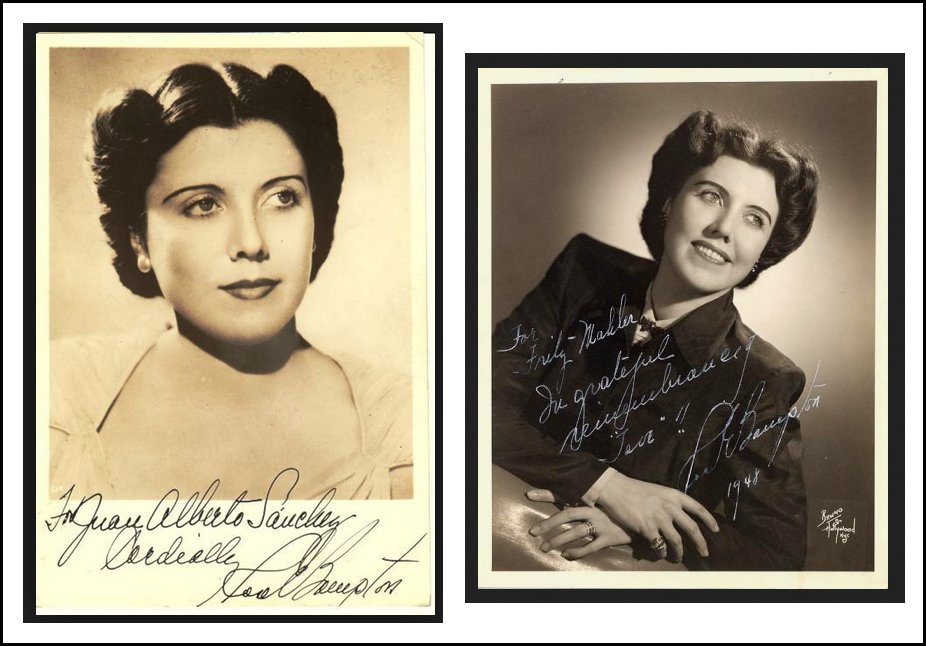

BD: One can’t get

much better than being recommended by the top performers themselves.

BD: One can’t get

much better than being recommended by the top performers themselves.

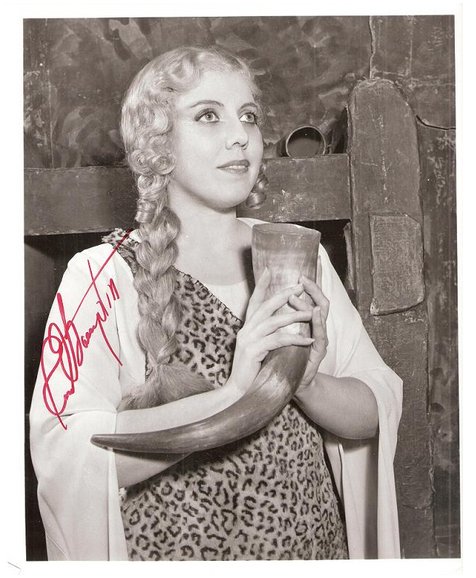

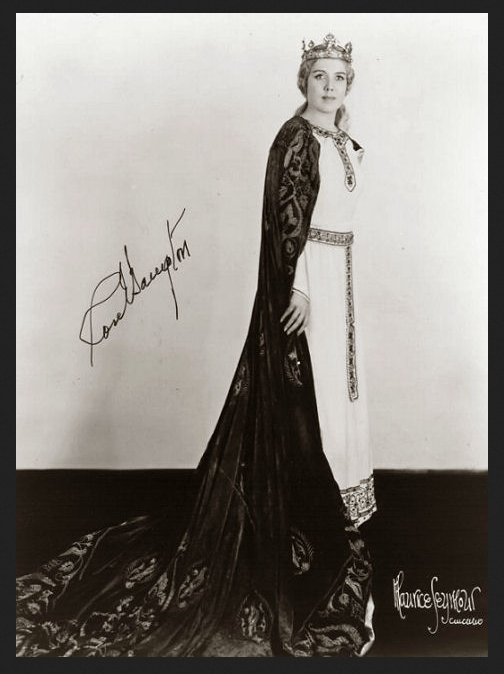

BD: Let us move on

to another Wagner role — Kundry [shown in photo at right].

BD: Let us move on

to another Wagner role — Kundry [shown in photo at right]. RB: It is.

It’s a wonderful role. In the third act she has to ride to

certain heights. I had a wonderful experience in this opera in

Buenos Aires. I had a wonderful director who had worked in the

straight theater, and he had been a fine actor and was a great stage

director. He also prepared our Daphne

there which was marvelous. His ideas of Lohengrin were marvelous and he

worked with me. When he got through, I told him I didn’t think I

could do all that he had shown me. It was all a mind-boggling

idea, but he told me that if I did one third of what he had told me it

would be a fine performance. He gave me so much to think about,

and made her into a real person. I think there is a danger

because she is so pure in every way. You have to be strong as

Elsa to compete with the character of Ortrud.

RB: It is.

It’s a wonderful role. In the third act she has to ride to

certain heights. I had a wonderful experience in this opera in

Buenos Aires. I had a wonderful director who had worked in the

straight theater, and he had been a fine actor and was a great stage

director. He also prepared our Daphne

there which was marvelous. His ideas of Lohengrin were marvelous and he

worked with me. When he got through, I told him I didn’t think I

could do all that he had shown me. It was all a mind-boggling

idea, but he told me that if I did one third of what he had told me it

would be a fine performance. He gave me so much to think about,

and made her into a real person. I think there is a danger

because she is so pure in every way. You have to be strong as

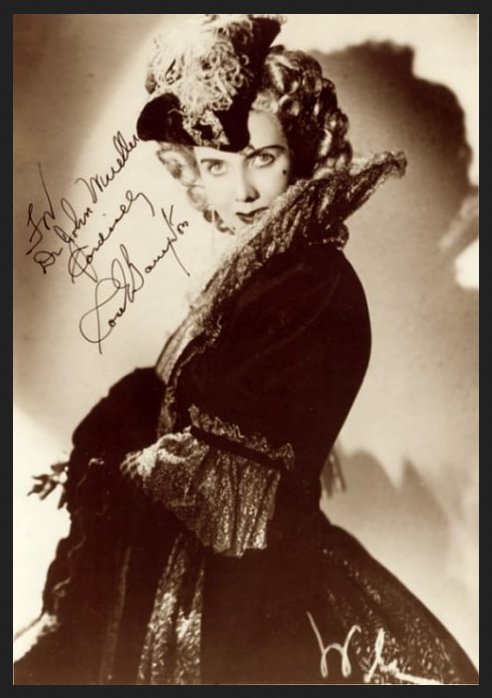

Elsa to compete with the character of Ortrud.  BD: You also sang Rosenkavalier [shown in photo at right]?

BD: You also sang Rosenkavalier [shown in photo at right]?

RB: Yes, I

do. I enjoy working with young people and watching their

growth. They’re interesting. I like to see the changes in

them as they mature, and observe how music changes them. As a

teacher you’re not only teaching them music, but you are hoping that

they will get something also as people to enrich their lives and to

raise their ambitions and their ideals in life. You’re not just

dealing with a voice. You have to deal with each one as a person,

hoping that they will grow mentally to understand all forms of

art. You try to help them become fine human beings. That’s

what we all hope for — at least that’s what I

hope for. I’m not sure we always accomplish it, but that’s our

aim.

RB: Yes, I

do. I enjoy working with young people and watching their

growth. They’re interesting. I like to see the changes in

them as they mature, and observe how music changes them. As a

teacher you’re not only teaching them music, but you are hoping that

they will get something also as people to enrich their lives and to

raise their ambitions and their ideals in life. You’re not just

dealing with a voice. You have to deal with each one as a person,

hoping that they will grow mentally to understand all forms of

art. You try to help them become fine human beings. That’s

what we all hope for — at least that’s what I

hope for. I’m not sure we always accomplish it, but that’s our

aim.|

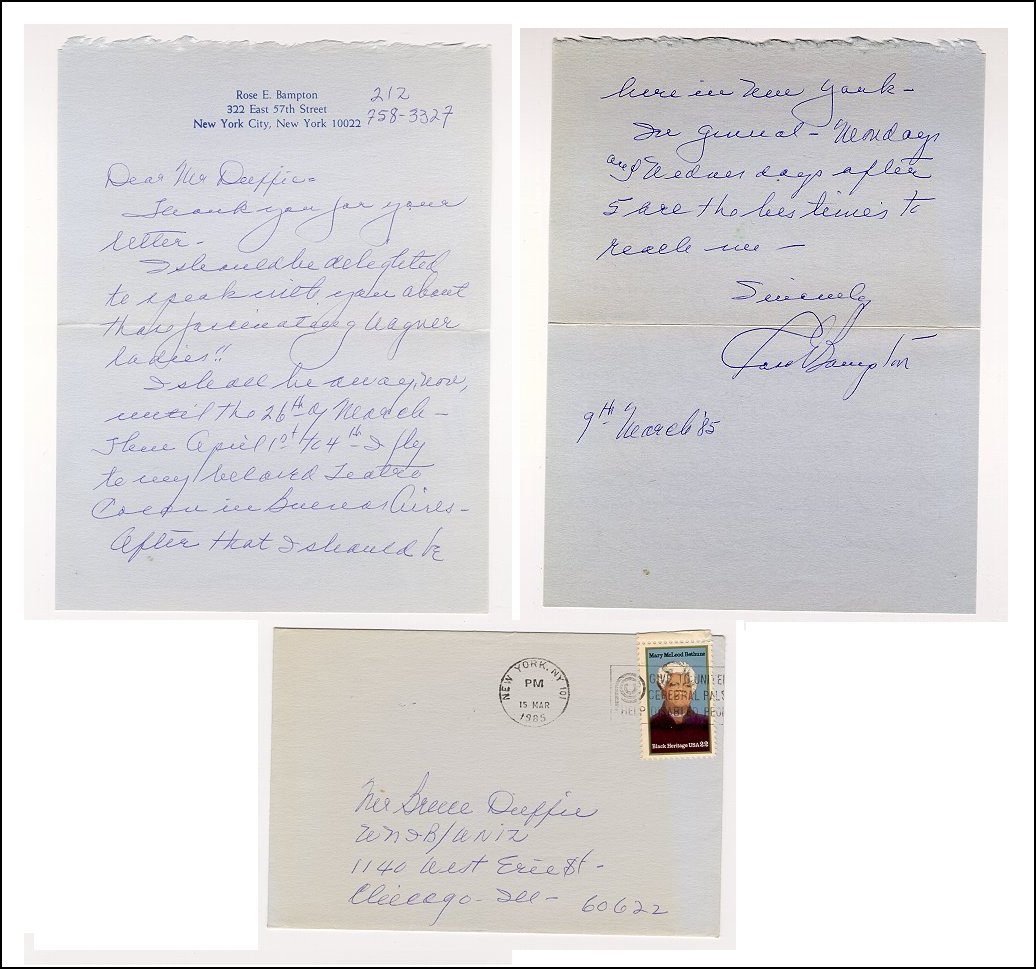

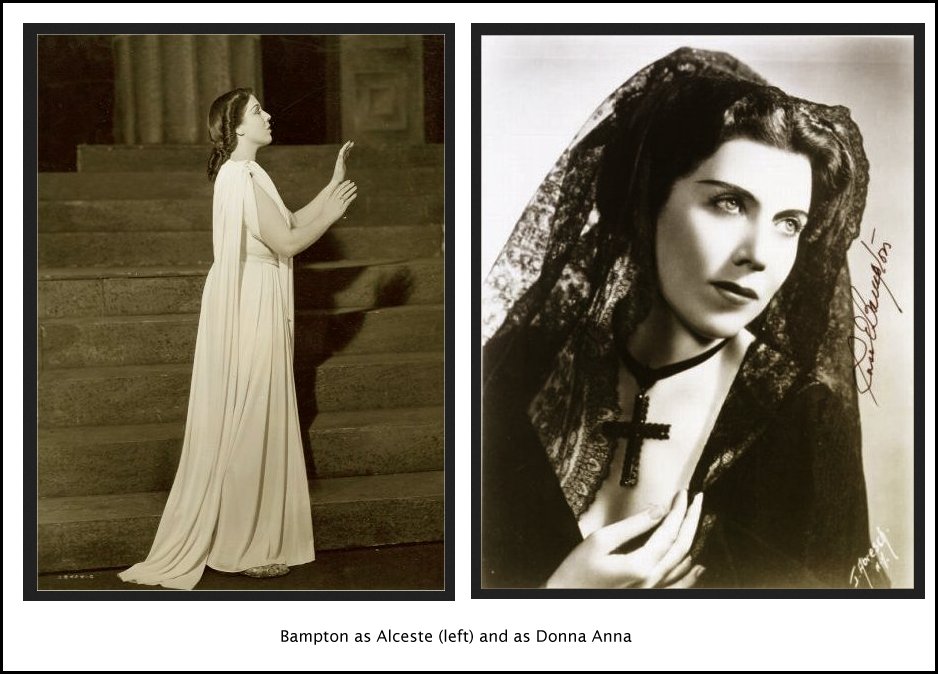

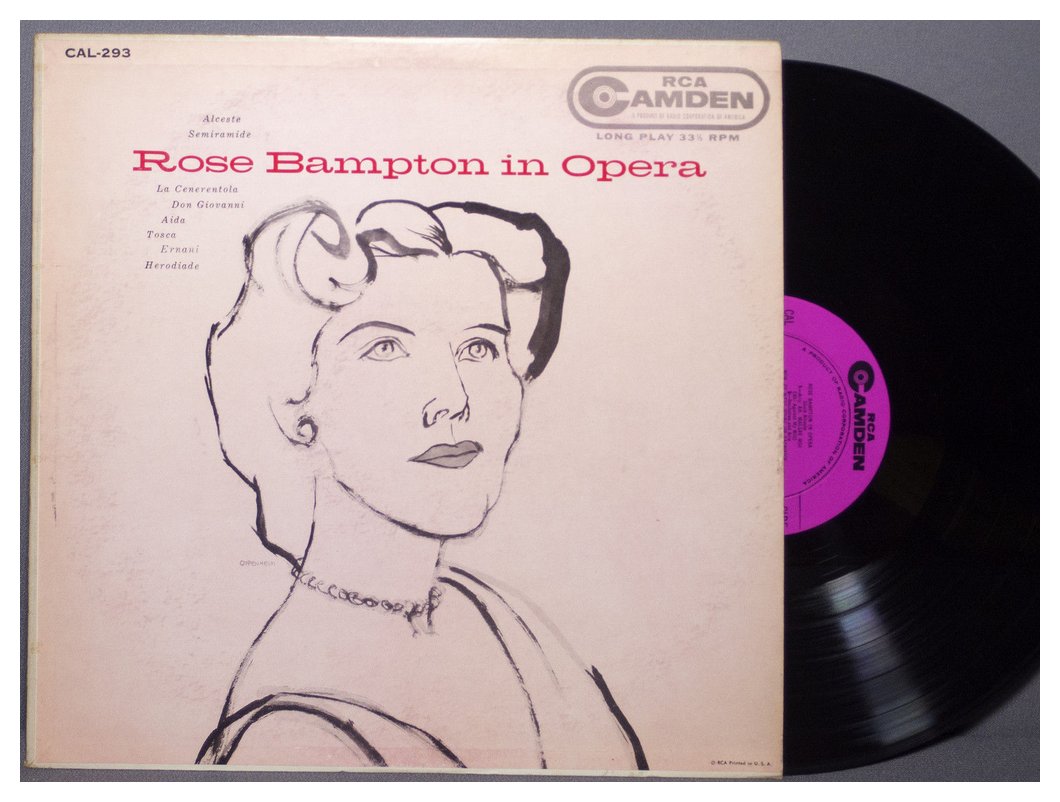

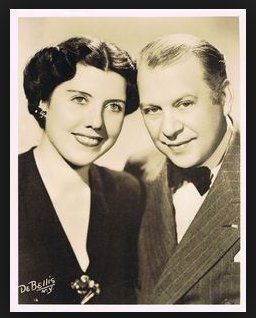

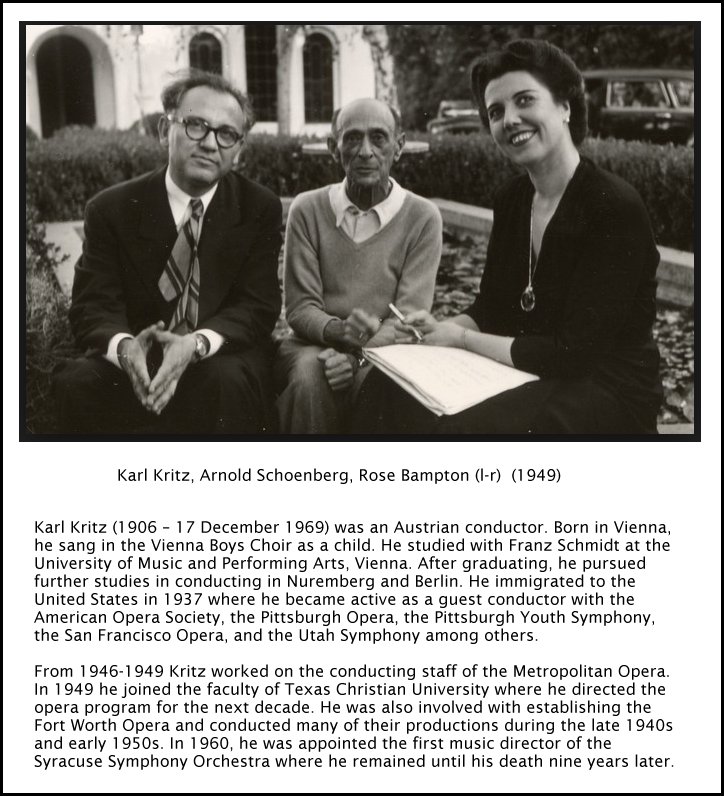

Rose Bampton, Versatile Met Singer, Dies at

99

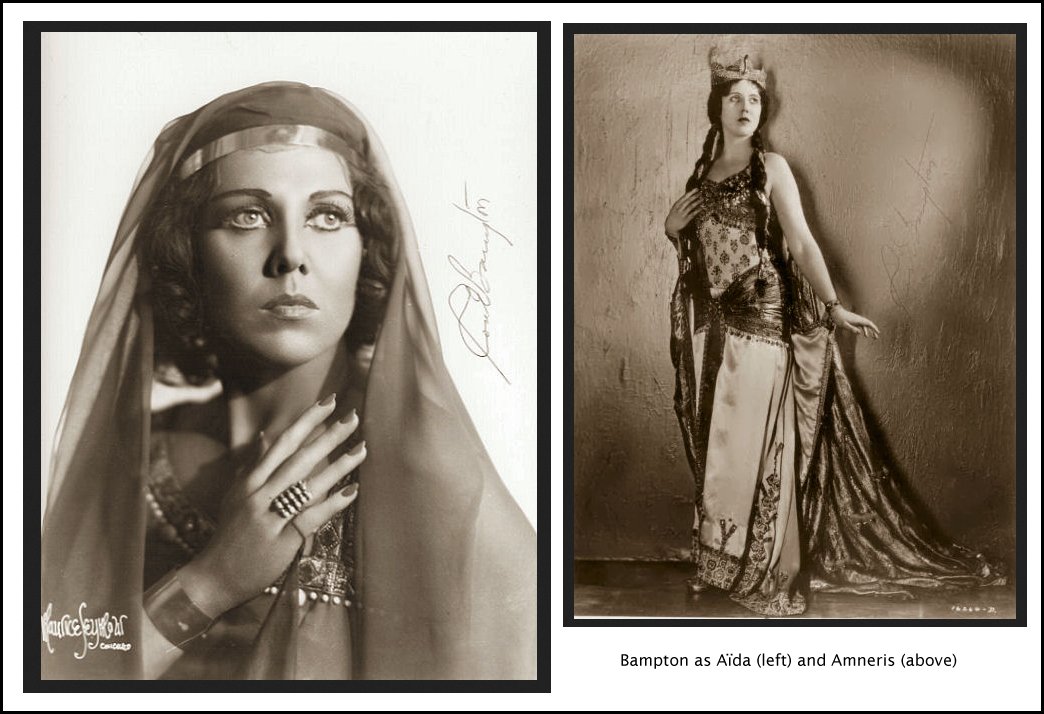

By ALLAN KOZINN, The New York Times AUG. 23, 2007 [Text Only; photos from other sources] Rose Bampton, an American opera singer who switched from mezzo-soprano to soprano and sang leading roles in both ranges at the Metropolitan Opera, died on Tuesday in Bryn Mawr, Pa. She was 99. Her death was announced by Peter Clark, a spokesman for the Metropolitan Opera. When Ms. Bampton made her Metropolitan Opera debut as Laura in “La Gioconda,” in November 1932, she had been singing professionally for only three years. But she had a considerable artistic arsenal that included a strong, finely polished voice and a trim, statuesque figure. During her years with the company — she retired in 1950 — her sound was generally regarded as attractive rather than thrilling, but she used it with an intelligence and interpretive flair that made her one of the most distinctive singers of her time. Ms. Bampton was born in Lakewood, Ohio, on Nov. 28, 1907, although during her career she sometimes gave her year of birth as 1908 or 1909. She spent her childhood in Buffalo and began her studies at Drake University, in Des Moines. Originally a soprano, she was pushed toward the mezzo-soprano repertory by her teachers after a bout with laryngitis, and when she made her debut at the Chautauqua Opera in 1929 it was in a mezzo-soprano role, Siébel, in Gounod’s “Faust.” In 1930 Ms. Bampton moved to Philadelphia, where she sang mezzo roles with the Philadelphia Grand Opera and enrolled at the Curtis Institute. One of Ms. Bampton’s fellow students at Curtis was the composer Samuel Barber, who enlisted her to sing in the New York premiere of his vocal chamber work “Dover Beach” in 1933. In Philadelphia Ms. Bampton also sang several times with Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra. A recording of one of those — the United States premiere of Schoenberg’s “Gurrelieder,” in which she sang the Wood-Dove — brought her to the attention of the Met.  Ms. Bampton’s roles during her first season included Amneris in Verdi’s “Aida” and small roles in “Parsifal,” “Die Walküre,” “Das Rheingold” and “Hansel und Gretel.” Other roles were added over the next few seasons. By the time she married Wilfrid Pelletier, a conductor at the Met, in 1937 (he died in 1982), she was feeling underemployed at the house, and decided to return to the soprano repertory. Ms. Bampton’s first appearance at the Met as a soprano was as Leonora in Verdi’s “Trovatore” on May 7, 1937. Her repertory expanded quickly over the next few years, to include Donna Anna in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni,” the title role in Gluck’s “Alceste,” and several Wagner roles: Sieglinde in “Die Walküre,” Elisabeth in “Tannhäuser,” Elsa in “Lohengrin” and Kundry in “Parsifal.” She also added the title role of “Aida” to her repertory, and in January 1940 she appeared at the Met as “Aida” one Saturday and as Amneris a week later.  In addition to singing at the Met, Ms. Bampton sang with companies in San Francisco and Chicago, as well as in Buenos Aires, where she sang several Strauss roles that she never performed in North America. She was also a recitalist and appeared regularly with the New York Philharmonic and other orchestras. Among her recordings that remain in print is a broadcast performance of “Fidelio,” in which she sang Leonore, with Arturo Toscanini conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra. There are no immediate survivors. |

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on May 6,

1985. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1993 and 1997.

This transcription was made and published in Wagner News in April of 1986.

It was slightly re-edited in 2016, the obituary and photos links were

added, and it was posted on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.