. I’m very much anti-contemporary.

I find my connections all in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-centuries,

with a few in the twentieth. I know the older I get, the more conservative

I get, and happier I feel about it.

BD: Are there any of your students who have gone

on to make big careers in composing?

Binkerd: I don’t know that ‘big’ is the proper

word. I have had some composition students who have persisted, and

have done very well, but none that are household names. Several

are, however, very capable people, and good composers.

* * * *

*

BD: What do you expect of the audience that can comes

to hear a piece of your music?

Binkerd: [Thinks a moment] What do I expect?

BD: Or perhaps what do you hope?

Binkerd: I don’t think it’s a very fair situation.

When I go to hear a piece for the first time, I very often don’t get much

of an impression from it. It takes more than one time. I just

hope that they get something out of it. That’s about all I can hope

for. By and large, there is something that is picked up by the average

concert-goer. This concert that I had last Sunday was a tremendous

success, even if I do say it myself.

BD: It’s good to hear you say that your works

are successful.

Binkerd: Last year there was a very similar concert

at Steven’s Point, Wisconsin [in the center of the state], and it

also was tremendously successful with the audience. I was just delighted.

Wisconsin Public Radio taped the program, and it was heard all over

the state. That was nice. A couple of years earlier we had one

in Brookings, South Dakota [on the Eastern edge of the state, about four

hours west of Minneapolis]. I went to school in Mitchell, South

Dakota [about an hour and a half south-west of Brookings].

BD: One last question. Is composing fun?

Binkerd: No, I don’t think that’s an appropriate

word. It’s terribly rewarding, though.

BD: I assume that you are still working on various

pieces?

Binkerd: Oh, yes, although age does intrude.

There are very few composers who have gone into their 70s and are still

active. It slows things down, but I have lots of ideas, and lots of

things that I mean to do before I stop.

BD: Thank you for spending the time with me today. I

look forward to putting parts of the conversation on WNIB along with your

music.

Binkerd: It was very nice talking with you.

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on May 29, 1988.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1991 and 1997. This

transcription was made in 2022, and posted

on this website at that time. My

thanks to British soprano Una Barry for

her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted

on this website, click here. To

read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as

well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975

until its final moment as a classical station

in February of 2001. His interviews

have also appeared in various magazines and journals

since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on

WNUR-FM, as

well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You

are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a full list of his

guests. He would also like to call your attention

to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.