|

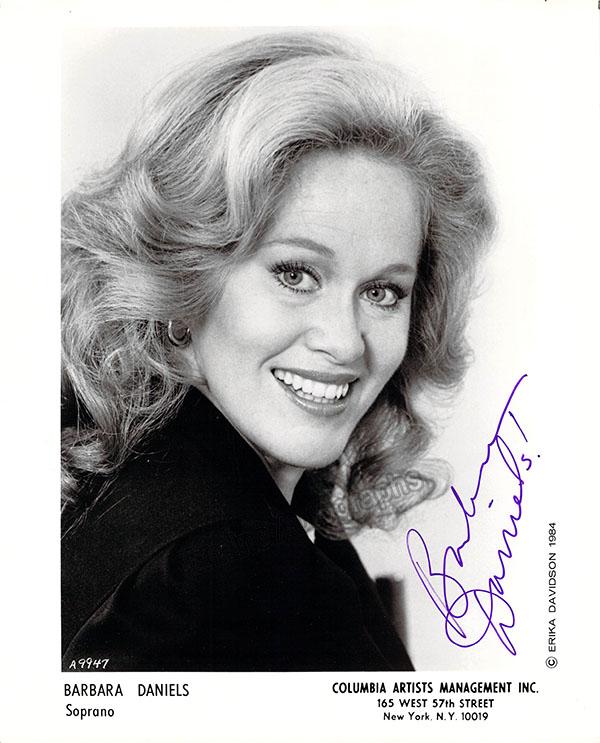

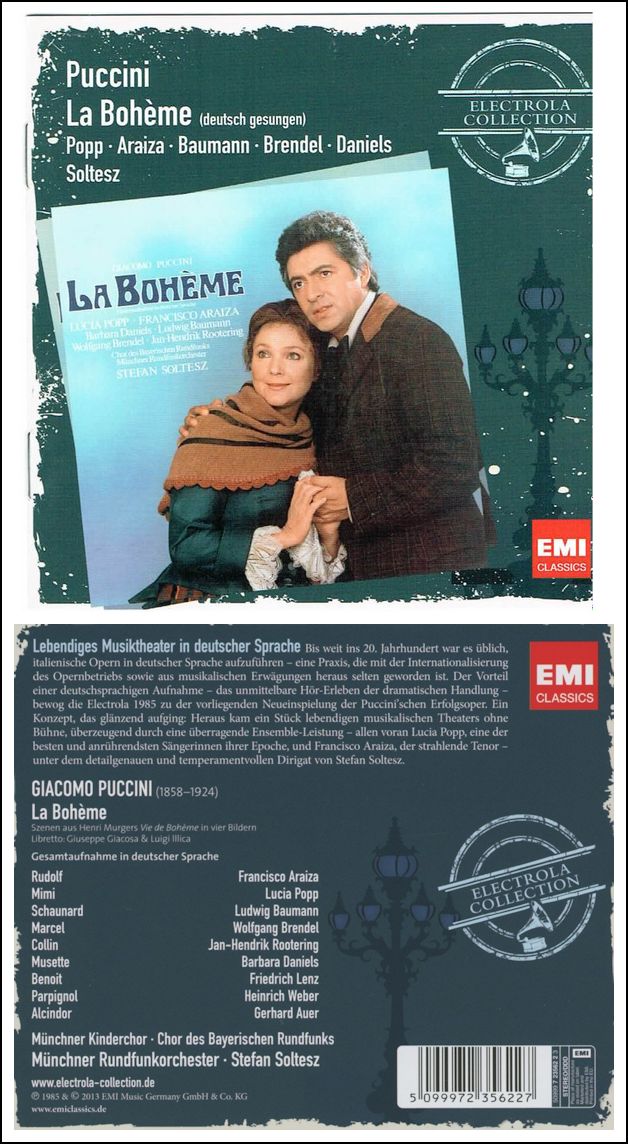

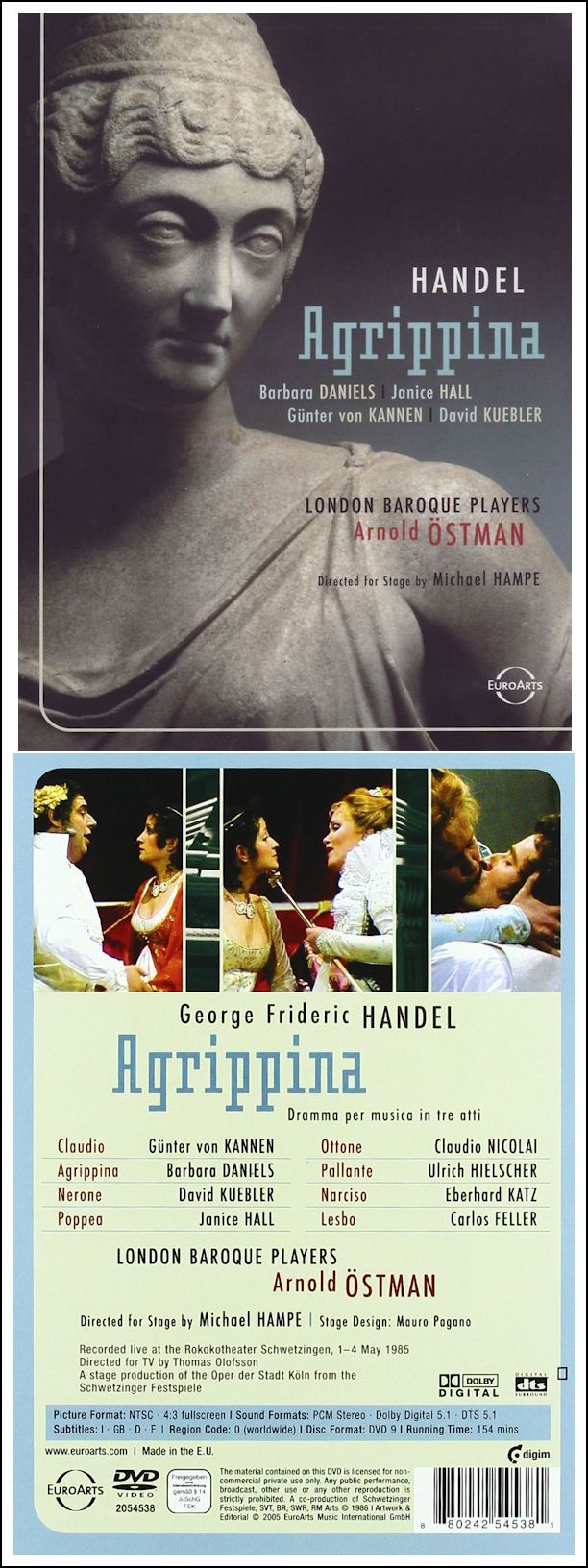

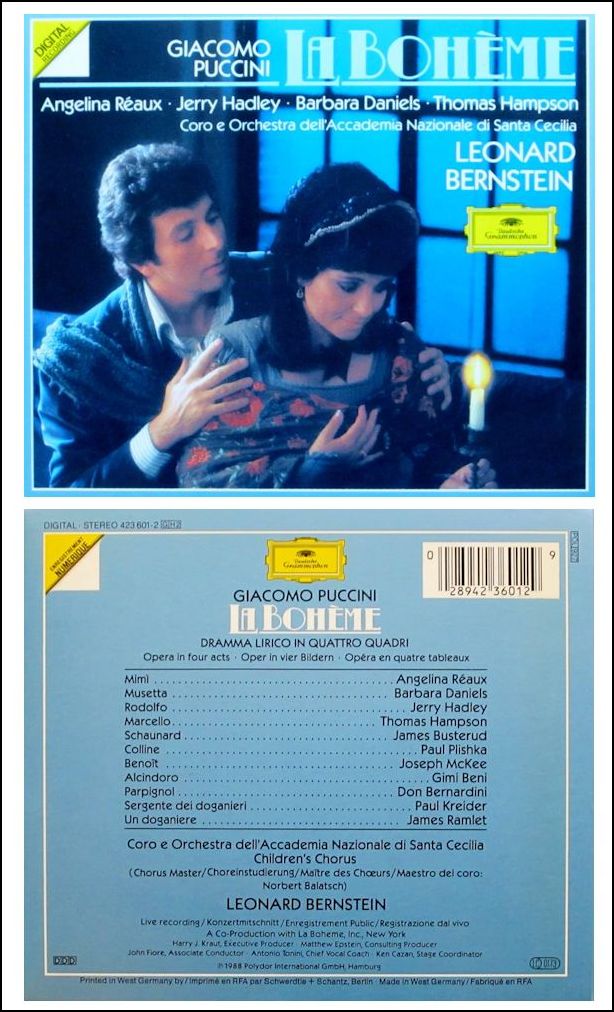

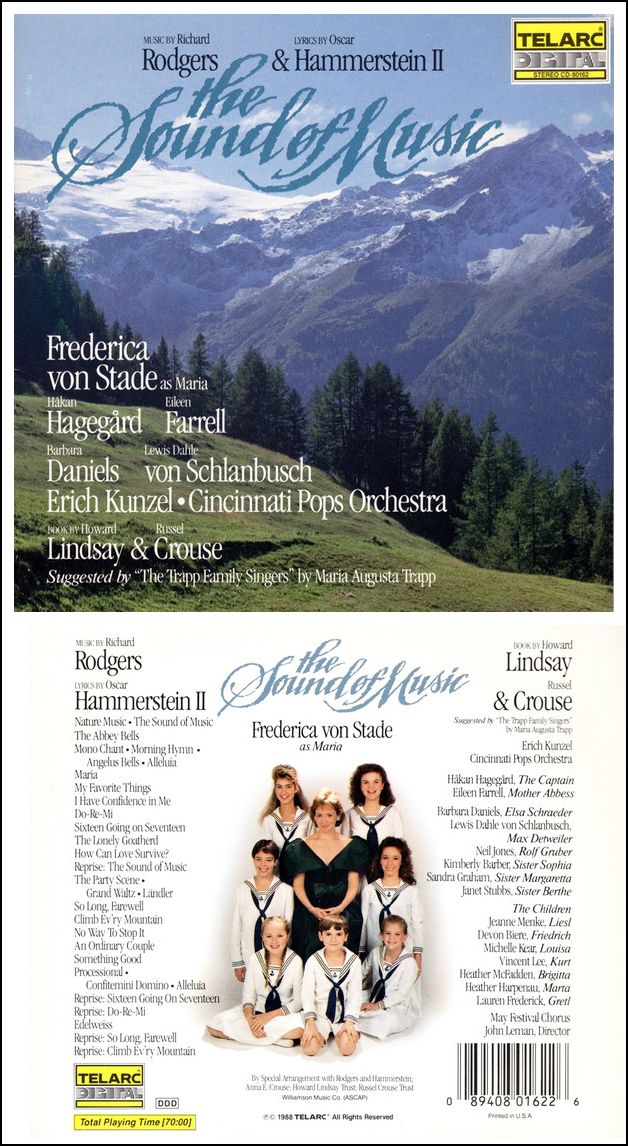

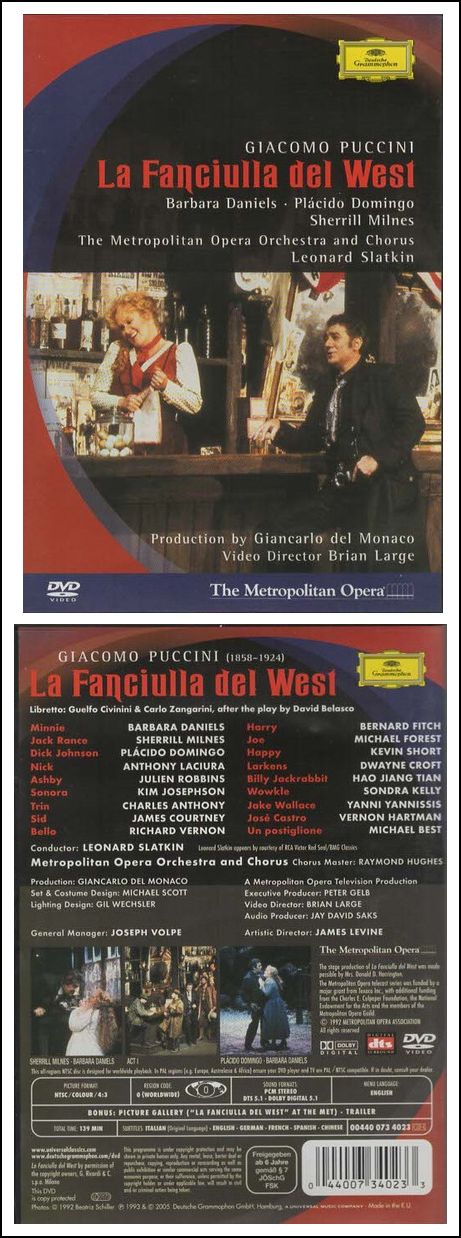

Barbara Daniels (born May 7, 1946) is an American operatic soprano. Born in Newark, Ohio, Daniels studied music at the University of Cincinnati – College-Conservatory of Music. Among her roles there was Diana in the American premiere of Francesco Cavalli's La Calisto in April 1972. Her professional debut came the following year with West Palm Beach Opera, where she sang Susanna in Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro. From 1974 until 1976 she was on the roster of the Tyrolean State Theatre, singing such roles as Fiordiligi in Mozart's Così fan tutte and the title role of Verdi's La traviata. From 1976 to 1978 she was a member of the Staatstheater Kassel, where her repertory grew to incorporate Liù in Puccini's Turandot, the title role in Massenet's Manon, and Zdenka in Arabella by Richard Strauss. She also participated in performances of Unter dem Milchwald by Walter Steffens. In 1978 she moved to the Cologne Opera, where she would remain until 1982. There she sang the title role in Flotow's Martha, Micaëla in Bizet's Carmen, Musetta in Puccini's La bohème, and Alice Ford in Verdi's Falstaff. It was during this time that she made debuts at the Royal Opera House (1978, as Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus by Johann Strauss) and San Francisco Opera (1980, as Zdenka). Her Metropolitan Opera debut, as Musetta, followed in 1983, where she would go on to perform 119 times. In earlier years, Daniels possessed a lyric voice, and her repertory encompassed such parts as Adèle in Rossini's Le comte Ory, the title roles in Handel's Agrippina and Puccini's Madama Butterfly, Mimì in La bohème, the title role in Smetana's The Bartered Bride, and Marguerite in Gounod's Faust. Later in her career her voice became more powerful and dramatic. In 1991 she performed Minnie in Puccini's La fanciulla del West at the Metropolitan Opera, and she added the title roles in Puccini's Tosca and Manon Lescaut, and the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss to her repertoire. She continued her career into the 1990s with Nedda in Leoncavallo's Pagliacci and Senta in Wagner's Der fliegende Holländer. She has also worked as a voice teacher, living in Innsbruck. |

James Lockhart was born on October 16, 1930, in Edinburgh and studied at the Royal College of Music. He worked as a répétiteur (singing coach) at the Städtische Bühnen Münster, Germany from 1955 to 1956. He was music director at Welsh National Opera from 1968 to 1972, and at the opera of the Staatstheater Kassel from 1972 to 1978 — the first British born person to hold that position with a German opera. He conducted a rare German outing for The Yeomen of the Guard in Kassel in October 1972. He was the Royal College of Music’s director of opera from 1986 to 1992. |

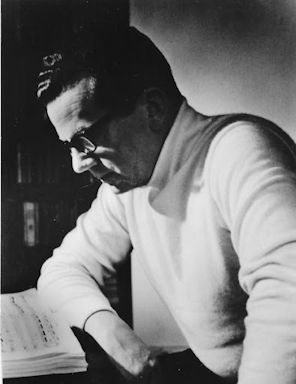

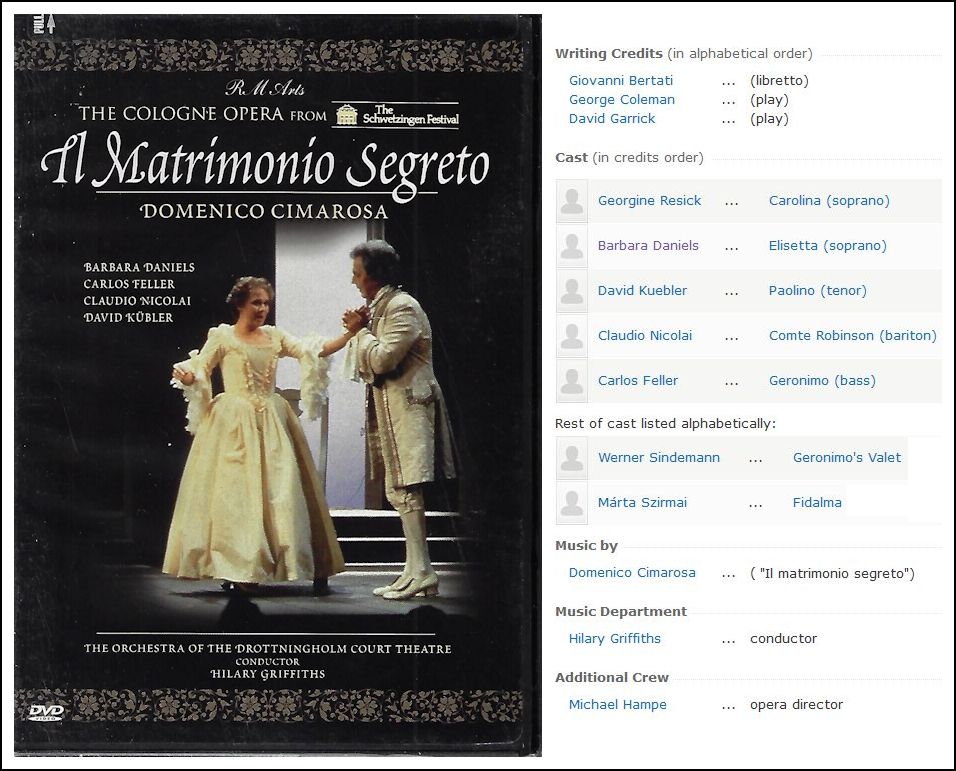

Michael Hampe (June 3, 1935 – November 18, 2022) was a German

theater and opera director, general manager (Intendant) and

actor. He developed from acting and directing

plays at German and Swiss theatres including the Bern Theater, to focus

on directing opera and managing opera houses, first at the Mannheim National

Theater, then the Cologne Opera from 1975, a position he held for 20

years. During his tenure, the Cologne Opera became one of the leading

opera houses in Europe. His productions of works by Richard Wagner and

Gioachino Rossini are remembered, as well as his engagement for the

operas of Benjamin Britten and Leos Janáček. His

1979 production of Cimarosa's Il matrimonio segreto became a

worldwide success with performances in London, Paris, Edinburgh, Venice,

Stockholm, Washington, Tokyo and Dresden, and was awarded international

prizes including the Olivier Award. [DVD with Daniels is shown below.]

He returned to Cologne in the 2015/16 season to direct Puccini's La

bohème, a season later Beethoven's Fidelio, and in the 2020/21 season Mozart's

Die Zauberflöte.

Michael Hampe (June 3, 1935 – November 18, 2022) was a German

theater and opera director, general manager (Intendant) and

actor. He developed from acting and directing

plays at German and Swiss theatres including the Bern Theater, to focus

on directing opera and managing opera houses, first at the Mannheim National

Theater, then the Cologne Opera from 1975, a position he held for 20

years. During his tenure, the Cologne Opera became one of the leading

opera houses in Europe. His productions of works by Richard Wagner and

Gioachino Rossini are remembered, as well as his engagement for the

operas of Benjamin Britten and Leos Janáček. His

1979 production of Cimarosa's Il matrimonio segreto became a

worldwide success with performances in London, Paris, Edinburgh, Venice,

Stockholm, Washington, Tokyo and Dresden, and was awarded international

prizes including the Olivier Award. [DVD with Daniels is shown below.]

He returned to Cologne in the 2015/16 season to direct Puccini's La

bohème, a season later Beethoven's Fidelio, and in the 2020/21 season Mozart's

Die Zauberflöte.

Hampe was on the board of directors of the Salzburg Festival from 1983 until 1990, where he was the stage director for productions, often in collaboration with the scenic designer Mauro Pagano. His productions included the world premiere of Henze's adaptation of Monteverdi's Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria in 1985, Don Giovanni conducted by Herbert von Karajan in 1987, Rossini's La Cenerentola conducted by Riccardo Chailly in 1988, and Le nozze di Figaro conducted by Bernard Haitink in 1991. Hampe served as a guest director at major opera houses and festivals. For The Royal Opera, London, he directed Andrea Chénier (1984), Rossini's The Barber of Seville (1985) and La Cenerentola (1990). Other organizations where he directed include La Scala in Milan, as well as in Paris, Munich, Athens, Stockholm, Helsinki, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Washington, Buenos Aires, Santiago de Chile, Sydney and Tokyo, and at festivals in Florence, Pesaro, Ravenna, Drottningholm, Edinburgh and Lucerne Festival. Many of his productions were recorded for television broadcast or made into films. The total number of his productions is more than 260 as of 2020. He was professor at the Hochschule für Musik und Tanz Köln since 1977, and after the reunification of Germany, the Dresden Music Festival for which he commissioned and directed world premieres. Hampe was also in demand as a theater construction expert, and was vice president of the German Theater Technology Society. He consulted for the buildings of the Opéra Bastille in Paris and the New National Theatre Tokyo, as well as renovation and modernization of older theaters.

|

|

Jean Périsson (July 6, 1924 in Arcachon – February 18, 2019) was a French conductor. A pupil of Jean

Fournet, he won the first prize at the Besançon conducting

competition in 1952. He was assistant to Igor Markevitch at the Salzburg

Mozarteum, and was chief conductor of the Strasbourg Radio Orchestra from

1955-56. He was music director for the city of Nice from 1956-65, giving

Wagner cycles (with artists from Bayreuth). He was a permanent conductor at the Paris Opera from 1965-69 and led an early French production of Káťa Kabanová at the Salle Favart. He conducted in San Francisco, Ankara and Beijing., where he was invited by the People’s Republic of China to hold a one-month position with China National Symphony (formerly Central Philharmonic Society) in May 1980. He later conducted and recorded Bizet’s Carmen with Central Opera Theatre of China in 1982. |

Barbara Daniels at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1984 Arabella (Zdenka) - with Te Kanawa, Wixell, Kunde, Langton, Mignon Dunn, Kraft; Pritchard, Decker 1986-87 [Opening Night] Magic Flute (3rd Lady) - with Araiza, Blegen, Nolen, Serra, Salminen, Stewart, Taylor, White; Slatkin, Everding La bohème (Musetta, Mimì [one performance]) - with Ricciarelli, Polozov/Araiza/Shicoff, Corbelli, Washington, Kreider, [Brown]; Tilson Thomas, Copley 1988-89 Falstaff (Alice Ford) - with Wixell, Sandra Walker, Horne, Corbelli, Hadley, Andreolli; Conlon, Ponnelle 1989-90 Fledermaus (Rosalinde) - with Allen/Otey, Bonney, Rosenshein/Lopez-Yanez, Howells, Nolen, Adams; Rudel, Chazalettes 1992-93 Bartered Bride (Mařenka) - with Rosenshein/Lehman, Rose, Kraft, Philip Kraus, Clark; Bartoletti/Sulich 1996-97 The Consul (Magda) - with McCauley, Cowen, Zilio; Richard Buckley, Falls Ardis Krainik Gala - with (among others) Manca di Nissa, Chernov, Marton, Vaness, Jóhannsson, Anderson, Sylvester, Hagegård, von Stade, Malfitano, Zajick, Cangelosi, Ramey, Domingo; Barenboim (piano) |

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on September 8, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1988 and 1996. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.