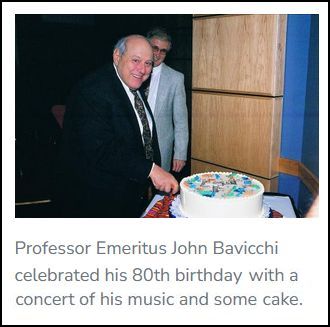

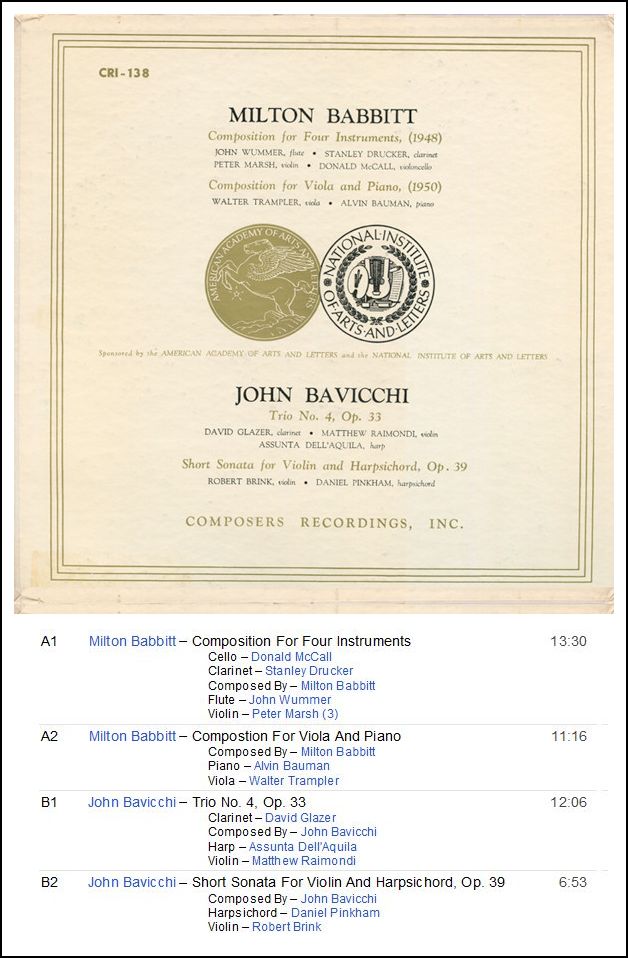

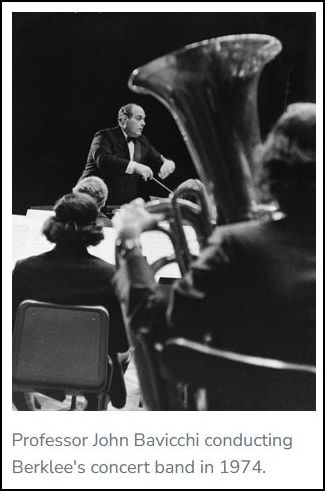

| John Alexander Bavicchi, born April 25, 1922, internationally renowned composer, conductor, and teacher, died quietly at home in Newton, MA on December 9, 2012 at age 90, following several months of deteriorating health. Mr. Bavicchi's initial training was as a civil engineer. A graduate of MIT with a degree in Civil Engineering, he saw combat action in the South Pacific during WW II as an officer in the United States Navy's Construction Battalion (Sea Bees). Returning to civilian life, he entered Boston's New England Conservatory of Music in 1948; after his graduation, he studied composition at the Harvard University Graduate School under Walter Piston, Archibald T. Davidson, and Otto Gombosi. As a young musician he played both the viola and the trombone. Mr.Bavicchi divided his time among composing, conducting, and teaching. Following various freelance teaching posts, he joined the faculty of Berklee College of Music in 1964 where he was made Professor Emeritus in 1997. He continued to work with students of composition until his death.  During the last six decades, John Bavicchi produced a diverse and

impressive catalog of more than 160 compositions in a variety of creative

instrumental and vocal combinations. He has been honored with awards

from The National Institute of Arts and Letters, ASCAP, the American

Symphony Orchestra League, and the Berklee College of Music. He has been

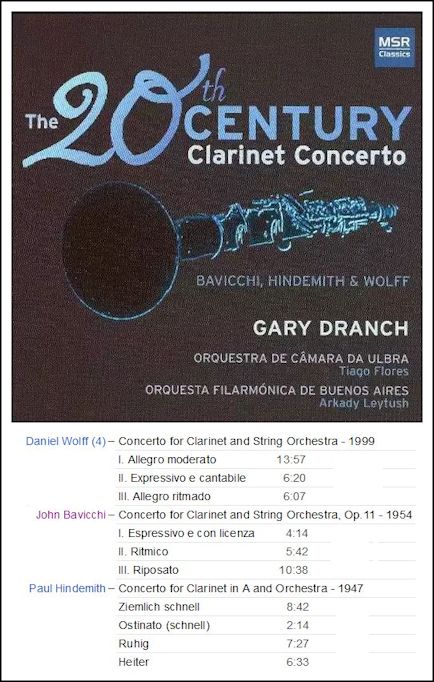

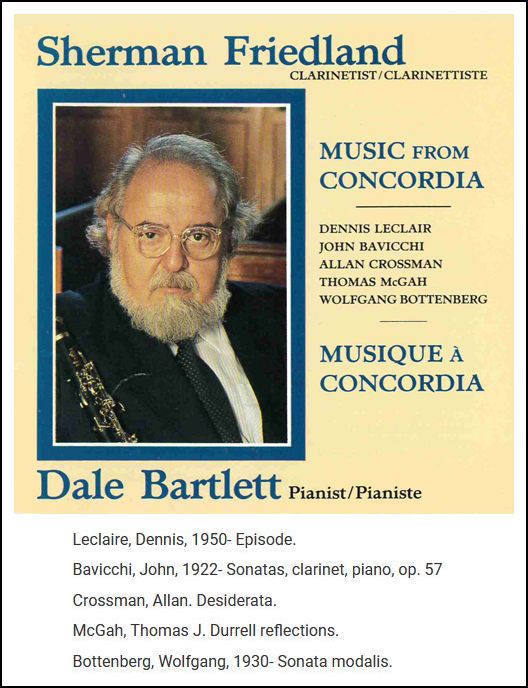

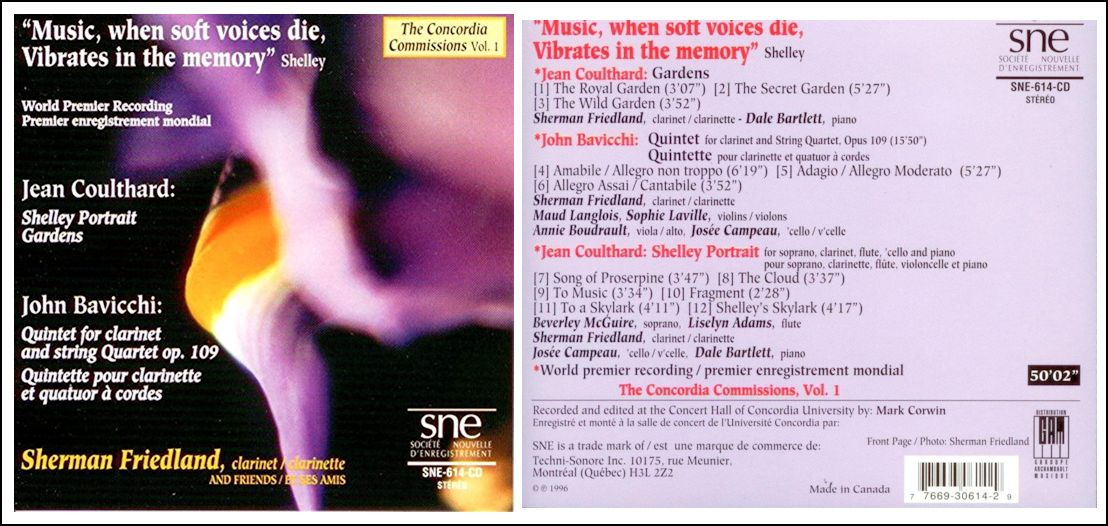

commissioned by, among others, the Harvard Musical Association, the Cecilia

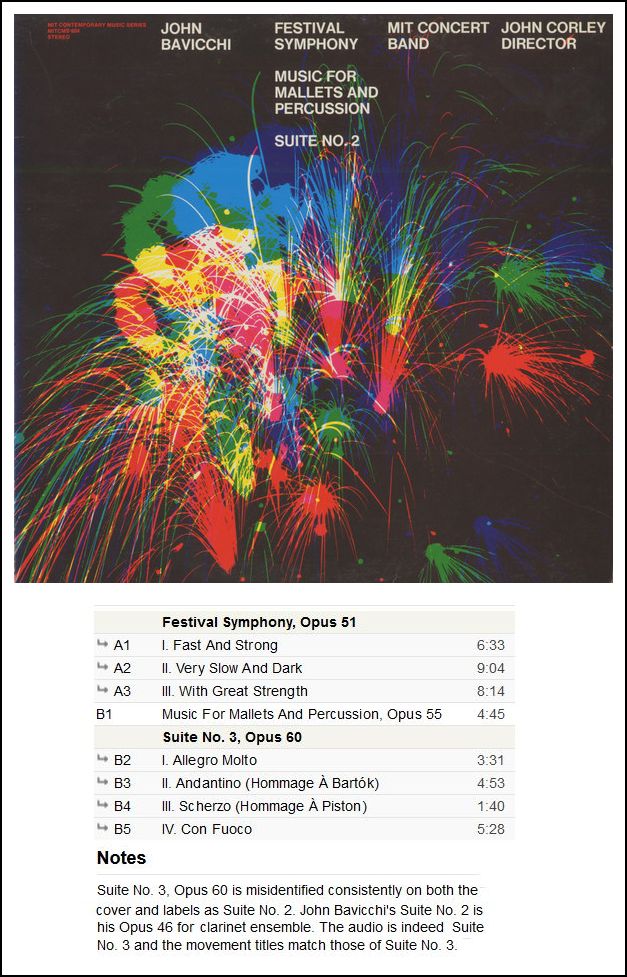

[choral] Society, the Welsh Arts Council, the MIT Concert Band, the Concord

Band, the Philharmonic Society of Arlington, and the Boston Civic Symphony.

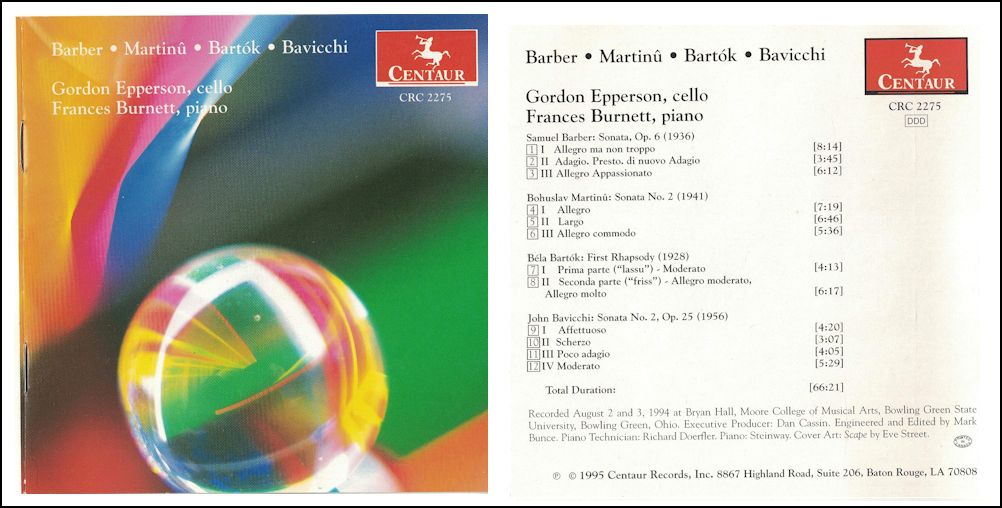

Much of Bavicchi's music has been published, most notably by the Oxford

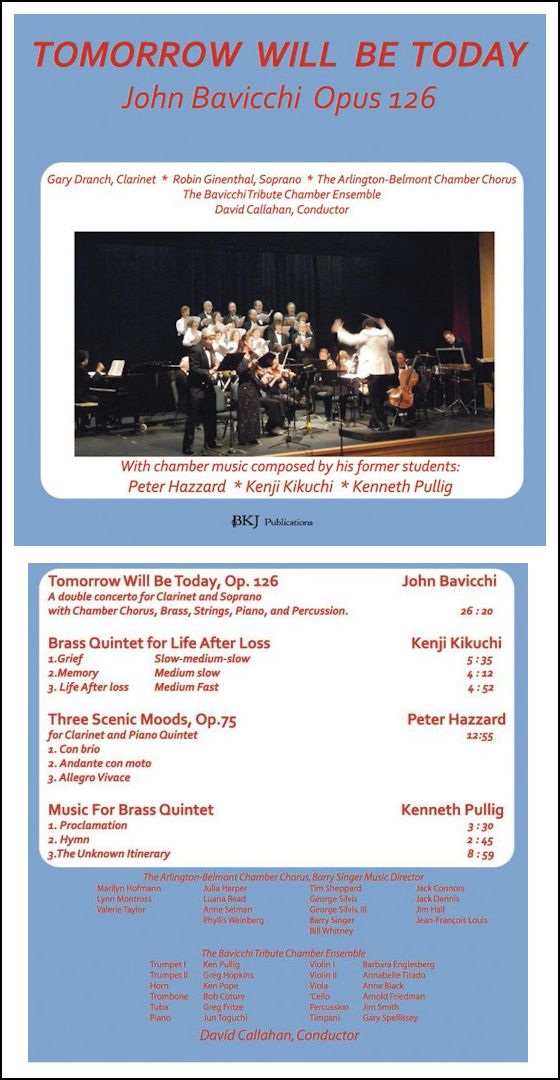

University Press. In 1955 he founded BKJ Publications, primarily as a

way to help young composers become eligible to join The American Society

of Composers Authors and Publishers (ASCAP.)

During the last six decades, John Bavicchi produced a diverse and

impressive catalog of more than 160 compositions in a variety of creative

instrumental and vocal combinations. He has been honored with awards

from The National Institute of Arts and Letters, ASCAP, the American

Symphony Orchestra League, and the Berklee College of Music. He has been

commissioned by, among others, the Harvard Musical Association, the Cecilia

[choral] Society, the Welsh Arts Council, the MIT Concert Band, the Concord

Band, the Philharmonic Society of Arlington, and the Boston Civic Symphony.

Much of Bavicchi's music has been published, most notably by the Oxford

University Press. In 1955 he founded BKJ Publications, primarily as a

way to help young composers become eligible to join The American Society

of Composers Authors and Publishers (ASCAP.) Mr. Bavicchi's music is performed internationally and a chamber music group in Birmingham, England named themselves The Bavicchi Ensemble in his honor. To say that Mr. Bavicchi was a fixture in the Boston music scene would be an understatement. Prior to his appointment to the faculty at Berklee College of Music in 1964, he taught at the Rivers School in Weston, MA and was also a regular lecturer at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education for many years. With his longtime friend, conductor and brass man John Corley, he founded Astor Concerts and, with Corley and Robert King, the Boston Brass Ensemble in 1953. He held a number of conducting posts over the years including the Sharon Orchestra, the Philharmonic Society of Arlington Orchestra and Chorus, the Belmont Chorus, and the Arlington-Belmont Chamber Chorus, of which he was the founder. He was a member of ASCAP and the American Symphony Orchestra League. An active stamp collector and member of the American Philatelic Society, he specialized in pre-cancelled U.S. stamps. He was also an avid sports fan, particularly fond of his New England Patriots. He bought season tickets in 1960 when the team (then called the Boston Patriots) was created, and he attended home games until the mid-2000s when he could no longer travel to the stadium. He tracked their statistics game by game and could quote even the second- and third-string players' vital stats. He virtually never failed to attend or view a game in the Patriots' history. Mr. Bavicchi was a true Renaissance Man. He loved fine art, read avidly and was knowledgeable in countless fields, and was a gourmet and connoisseur of spirits and fine wines. But above all, teaching was the part of his professional life that gave him the most satisfaction. He was influential in the development of hundreds of young composers, many of whom had little or no experience with classical music until they met him. He was a lifelong friend and inspiring and loyal mentor to generations of musicians. Those who have heard and performed John's music know that his pieces are distinctly challenging. When asked about this, John referenced a comment in a Boston Transcript review of Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto #1 when it was first performed: "Could anyone learn to love such music?" Regarding the difficulty characteristic of contemporary music, John said, "How it seems is largely dependent on the perception of the listener. I sometimes write according to the ability of the players for whom I am writing. But always my music is the compilation of everything I know -- beautiful, powerful, abstract, driving, placid, impassioned -- at the highest level I can manage." Bavicchi is survived by his life partner of more than 60 years, Beverly Lewis of Newton, by his daughter, Janet Bavicchi of New London, New Hampshire, by her mother, Dorothy Bavicchi of Brookline, MA, and by his brother Robert Iafolla, of Rye, New Hampshire. Donations can be made to the Lewis/Bavicchi Endowed Fund, Berklee College of Music, Attention: Marjorie O'Malley, 1140 Boylston Street, Boston, MA 02215 or to the Bavicchi Fund, Philharmonic Society of Arlington, c/o Christine Bird, 995 Mass Avenue, #305, Arlington, MA 02476, both of which support aspiring young composers. Online guestbook at www.gfdoherty. com. Â George F. Doherty & Sons Wellesley 781-235-4100 == Text (only) from the Boston Globe

(with slight changes)

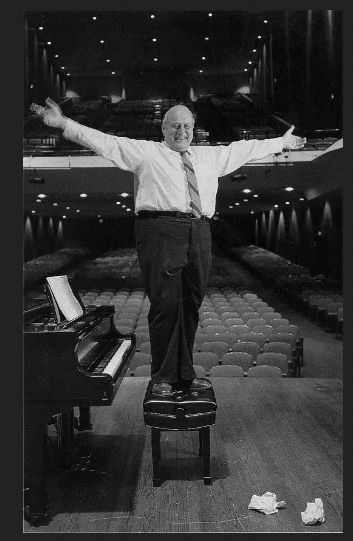

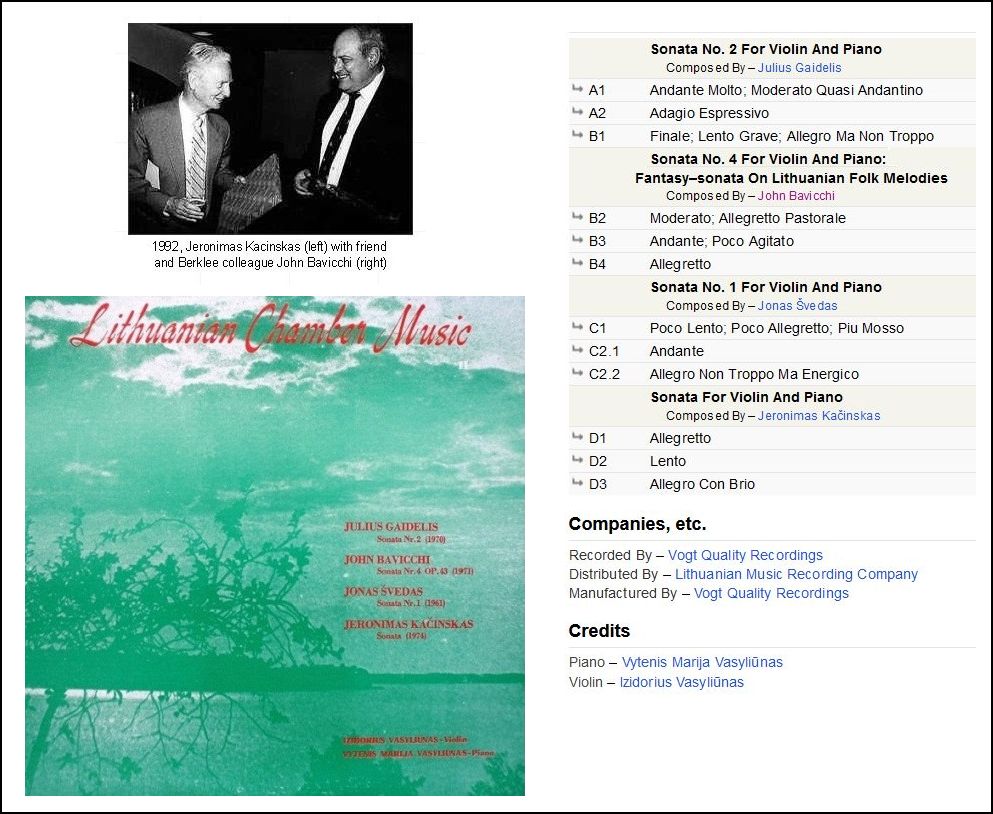

== Photo from Faculty Notes of Berklee College of Music |

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 24, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB three months later, and again in 1992, and 1997; and on WNUR in 2006, and 2013 . This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.